Life After the Ice

The windswept floor of Mongolia’s Gobi Desert doesn’t readily reveal its secrets. But beneath its cracked sediment and the shifting shoreline of long-vanished lakes, archaeologists are beginning to piece together a story not just of survival—but of deep cultural adaptation.

In a new study published in Radiocarbon1, a team led by Dr. Przemysław Bobrowski presents firm evidence that hunter-gatherer communities were living—and experimenting with pottery—along the paleolakes of the Gobi nearly 11,200 years ago. That’s nearly 2,000 years earlier than previously assumed for the region.

“The dates we have obtained show that the knowledge of making pottery vessels reached the Gobi Altai region almost 2,000 years earlier than previously thought,” Bobrowski explains. “Chronologically, they correspond, for example, to early dates for pottery from northern China.”

The study focuses on sites near Lake Baruun Khuree in the Tsakhiurtyn Hundi (Flint Valley) region, roughly 700 kilometers south of Ulaanbaatar. This high desert basin, ringed by the Arts Bogdyn Nuruu massif, has long been known for its flint outcrops and Paleolithic tool workshops. But the new findings suggest that its human story stretches well into the early Holocene—with pottery, ostrich eggshell jewelry, and evidence of lakeshore settlement.

A Quiet Revolution in Clay

In the archaeological record of East and Central Asia, the earliest ceramics are often associated with the late Upper Paleolithic to Mesolithic transition—typically tied to slow-burning hearths, storage pits, and seasonal camps. Yet the Baruun Khuree sites offer something more definitive: a tight correlation between pottery fragments and securely dated hearths, using eleven radiocarbon samples calibrated between 11,251 and 10,535 years before present.

This matters.

For decades, Mongolia’s earliest pottery had been pegged to around 9,600 cal BP. The new dates from Baruun Khuree push the timeline back by nearly two millennia, placing the Gobi alongside some of the earliest ceramic-producing cultures of northeast Asia.

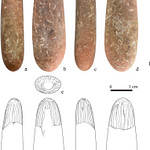

The ceramics themselves are distinctive—gray to reddish in color, with a thickness rarely exceeding 7 to 8 millimeters. Their simplicity belies their significance: they represent not just an innovation, but the transmission of an idea across landscapes that, by modern standards, seem forbiddingly vast.

Ostrich Beads and the Material Memory of the Steppe

The Gobi Desert was never a cultural void. Among the most evocative finds from the Baruun Khuree sites are fragments of ostrich eggshells—some fashioned into pendants, others into beads.

These aren’t random curiosities. They speak to long-standing symbolic practices in early Holocene Central Asia, where Struthio anderssoni, the now-extinct East Asian ostrich, once roamed. The production of eggshell ornaments—requiring precise drilling, grinding, and polishing—suggests skilled craftsmanship and cultural continuity with Pleistocene traditions found further south and east.

“Ostrich eggshell beads and pendants were discovered at the excavated sites,” the team reports. “These artifacts, along with the lithics and ceramics, help define a distinctive material culture near the Gobi’s paleolakes.”

Lakes that Remember

The paleolakes themselves—now little more than saline flats and ghosted shorelines—were once freshwater basins fed by glacial melt and Holocene precipitation. During the post-Last Glacial Maximum warming, these lakes became magnets for human activity.

Archaeological survey around the paleolake network south of the massif revealed not just occupation, but deliberate site selection. Camps like FV 133, FV 134A, and FV 139 offered access to freshwater, toolstone, game, and—crucially—social space.

“Surface prospection revealed the existence of a network of paleolakes... and numerous sites associated with communities inhabiting this area in the Pleistocene,” says Bobrowski.

One site, FV 139, yielded the oldest dates: between 11,251 and 11,196 cal BP. Younger occupations—still well within the early Holocene—were found at the other Baruun Khuree sites. Together, these chronologies point to seasonal or cyclical return, perhaps over multiple generations.

Pottery Without Agriculture

What makes this find especially compelling is what’s missing: domesticated plants or animals. Unlike Neolithic cultures in the Near East or China, these early Holocene groups in Mongolia were foragers—not farmers.

Yet they made pottery.

This defies the classic narrative that ties ceramics to agricultural surplus. Instead, it echoes findings from Japan’s Jōmon culture or Siberian taiga groups, where ceramic innovation arose among complex hunter-gatherers managing aquatic or lacustrine ecosystems.

“Baruun Khuree appears to represent one of the earliest securely dated episodes of Holocene hunter-gatherer activities in the Gobi desert,” the authors argue.

In this view, pottery may have emerged not from sedentism, but from mobility: light, transportable containers for boiling, brewing, or storing precious resources near lake margins.

Toward a Deeper Timeline of Gobi Prehistory

Mongolia’s archaeological record is sparse when it comes to early ceramics. The Baruun Khuree sites may prove pivotal—not just for recalibrating the timeline of pottery in the region, but for reframing how early Holocene communities adapted to changing environments after the Ice Age.

The team is continuing work on both the ceramic and eggshell assemblages, with further publications expected. As Bobrowski notes, this is just the beginning of what these sites can tell us:

“We are currently carrying out several specialist analyses... and another publication focusing on the pottery and ostrich eggshell adornments we discovered is in preparation.”

The Gobi, long viewed as a marginal frontier, is emerging as a center of innovation—one where people retooled their material worlds to meet the demands of a warming planet, drying lakes, and shifting migratory patterns.

Clay and shell, it turns out, still speak.

Related Research and Further Reading

Kuzmin, Y. V. (2006). Chronology of the earliest pottery in East Asia: Progress and pitfalls. Antiquity, 80(308), 362–371. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X00093676

Jordan, P., & Zvelebil, M. (2009). Ceramics before farming: The dispersal of pottery among prehistoric Eurasian hunter-gatherers. Left Coast Press.

Zhang, C., & Hung, H.-C. (2010). The emergence of agriculture in southern China. Antiquity, 84(323), 11–25. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X00099737

Kuzmin, Y. V., & Shewkomud, I. Y. (2023). Early ceramics in the Russian Far East and Mongolia: A comparative review. Archaeological Research in Asia, 35, 100416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ara.2023.100416

Bobrowski, P., Jórdeczka, M., Masojć, M., Gunchinsuren, B., Goslar, T., Sikora, R., Muntowski, P., Odsuren, D., Szmit, M., Bazargur, D., Michalec, G., & Szykulski, J. (2025). The earliest Holocene wanderers through the Gobi Desert evidenced by the radiocarbon chronology of the lakeshore settlement near the Tsakhiurtyn Hondi, Mongolia. Radiocarbon, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/RDC.2025.4

Share this post