Archaeology often deals with what remains—the bones, the stone tools, the charred remnants of ancient hearths. But in the upland regions of Warner Valley, Oregon, a different kind of evidence is telling the story of early human diets: microscopic starch granules trapped in the cracks of bedrock metates. These stone grinding surfaces, found alongside rock art panels and other cultural features, are yielding the first direct evidence of plant processing in this landscape.

A study published in American Antiquity1 analyzed starch residues from 58 bedrock metates and identified granules from biscuitroot (Lomatium spp.), a geophyte that has been an important food source for Indigenous communities in the region for thousands of years.

A Closer Look at the Bedrock Metates

Unlike portable grinding stones, bedrock metates are stationary features—shallow depressions worn into rock surfaces through repeated use. While their presence at archaeological sites suggests food processing activities, confirming what they were used for has been difficult. The study authors, led by archaeobotanist Stefania Wilks, hypothesized that plant starches might have been preserved deep in the stone’s crevices, protected from erosion and weathering.

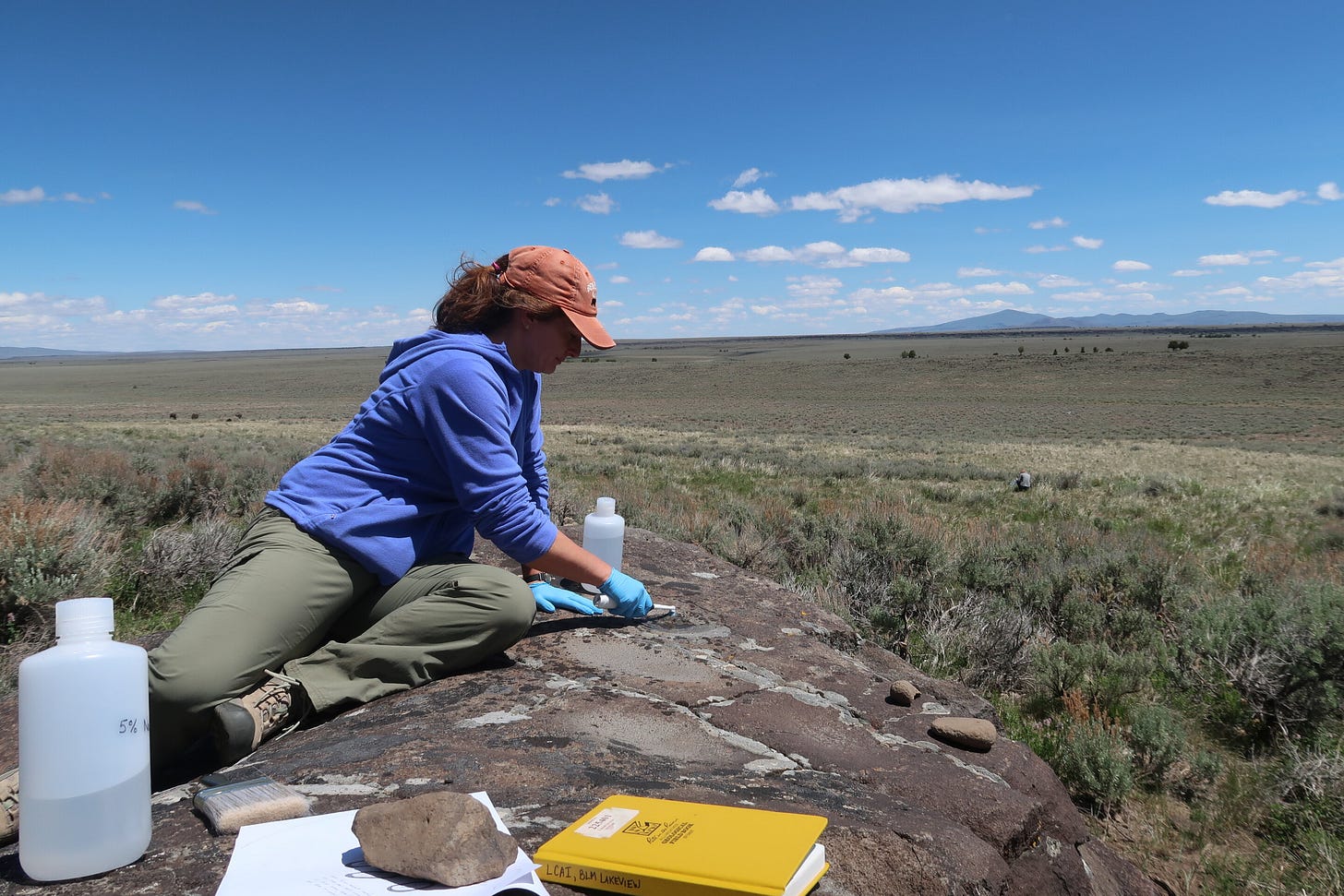

To test this, researchers sampled metates from three rock art sites in Warner Valley: Corral Lake, Barry Spring, and Long Lake. They used a two-step extraction process—first scrubbing the surface of the metates and then applying a chemical deflocculant to dislodge starch granules trapped in microscopic crevices.

"It was critical to distinguish between surface contamination and deeply embedded residues," Wilks explained. "By comparing the results, we could confirm that these starches were not recent additions but rather remnants of ancient plant processing."

Biscuitroot and the Role of Geophytes in Early Diets

The analysis identified starch granules from a range of plants, but Lomatium spp. stood out. The plant, commonly known as biscuitroot, is a member of the carrot family (Apiaceae), and its starchy taproots have long been valued for their nutritional properties.

"Geophytes like biscuitroot are an incredibly resilient food source," Wilks said. "They store carbohydrates underground, making them available even in dry or cold seasons. This would have been crucial for past hunter-gatherer groups in the northern Great Basin."

Ethnographic accounts describe Indigenous groups harvesting Lomatium with digging sticks in the spring, pounding the roots into cakes for long-term storage. The starch granules extracted from the metates closely matched those of modern Lomatium, providing direct evidence that these plants were ground and processed on-site.

Ancient Kitchens in the Landscape

The study also suggests that these rock art sites were not just places of symbolic expression but were directly linked to subsistence activities. The presence of grinding surfaces near large stands of edible plants supports the idea that people returned to these locations seasonally, taking advantage of the natural abundance.

Interestingly, the researchers found evidence that some metates had been reused over long periods. Patina analysis showed that some surfaces bore signs of older grinding activity, with newer use-wear overlaid on top.

"This pattern indicates that these places held significance over generations," Wilks noted. "People were returning to the same spots, likely because of their proximity to reliable food sources."

Revising Assumptions About Early Foraging Strategies

The discovery challenges long-standing assumptions that upland environments were primarily used for hunting rather than plant processing. Archaeologists have long associated high-elevation sites with seasonal game tracking, but the presence of grinding tools and starch granules suggests a more complex picture.

"As archaeologists, we've tended to focus on hunting as the primary activity at these sites," Wilks said. "But this evidence forces us to think more broadly about what people were doing in these landscapes. They weren’t just chasing game; they were processing plant foods in ways that left lasting traces in the stone."

The findings also add to a growing body of research demonstrating that geophytes were a staple in early North American diets. Previous studies have identified geophyte starch in sites dating back to the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene, reinforcing the idea that plant foods played a central role in subsistence strategies.

A New Tool for Studying Ancient Diets

The success of starch analysis in this study highlights the potential of the method for investigating ancient diets in other open-air settings. While charred seeds and pollen can sometimes provide clues about plant use, starch granules offer a more direct link to food processing.

"This approach is especially valuable in places where organic remains don’t typically preserve well," Wilks said. "By looking at the microscopic residues left behind, we can reconstruct aspects of daily life that would otherwise be invisible in the archaeological record."

The research team hopes to expand their work to other regions, testing whether similar grinding features elsewhere in the Great Basin contain preserved plant residues.

"What we’re seeing here may be part of a much broader pattern," Wilks said. "These upland sites may have been essential food processing locations for thousands of years, and we’re just beginning to understand their role in the larger subsistence landscape."

Related Research

For those interested in further reading on starch analysis and geophyte use in early diets, here are some key studies:

Louderback, L. A., & Pavlik, B. M. (2017). "Starch Granule Evidence for the Earliest Potato Use in North America." PNAS, 114(29), 7606–7610. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1707710114

Herzog, N. M., & Lawlor, A. T. (2016). "Reevaluating Diet and Technology in the Archaic Great Basin Using Starch Grain Assemblages from Hogup Cave, Utah." American Antiquity, 81(4), 664–681. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0002731600101027

Henry, A. G. (2020). "Starch Granules as Markers of Diet and Behavior." In Handbook for the Analysis of Micro-Particles in Archaeological Samples. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51103-2_5

This study provides a powerful reminder that even the smallest traces—microscopic starch granules—can reshape our understanding of human history.

Wilks, S. L., Louderback, L. A., Simper, H. M., & Cannon, W. J. (2025). Starch granule evidence for biscuitroot (Lomatium spp.) processing at upland rock art sites in Warner Valley, Oregon. American Antiquity, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2024.42

Share this post