Brains of Neanderthal & Human Share A Startlingly "Youthful" Characteristic

Particularly, strong cerebral cortical integration into maturity is a shared trait between humans and Neanderthals.

Many people think that the fact that we have such enormous brains is what makes us human, but is there more to it? The shape of the brain and the lobes that make up its constituent portions may also be significant.

The findings of a study1 that was published in Nature Ecology & Evolution demonstrate how the human brain's many components evolved differently from our primate ancestors and in summary, our brains essentially never mature. The Neanderthals are the only other primate with which we share this "Peter Pan syndrome." The discoveries further blur the line between us and our extinct ancestors while also shedding light on what makes us human.

The scientists looked for evidence that the evolution of the brain's lobes are "integrated," meaning that changes in one lobe appear to be inevitably linked to changes in others, or that the lobes evolved independently of one another. They were especially interested in how human brains might differ from those of other primates in this regard.

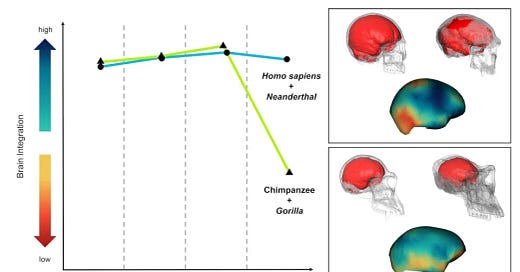

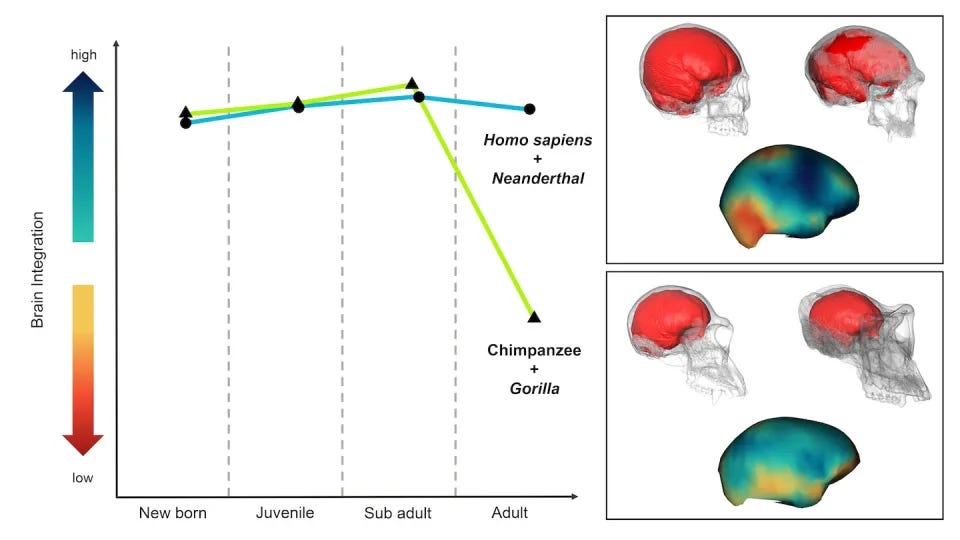

Examining how the various lobes have evolved through time in various species and determining how much each lobe's form has altered in relation to others can help answer this question. As an alternative, one can gauge how much the brain's lobes integrate with one another as an animal progresses through its many life phases.

Does a change in the form of one area of the developing brain correspond to a change in another area? Because evolutionary steps can frequently be tracked through an animal's development, this can be instructive. The brief presence of gill openings in early human embryos is a typical illustration, highlighting the fact that we may trace our evolutionary history back to fish.

The writers employed both techniques.

As well as humans and our near fossil ancestors, the first analysis included 3D brain models of hundreds of live and extinct primates, including monkeys, apes, and living primates. This enabled them to chart the evolution of the brain throughout time.

They were able to illustrate how the various components of the brain integrate as different species mature using the other digital brain data set, which included living ape species and humans at various maturation phases. The brain models were created using CT scans of human skulls, and by digitally filling in the brain cavities, the form of the brain was roughly approximated.

The findings were surprising. They discovered that humans had exceptionally high degrees of brain integration, notably between the parietal and frontal lobes, by tracking change over long stretches of time across dozens of monkey species. But they also discovered that we're not alone. In Neanderthals as well, there was a significant degree of integration between these lobes.

Up until puberty, the integration of the brain's lobes in apes, like the chimpanzee, is similar to that of humans, according to research on shape changes that occur during development. The apes' integration rapidly declines at this point, whereas in humans, it persists long into adulthood.

What does all of this mean, then?

The findings imply that human beings are unique from other primates in more ways than merely having larger brains. Unlike any other living monkey, our brain's many components have evolved more thoroughly together, and this integration has persisted into adulthood.

Juvenile life stages are often connected with a stronger potential for learning. They contend that the development of human intelligence was significantly influenced by this Peter Pan syndrome.

Another significant implication follows… See, it has becoming more and more obvious that Neanderthals, long stereotyped as brutish cavemen, were in fact clever, sophisticated beings. Archaeological discoveries, including the oldest known traces of string, manufactured musical instruments and jewelry, as well as the production of tar, continue to bolster the theory that they developed complex technologies. Neanderthal cave art demonstrates that they engaged in sophisticated symbolic cognition and buried their dead in ceremonial ways.

The outcomes further obfuscate any boundary between us and them. Many people still believe that humans had some sort of intellectual advantage that allowed us to eradicate our less intelligent cousins. One group of people may rule over or even exterminate another for a variety of reasons.

Prior researchers looked for cranial characteristics associated with higher IQ to explain the dominance of Europe. Of course, we now know that the shape of the skull has nothing to do with it.

In actuality, 70,000 years ago, we humans were very close to going extinct. If humans hadn't perished, perhaps Neanderthal descendants today would be puzzling over how their higher intelligence gave them the upper hand.

Sansalone, G., Profico, A., Wroe, S. et al. Homo sapiens and Neanderthals share high cerebral cortex integration into adulthood. Nat Ecol Evol 7, 42–50 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-022-01933-6