In a limestone cavern carved into the flanks of the Lesser Caucasus Mountains, archaeologists recently recovered an object no larger than a matchstick—yet carrying profound implications. Found amid layers of Mesolithic debris in Damjili Cave, Azerbaijan, this human figurine—crafted from sandstone with a striped belt and stylized coiffure—offers a rare glimpse into the symbolic world of hunter-gatherers teetering on the cusp of the Neolithic.

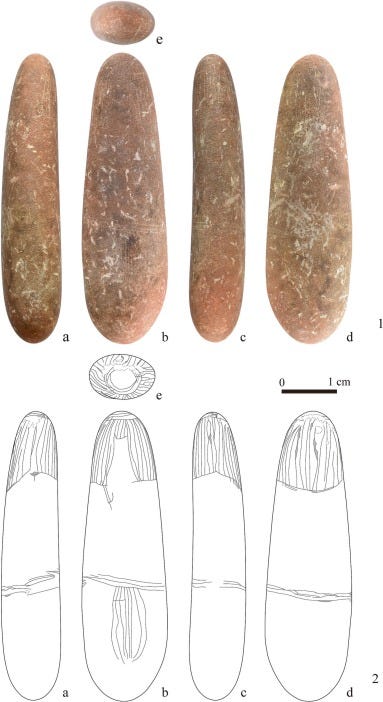

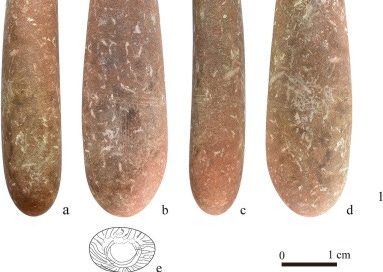

The object, just 51 mm in length and 15 mm wide, lacks facial features. It is faceless, but not formless. A neat hairstyle curls toward the back, and a carved belt wraps the torso, perhaps denoting identity, status, or gender—though the figurine’s sex remains debated. According to a collaborative report published by Japanese and Azerbaijani researchers in Archaeological Research in Asia1, this is the first such artifact known from Mesolithic layers in the South Caucasus. Its presence is stirring new conversations about ideology, identity, and artistic expression during a key turning point in Eurasian prehistory.

“We are seeing a rare symbolic artifact from a time and place where such expressions are nearly absent,” said Yutaka Nishiaki, lead author of the study and professor of prehistoric archaeology at the University of Tokyo. “It marks a conceptual shift, suggesting that the construction of human identity—beyond survival—was becoming increasingly important during the Mesolithic-Neolithic transition.”

A Region in Transition

Damjili Cave has long been known as a cultural palimpsest. Nestled in the Gazakh district of northwestern Azerbaijan, the cave preserves archaeological deposits that span over 100,000 years. But recent excavations, led by the Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences in collaboration with Japanese institutions, have targeted the transitional period between the Mesolithic and Neolithic—roughly 12,000 to 8,000 years ago.

This was an era of profound change in the South Caucasus. Climate shifts at the end of the Pleistocene transformed ecosystems. Mobile foraging bands began experimenting with food storage, semi-permanent dwellings, and new toolkits. Yet symbolic artifacts from this period in the region have been frustratingly rare.

That’s what makes the figurine from Damjili exceptional.

“This find plugs a symbolic hole in the Mesolithic archaeology of the Caucasus,” said Ulviyya Safarova, the Azerbaijani archaeologist who discovered the figurine during the 2023 field season. “We know these communities were innovating technologically, but now we can trace how their inner symbolic lives may have been changing, too.”

Figurines Beyond Fertility

Human figurines from prehistoric contexts often stir debates around meaning. In Paleolithic Europe, so-called "Venus figurines" have traditionally been interpreted as fertility symbols, matriarchal deities, or even Paleolithic pornography. But more recent scholarship urges caution, emphasizing local context and function over universal interpretation.

At Damjili, the figurine’s belt and hairstyle seem intentional, but no overt sexual features are present.

That hypothesis aligns with recent theories that see figurines not just as ritual objects but also as tools for negotiating emerging social complexity. As populations became more sedentary, competition for resources and space would have demanded new forms of group cohesion—identity became as important as survival.

Made of Sandstone, Shaped by Culture

The sandstone figurine underwent non-destructive imaging and geochemical analysis in Japanese laboratories, confirming its anthropogenic origin. Its stylized body contrasts sharply with utilitarian stone tools from the same layer, which include microliths and bladelets. While those tools spoke to subsistence, the figurine whispers of belief, memory, and personhood.

It is worth noting that sandstone is not native to the immediate cave environment, implying that the material—or the finished object—was brought in from elsewhere.

“This object was not incidental,” Nishiaki noted. “Its production, transport, and deposition required intention. That’s what makes it valuable as a marker of symbolic cognition.”

The figurine’s presence alongside other Mesolithic tools suggests it was part of everyday life rather than a one-off ceremonial deposit. In this sense, it may be closer to a personal amulet or social token than to later Neolithic fertility statues.

Reassessing the South Caucasus

The Damjili figurine joins a growing corpus of prehistoric portable art found across Eurasia, but it stands out for both its context and its age. In the Fertile Crescent and Anatolia, human figurines proliferate by the Neolithic, often in clay or limestone. But the South Caucasus has remained understudied, partly due to political factors and limited excavation seasons.

Finds like this suggest that symbolic life in the region was more robust than previously believed.

“The figurine compels us to think of Mesolithic people in the Caucasus not as passive foragers awaiting the Neolithic ‘package’ but as active participants in cultural innovation,” said Raven Garvey, an anthropologist not involved in the study. “The symbolic world was already blooming.”

Related Research

Here are some studies that provide valuable context to the Damjili Cave discovery:

Minaev, P. V., & Fedorov, V. A. (2023). Symbolic behavior during the Upper Paleolithic: Reassessing the role of portable art in early Eurasia. Quaternary International. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2023.06.002

Goring-Morris, A. N., & Belfer-Cohen, A. (2018). From the Epipaleolithic to the Neolithic in the Near East: Where is the evolution? Current Anthropology, 59(S18), S571–S584. https://doi.org/10.1086/699884

Soffer, O., Adovasio, J. M., & Hyland, D. C. (2000). The “Venus” figurines: Textiles, basketry, gender, and status in the Upper Paleolithic. Current Anthropology, 41(4), 511–537. https://doi.org/10.1086/317383

Bar-Yosef Mayer, D. E., Vandermeersch, B., & Bar-Yosef, O. (2009). Shells and ochre in Middle Paleolithic Qafzeh Cave, Israel: indications for modern behavior. Journal of Human Evolution, 56(3), 307–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.10.005

Nishiaki, Y., Safarova, U., Ikeyama, F., Satake, W., & Mammadov, Y. (2025). Human figurines in the Mesolithic-Neolithic transition of the South Caucasus: New evidence from the Damjili cave, Azerbaijan. Archaeological Research in Asia, 42(100611), 100611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ara.2025.100611

Share this post