The early human settlement of South America stands as one of the last great migrations in human history, yet the environmental conditions that shaped this journey remain debated. New research by Lorena Becerra-Valdivia, published in Nature Communications1, suggests that humans did not simply follow stable climates but adapted to fluctuating conditions, sometimes settling in areas experiencing severe cold. Using Bayesian chronological modeling and data from over 150 archaeological sites, the study examines how two major climatic events—the Antarctic Cold Reversal (ACR) and the Younger Dryas (YD)—influenced early human dispersal across the continent.

The Antarctic Cold Reversal and the First Settlements

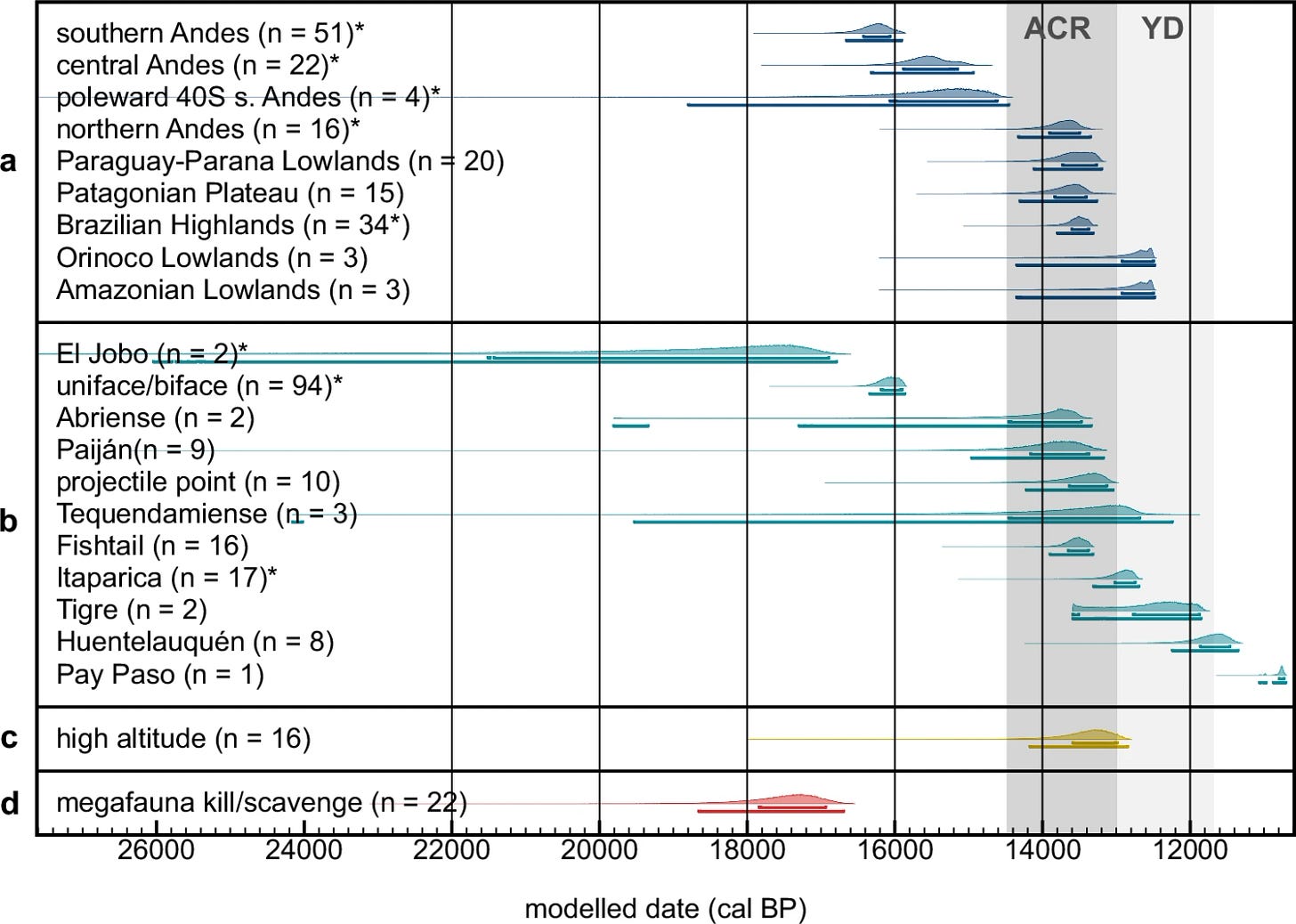

When early humans arrived in South America, they encountered a continent undergoing dramatic climate shifts. Around 14,700 to 13,000 years ago, the Southern Hemisphere experienced the Antarctic Cold Reversal, a period of cooling that reversed the warming trend seen in the Northern Hemisphere. Instead of deterring settlement, this cold phase appears to coincide with some of the earliest human activity in the region.

According to Becerra-Valdivia's study, sites in the southern Andes and Patagonia show evidence of human occupation before or during this cold phase. This suggests that early settlers may have developed cultural adaptations that allowed them to survive in colder conditions.

"The cultural timeline does not indicate that cold conditions were a barrier to human expansion," the study notes. "Rather, the earliest known human activity aligns with regions most affected by cooling, particularly in high-altitude and southernmost areas."

The findings challenge earlier assumptions that humans would have avoided these harsh environments. Instead, their ability to endure may have been aided by cumulative knowledge, allowing them to exploit diverse ecological niches despite temperature fluctuations.

The Younger Dryas and Expansion Across the Continent

Following the Antarctic Cold Reversal, the Younger Dryas—a sharp cooling event that lasted from approximately 12,900 to 11,700 years ago—brought further environmental instability. This event, however, appears to have played a different role in human settlement. The study suggests that widespread occupation of South America became more pronounced after the Younger Dryas, as conditions stabilized.

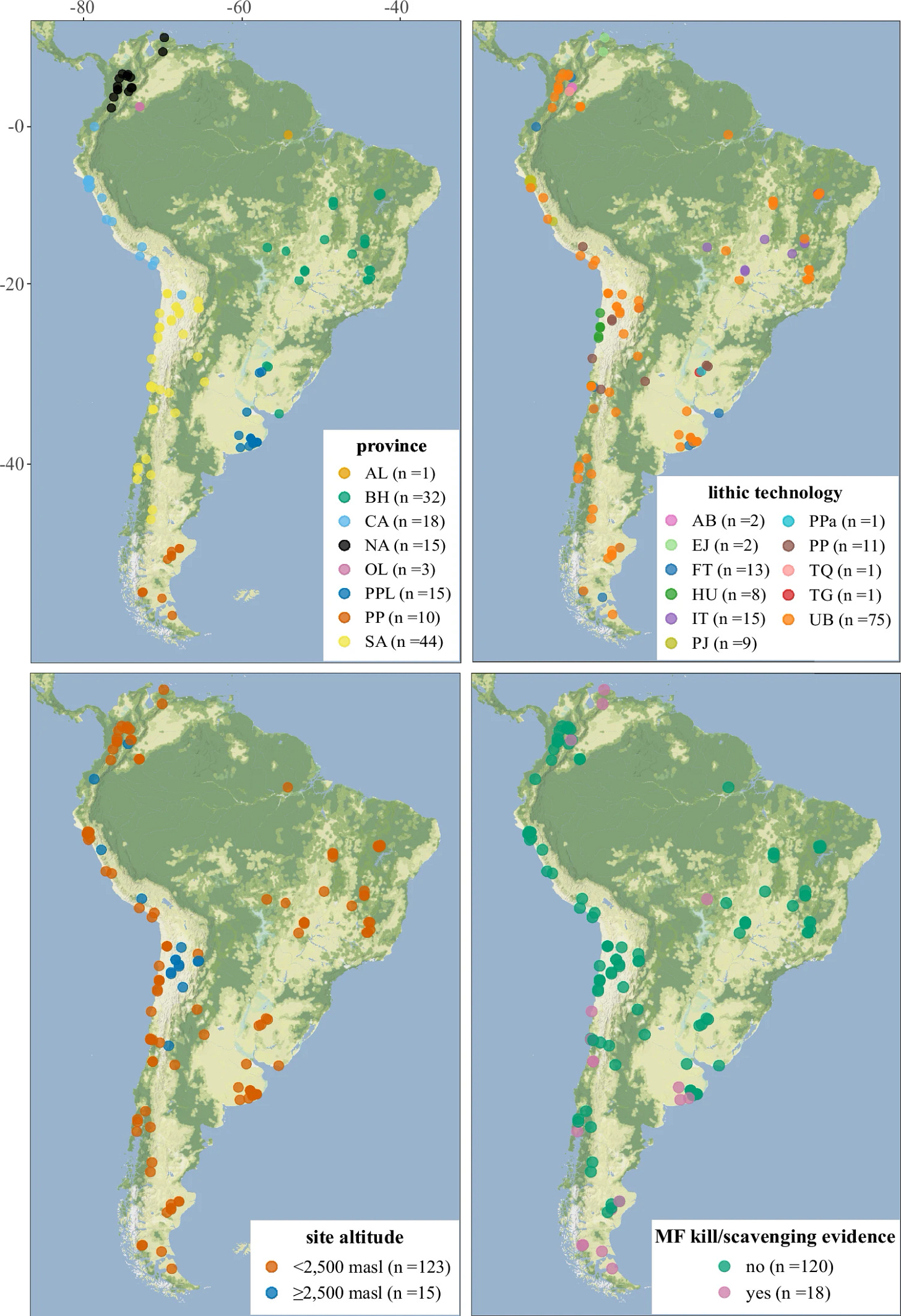

A key pattern observed in the data is a west-to-east dispersal trend. Early occupation appears concentrated in the western Andes, with later settlements spreading toward the lowlands and eastern regions.

"The Andes and the Pacific Coast likely served as primary routes for early human dispersal," Becerra-Valdivia explains. "Evidence suggests a later expansion toward interior regions such as the Paraguay-Paraná Lowlands."

This supports genetic studies indicating that the Andes played a crucial role in early South American population movements. While lowland rainforests and humid environments likely presented challenges for early settlers, the western highlands may have offered a more viable pathway for migration.

Rethinking Climate and Human Adaptation

The study also touches on a long-standing debate: were humans responsible for the extinction of South America's megafauna, or did climate play the dominant role? The archaeological evidence does not establish a clear causal link between human activity and megafaunal decline. Instead, the data suggest that hunting and scavenging of large animals, such as giant sloths and mastodons, began well before their extinction.

"The timing of megafaunal exploitation by humans does not directly align with their extinction patterns," the study states. "While human hunting may have contributed to population declines, the role of climate shifts cannot be overlooked."

This contrasts with theories that place humans as the primary drivers of megafaunal extinctions. Instead, the study emphasizes the need for more refined models that integrate archaeological, genetic, and environmental data.

Gaps in the Archaeological Record

Despite these insights, the research also highlights major gaps in the archaeological and chronometric record. Some regions, such as the Amazon and Orinoco Lowlands, are significantly underrepresented in radiocarbon dating efforts. The study calls for more systematic dating of stratified sites and improved documentation of cultural sequences.

"A more comprehensive dataset is needed to refine the cultural timeline," the study suggests. "Current gaps limit our ability to fully understand the pace and nature of early human settlement in South America."

Addressing these issues could provide a clearer picture of how humans adapted to diverse environments, from glaciated mountain ranges to humid tropical forests.

Conclusion

Rather than being driven solely by climate, early human settlement in South America appears to have been shaped by a combination of environmental shifts and cultural adaptation. The ability to inhabit regions experiencing severe cold suggests a level of resilience that may have been underestimated. As more data emerge, the story of the first South Americans continues to evolve, offering new perspectives on how humans navigated one of the most complex migrations in history.

Related Research and Citations

If you're interested in further exploring the intersection of climate and early human migration, the following studies may be of interest:

Prates, L., & Pérez, S. I. (2021). "Late Pleistocene South American megafaunal extinctions associated with rise of Fishtail points and human population." Nature Communications, 12, 2175. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22454-2

Waters, M. R., & Stafford, T. W. (2007). "Redefining the age of Clovis: implications for the peopling of the Americas." Science, 315(5815), 1122-1126. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1137166

Moreno-Mayar, J. V., et al. (2018). "Early human dispersals within the Americas." Science, 362(6419), eaav2621. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aav2621

These studies provide additional insights into the timing of human migration into the Americas and the ecological challenges early settlers faced.

Becerra-Valdivia, L. (2025). Climate influence on the early human occupation of South America during the late Pleistocene. Nature Communications, 16(1), 2780. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58134-5

Share this post