For decades, archaeologists believed that technological development in Paleolithic East Asia followed a slow, relatively stagnant trajectory compared to the dynamic shifts seen in Europe and Africa. The discovery of a sophisticated stone tool tradition in southern China is now forcing a major reassessment of that assumption. Recent excavations at the Longtan site in southwest China have uncovered a complete Quina lithic toolkit—previously thought to be exclusive to European Neanderthals—dating back approximately 50,000 to 60,000 years ago. The presence of this distinctive technology so far from its previously known origins raises new questions about ancient human migrations, cultural exchange, and independent innovation.

What Is Quina Technology?

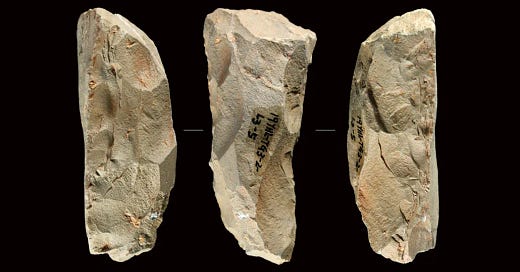

Quina technology is a specific way of shaping stone tools, best known from European Neanderthal sites such as La Quina in France, where it was first identified in 1953. The hallmark of this system is the Quina scraper—a thick, asymmetrical stone tool with a broad, sharp edge that shows clear signs of repeated use and resharpening. These tools were highly efficient for working hides, bones, and wood, making them valuable for mobile hunter-gatherer groups facing harsh environments.

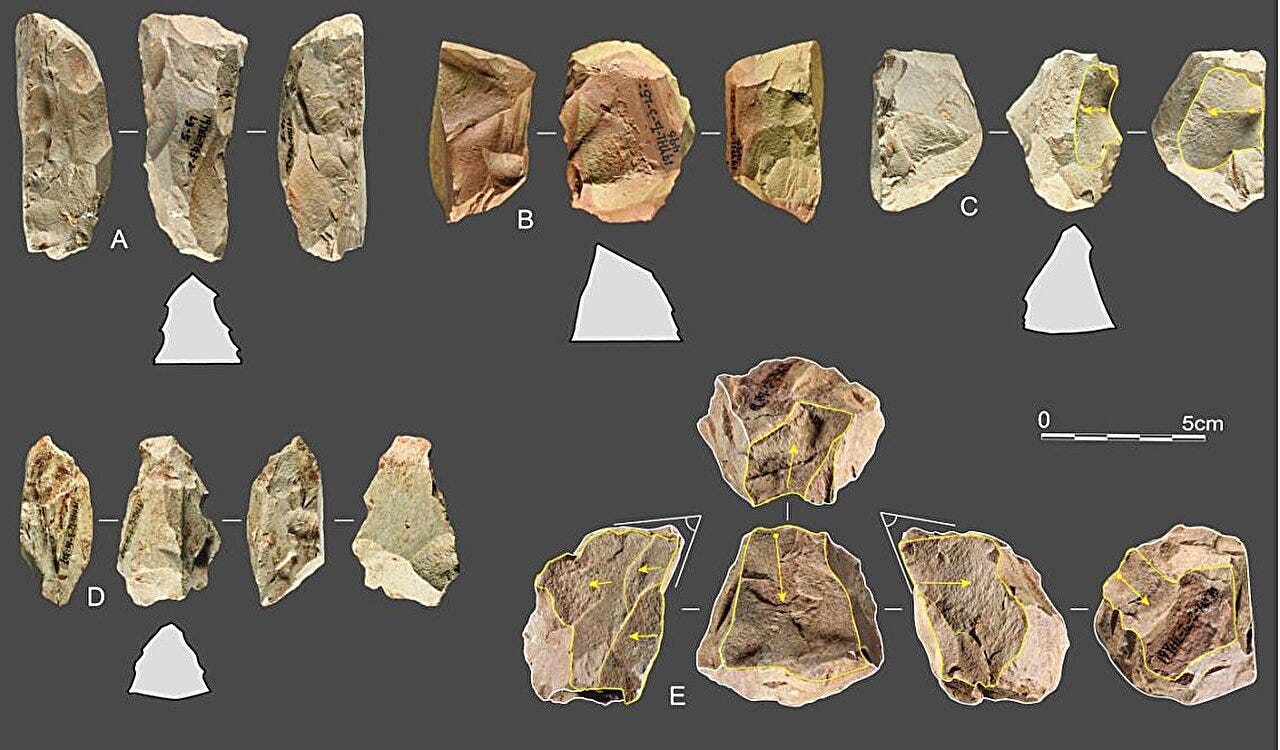

At Longtan, researchers uncovered 53 Quina scrapers and 14 cores—blocks of stone from which scrapers were struck. Microscopic wear analysis confirmed that the tools had been used for scraping animal hides, processing antlers, and possibly woodworking. These artifacts suggest that the inhabitants of Longtan were engaging in complex tool-making behavior typically attributed to Neanderthals in Europe.

Who Made the Tools?

The presence of Quina technology in China presents a major mystery: who made these tools, and how did this technique travel nearly a continent away from its known origins?

"This is a big upset to the way we think about that part of the world in that period of time," says Ben Marwick, an archaeologist at the University of Washington and co-author of the study. "It really raises the question of, what else were people doing during this period that we haven't found yet?"

The prevailing hypothesis is that Neanderthals, or at least their tool-making traditions, never reached East Asia. Instead, the region was home to Homo sapiens, Denisovans, and possibly other hominin groups. The presence of Quina tools at Longtan suggests one of two possibilities: either these populations independently developed Quina-like technology, or knowledge of this technique was somehow transmitted across vast distances.

"If Quina appears without any sign of experimentation, that suggests this was transmitted from another group," explains Marwick. "But if we see earlier stages of development, it might suggest that people in East Asia were innovating on their own."

A Closer Look at the Denisovans

One potential candidate for the creators of the Longtan Quina tools is the Denisovans, a mysterious group of archaic humans closely related to Neanderthals. While Denisovans are best known from DNA evidence and a few fossil fragments found in Siberia and Tibet, their archaeological footprint remains largely unknown. Could they have developed or adopted Quina technology?

Archaeologist Davide Delpiano, a specialist in Paleolithic tool industries, suggests that environmental pressures may have driven Denisovans or other East Asian hominins to create highly effective, reusable tools like Quina scrapers.

"Versatile, reusable Quina tools greatly assisted mobile groups that faced increasingly cold and harsh environments," says Delpiano. "Under that pressure, Denisovans or possibly still-undiscovered Asian hominid populations may have independently devised Quina tools."

If Denisovans were responsible, this would provide the first material culture directly linked to them. However, no definitive Denisovan fossils have been found at Longtan, leaving the question open.

Independent Invention or Cultural Transmission?

Another possibility is that the Quina toolkit developed independently in East Asia. The idea of convergent evolution in tool-making isn’t new—similar technological innovations have appeared in different parts of the world without direct contact. However, determining whether the Longtan tools are the result of independent innovation or cultural diffusion will require more archaeological discoveries.

Marwick and his team are searching for stratified sites with deep layers of artifacts that could reveal whether earlier forms of Quina-like tools existed in the region before the fully developed examples at Longtan.

"We can try to see if they were doing something similar beforehand that Quina seemed to evolve out of," Marwick says. "Then we might say that development seems to be more local—they were experimenting with different forms in previous generations, and they finally perfected it."

Implications for Human Evolution

The discovery of Quina technology in China is more than just an archaeological curiosity—it reshapes the understanding of how ancient human populations interacted, innovated, and adapted. If Quina tool-making spread through contact between hominin groups, it suggests a greater degree of communication and mobility between ancient populations than previously thought. If it emerged independently, it highlights the ingenuity and adaptability of prehistoric toolmakers in East Asia.

Future research will focus on finding human remains associated with Longtan’s artifacts. A direct link between these tools and Homo sapiens, Denisovans, or another hominin group could offer crucial insights into the makers of this unexpected technology.

"That could answer the question of whether these tools are the product of a modern human like you and me," says Marwick. "Or, more likely, could we find a Denisovan? Or maybe even a new human ancestor that we don't know about yet?"

Further Reading

For those interested in exploring related research:

Ruan, Q.-J., et al. (2025). "Quina lithic technology indicates diverse Late Pleistocene human dynamics in East Asia." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 122(14), e2418029122. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2418029122

de Beaune, S. A. (2022). "The Role of Children in the Upper Paleolithic: Evidence from Finger Flutings in French Caves." Journal of Archaeological Science, 137, 105542.

Cooney Williams, M., & Janik, L. (2018). "Learning Through Doing: The Role of Children in the Transmission of Cultural Knowledge via Participation in Rock Art." Childhood in the Past, 11(2), 103-119.

As new sites continue to be discovered, the story of human evolution in East Asia is proving to be far more complex than once believed.

Share this post