Farming After the Fire

The Neolithic Revolution has long been framed as a triumph of human ingenuity—the dawn of agriculture, of domestic animals, of sedentary villages. But what if this turning point wasn’t planned at all? What if it began as an act of survival?

A recent study by Prof. Amos Frumkin of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem offers a different lens. Published in the Journal of Soils and Sediments1, the research proposes that widespread wildfires and hillslope erosion—not cultural innovation alone—may have created the ecological conditions that forced people to abandon foraging and begin farming across the southern Levant.

The shift, Frumkin argues, wasn’t just a matter of discovery. It was a response to catastrophe.

“These fires likely removed vast tracts of vegetation,” Frumkin writes.

“This led to severe soil degradation on hillslopes and the accumulation of fertile soil in valley basins—ideal locations for early farming communities.”

A Landscape on the Edge

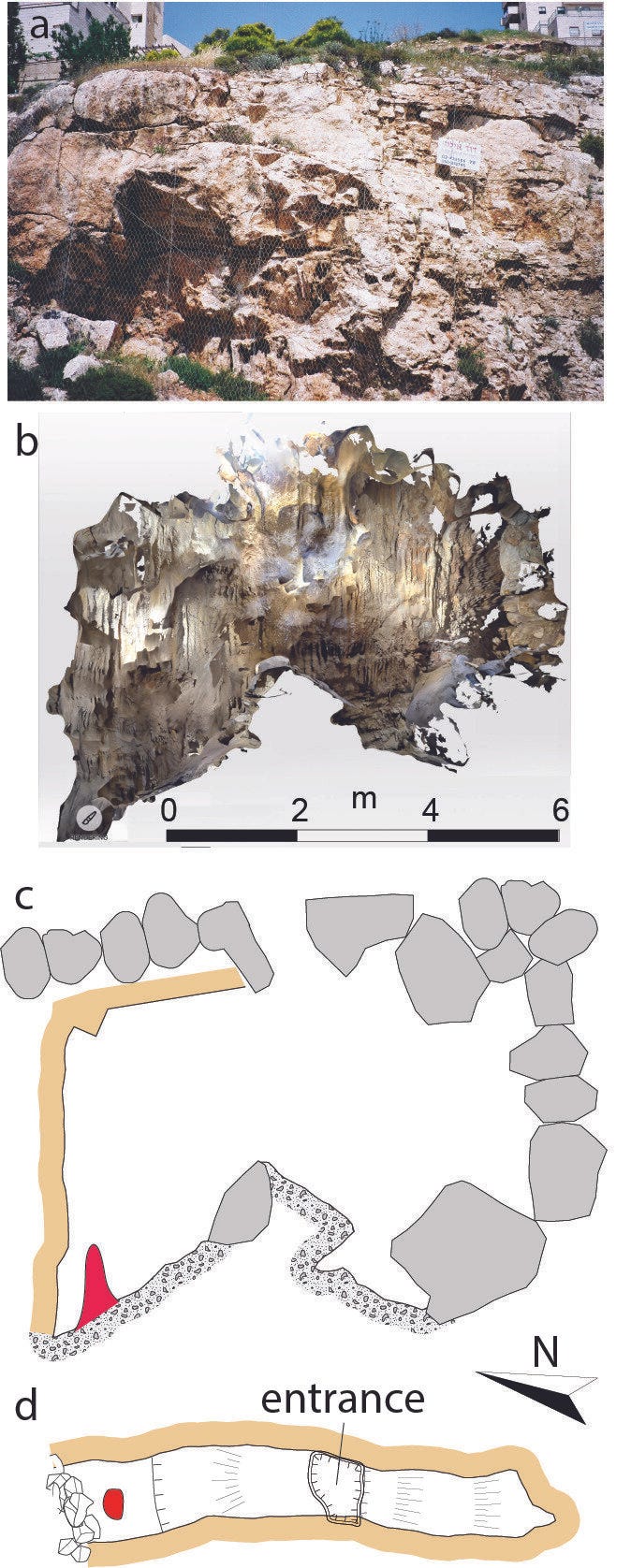

Frumkin’s team stitched together data from an unusual cross-section of the Earth: lakebeds, speleothems in caves, Dead Sea levels, and sediment cores from ancient soils. Each layer told part of the story. The most telling signal? Micro-charcoal embedded in lake sediments and cave formations dating to around 8,200 years ago.

This period aligns with the 8.2 kiloyear event—a dramatic climate dip tied to changes in solar radiation and monsoon circulation. In the Levant, it triggered intense, dry thunderstorms. Lightning strikes set the parched hills ablaze, torching forests and grasslands across what’s now Israel, Jordan, and Lebanon.

“Our findings point to an intense period of natural wildfires and vegetation collapse caused by increased lightning during the early Holocene,” said Frumkin.

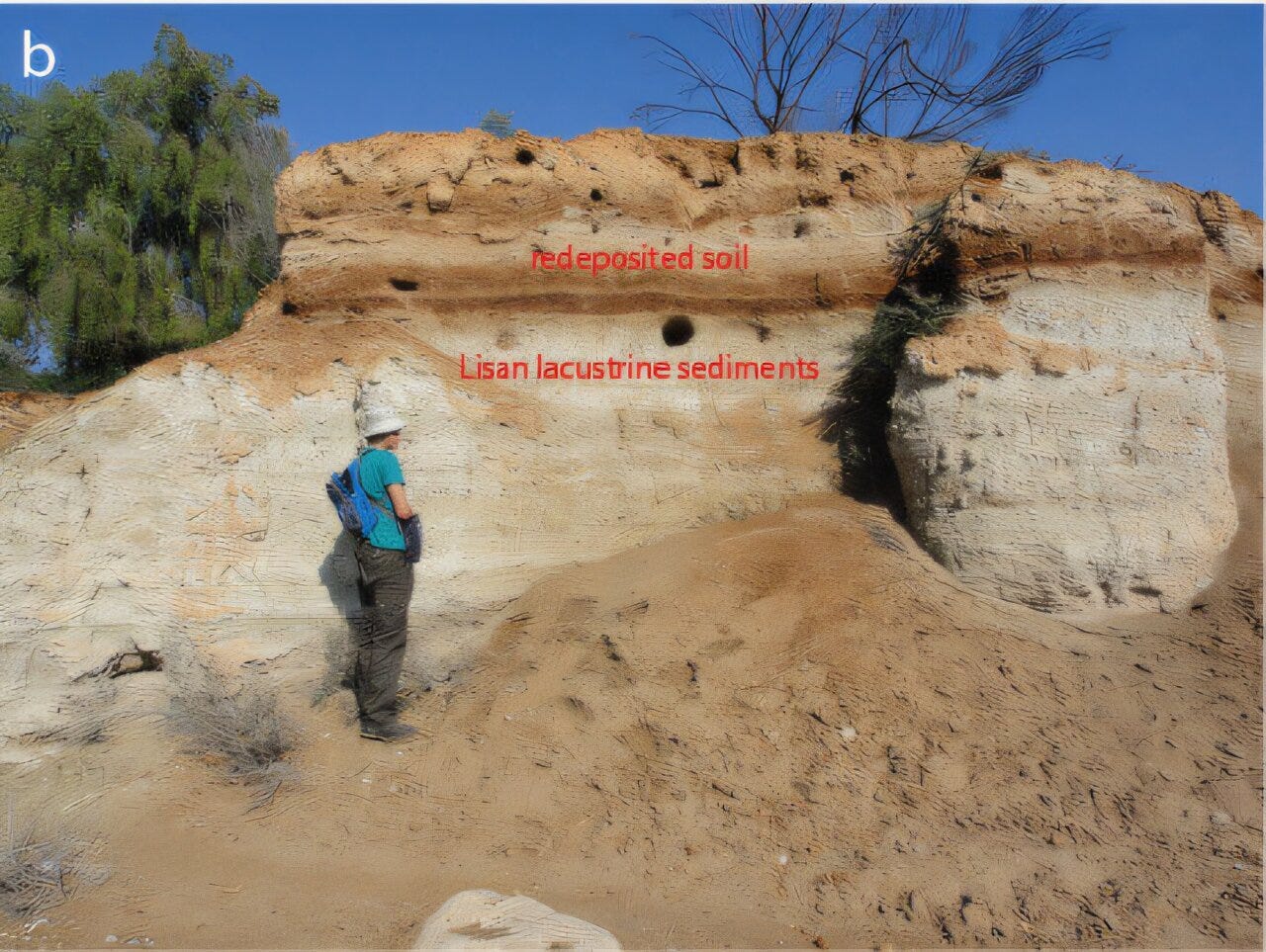

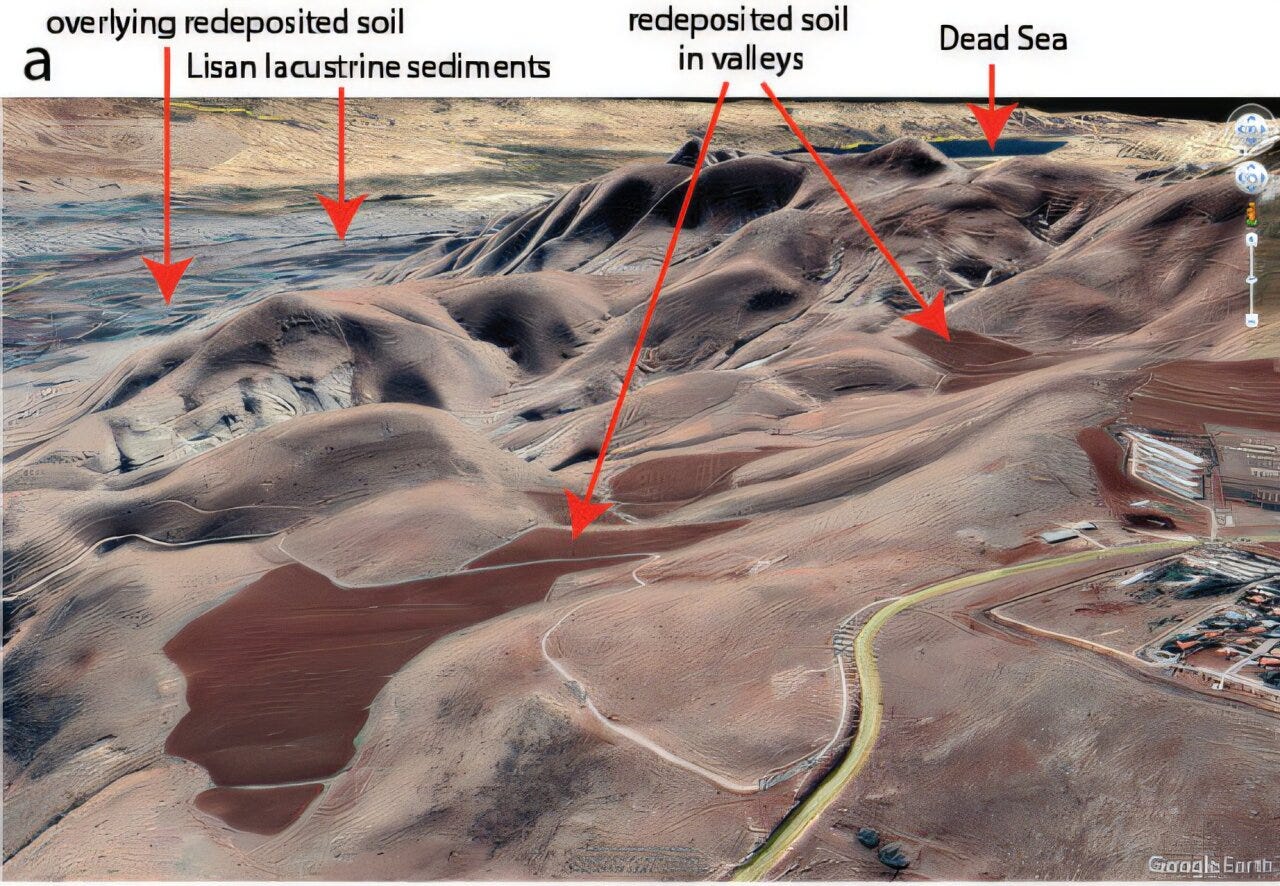

The fires were not isolated. They coincided with other disruptions: falling Dead Sea levels, shifts in carbon and strontium isotopes, and evidence of soil movement from uplands to lowlands.

From Hills to Valleys: Where Fertility Gathered

After the fires, the hills became unstable. Without roots to hold the earth, soil washed downslope during rains, accumulating in the valleys—low-lying, water-rich areas that became, quite literally, the cradle of agriculture.

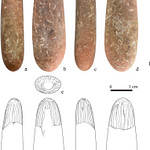

The soil deposits in these basins were rich, reworked, and thick—prime ground for Neolithic settlements. Archaeological surveys show that many of the region’s earliest farming villages clustered along these alluvial fans and floodplains, especially in the Jordan Valley.

“Neolithic settlements in the southern Levant clustered over thick reworked soil deposits,” the study notes. “These soils, derived from eroded hillsides, offered both fertility and access to water—key ingredients for early agriculture.”

This geography of settlement suggests that farming didn’t begin where it was easiest to live—but where it was possible to survive.

Collapse, Not Choice

The popular narrative of the Neolithic often centers on progress. Humans, it is said, chose to sow, plant, domesticate. But Frumkin’s work adds a different voice to the chorus: adaptation, not ambition.

“This wasn’t a gradual cultural shift,” Frumkin argues. “It was a response to environmental collapse.”

In this version of prehistory, farming wasn’t a brilliant idea. It was what came after the forests fell and the hills began to bleed.

Archaeological layers show clear traces of this transformation. Flint tools give way to sickles. Storage pits emerge. Animal bones shift in species and age profile, reflecting herding. What’s missing is the gradual buildup that would mark a purely human-engineered transition.

Lessons in Fire and Soil

Today, the idea that climate change reshapes civilizations is no longer academic. But Frumkin’s study is a reminder that environmental crises have shaped humanity before—and may do so again.

His reconstruction of early Holocene southern Levant is not a romantic one. It’s a picture of charred ground, thinning forests, and collapsing ecosystems. Yet it’s also a story of resilience—of how humans, faced with fire and flood, turned ash into grain.

“Agriculture and settlement patterns were likely shaped by necessity, not just innovation,” the paper concludes.

This reframing does not diminish the Neolithic—it complicates it. Farming was not simply the birth of civilization. It was a way through crisis. And perhaps, a fragile one.

Further Reading and Related Research

Rosen, A. M. (2007). Civilizing Climate: Social Responses to Climate Change in the Ancient Near East. Rowman Altamira.

Weiss, H., & Bradley, R. S. (2001). What drives societal collapse? Science, 291(5504), 609–610. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.291.5504.609

Bar-Yosef, O. (2011). Climatic fluctuations and early farming in West Asia. Current Anthropology, 52(S4), S175–S193. https://doi.org/10.1086/658368

Maher, L. A., et al. (2011). Hunter-gatherers and early sedentism in the Jordan Valley. Journal of Field Archaeology, 36(1), 29–42. https://doi.org/10.1179/009346911798356793

Frumkin, A. (2025). Catastrophic fires and soil degradation: possible association with the Neolithic revolution in the southern Levant. Journal of Soils and Sediments. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-025-04021-x

Share this post