The Forgotten Burden

In the sun-drenched valleys of Bronze Age Nubia—modern-day Sudan—women moved through the rural landscape with baskets balanced on their heads and tumplines wrapped tightly around their foreheads. These were not symbolic acts of endurance. They were survival.

More than 3,500 years later, the imprint of that daily labor is still inscribed in bone.

At Abu Fatima, an ancient cemetery near the capital city of Kerma, a new study has taken a closer look at the skeletal remains of 30 individuals, unearthing physical traces of a world where the labor of women was essential, taxing—and all but erased from traditional historical narratives. The research, led by Jared Carballo and Uroš Matić, now published in the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology1, is a reminder that human history is often told through what survives—but also what is overlooked.

“In some way, the study reveals how women literally have carried the weight of society on their heads for millennia,” notes Carballo.

Bones as Biographies

Archaeology often begins with fragments—pottery, tools, a cracked tooth—but what happens when the evidence of daily life is the body itself?

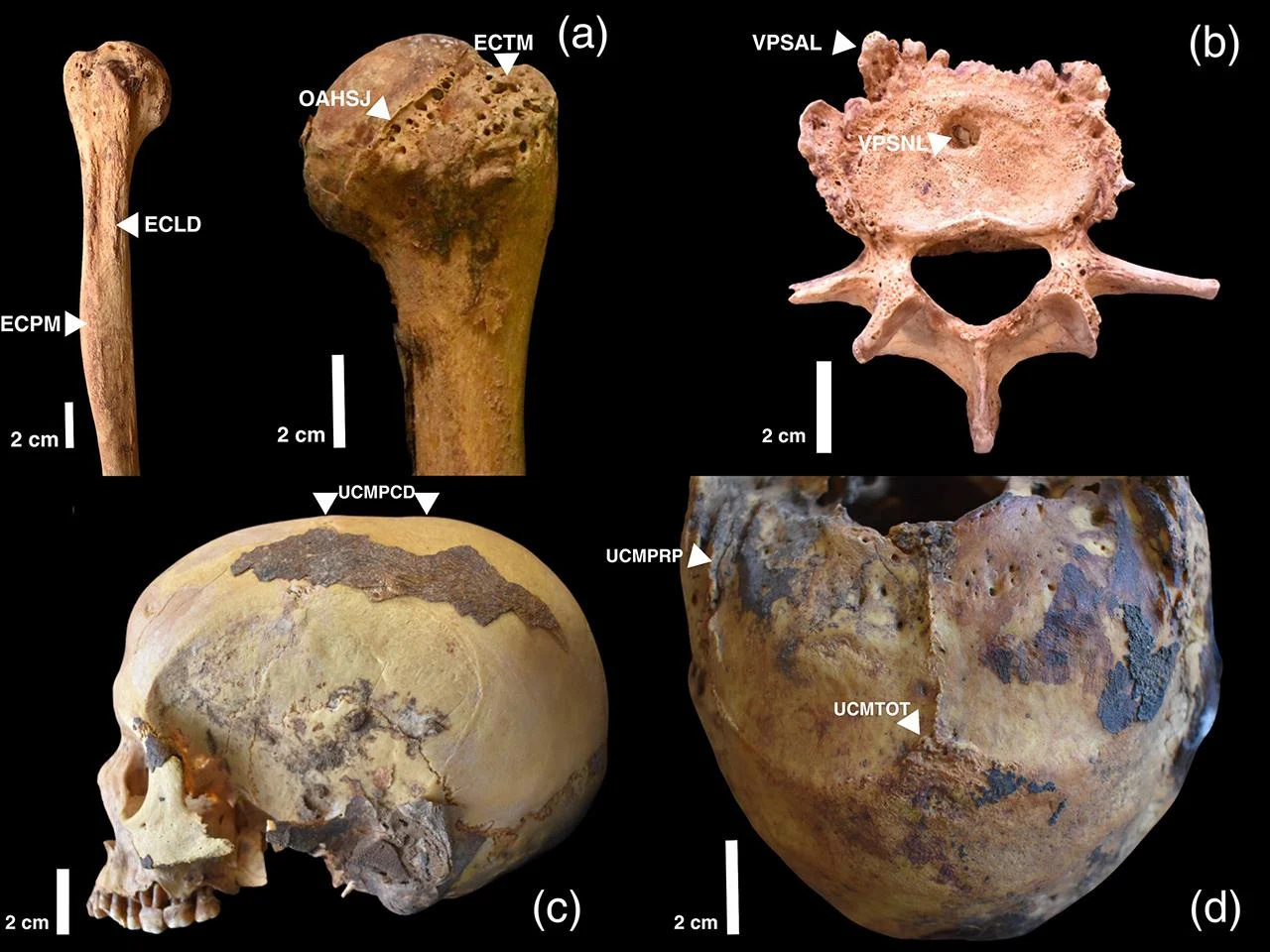

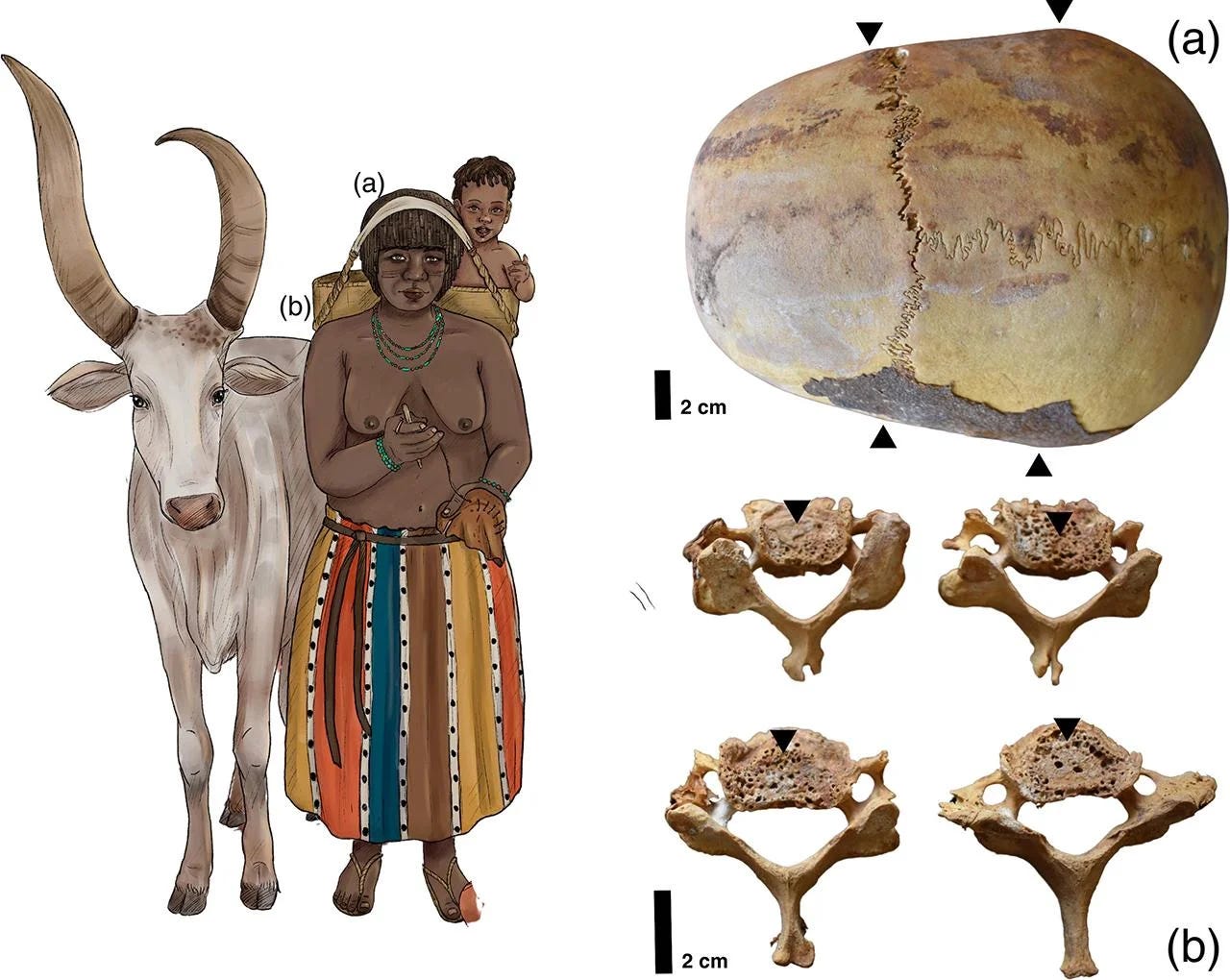

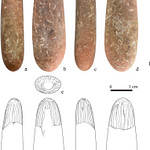

Carballo and Matić's team employed a deeply interdisciplinary approach: osteological analysis, ethnography, and iconographic comparison across North Africa and the eastern Mediterranean. The site at Abu Fatima provided a compelling case. Of the 14 women studied, many showed specific changes to the cervical vertebrae and upper skull—patterns consistent with long-term head-loading using tumplines, straps that pass from the forehead over the top of the head and connect to a load.

In contrast, male skeletons from the same cemetery showed signs of different stress: asymmetrical strain on the shoulders and arms, especially the right side—likely from shoulder- or arm-carrying methods.

One woman in particular, labeled individual 8A2, emerged as especially telling. She had lived past 50—an advanced age for the Bronze Age—and was buried with prestige items: a leather cushion and an ostrich feather fan. But her body told another story.

Her skull bore a deep depression behind the coronal suture, and her neck vertebrae showed evidence of severe osteoarthritis—consistent with decades of carrying weight by tumpline.

Chemical analysis of her dental enamel suggested she wasn’t born locally. She was a migrant who had likely adapted to the demands of rural life in Nubia—perhaps transporting water, food, or children across long distances in the heat.

Hers was a life of movement, strain, and invisible labor.

The Gendered Architecture of Bone

These findings support a growing current in anthropological research: that bones aren’t just biological—they’re cultural. They record how bodies move, how labor is divided, and how roles are rehearsed, imposed, and endured over time.

This perspective draws on concepts like body techniques (the culturally specific ways bodies are used in everyday life) and gender performativity (the idea that gender is enacted through repeated behaviors, not simply inherited). Together, they help explain how physical difference isn’t always about biology, but about experience.

“Bone modifications are not simply the result of aging,” the authors write.

“They also reflect social patterns, such as the division of labor and gender roles.”

This daily burden was not merely physical. It was generational. Ethnographic records show that head-carrying—still common across rural Africa, Asia, and Latin America—is a learned technique, taught early and refined over time. Carballo’s team traced this practice not just through bones, but through ancient Egyptian tomb paintings, where Nubian women appear with baskets high atop their heads, performing labor that would never be mentioned in royal decrees or temple inscriptions.

Carriers of Memory

The archaeological record is full of silences. War leaves monuments. Trade leaves amphorae. But women’s labor—especially domestic or logistical—rarely leaves written traces.

Head-loading may seem mundane, but its physical toll reveals the foundational roles women played in ancient economies. Transporting food and water, moving goods between households or villages, even bearing children—this was the infrastructure of survival. And like so much women’s labor, it was essential yet historically invisible.

“Head-loading was not only a physical effort but also a material expression of inequality and resilience,” the study concludes.

In individual 8A2, we find more than arthritis. We find a story. A woman from elsewhere who spent her life in motion, whose every step left pressure on the spine and grooves in the bone. And when her body was finally still, she was buried with both status and wear—an emblem of how prestige and labor were not mutually exclusive.

Toward a More Complete Past

The Abu Fatima findings open new windows onto the social fabric of ancient Nubia. They suggest lines of future inquiry—about migration, logistics, women’s mobility, and the physical demands of motherhood and daily sustenance in ancient agrarian societies.

But they also raise important questions about what histories get told—and who gets left behind.

The story of human evolution has too often prioritized hunting over hauling, spear-throwing over child-carrying, war over water-fetching. But to understand ancient societies in full, researchers must look at the labor that built them—from the ground up.

Sometimes, that labor leaves behind amphorae or grain silos. Other times, it leaves behind a vertebra compressed by decades of silent work.

Related Research & Further Reading

Schrader, S. A., & Smith, S. T. (2019). Gendered labor and bioarchaeology: Reconstructing women's work in the ancient Nile Valley. Current Anthropology, 60(3), 350–375. https://doi.org/10.1086/703171

Ogundiran, A. (2020). The Yoruba: A New History. Indiana University Press. (Chapters on embodied labor and gender roles in West African archaeology)

Robb, J., & Harris, O. (2013). The body in history: Europe from the Paleolithic to the future. Cambridge University Press.

Kusimba, C. M. (2021). Matriarchs, merchants, and slaves: Archaeologies of social complexity in coastal Kenya. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 63, 101305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2021.101305

Carballo-Pérez, J., Matić, U., Hall, R., Smith, S. T., & Schrader, S. A. (2025). Tumplines, baskets, and heavy burden? Interdisciplinary approach to load carrying in Bronze Age Abu Fatima, Sudan. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 77(101652), 101652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2024.101652

Share this post