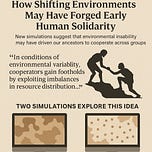

In the vast timeline of human evolution, one question has nagged at researchers more than most: how did cooperation, a risky and often costly behavior, come to define Homo sapiens?

A recent study out of the University of Tsukuba offers an unexpected answer. It wasn't stability, safety, or predictability that shaped our social instincts—it was the opposite. Through computational models based on evolutionary game theory, Masaki Inaba and Eizo Akiyama argue that environmental chaos may have pushed humans toward cooperation, particularly among scattered and resource-strapped groups.

Published in PLOS Complex Systems1, the study reframes the widely discussed “variability selection hypothesis” (VSH). Originally proposed to explain the emergence of enhanced cognitive abilities during the Middle Stone Age (MSA), the VSH posits that fluctuating African environments—oscillating between arid and humid phases—forced early humans to develop better brains. But Inaba and Akiyama suggest the pressures may have run deeper. They may have fostered not just better thinkers, but better collaborators.

“While the variability selection hypothesis has traditionally focused on individual cognitive adaptations,” the authors write, “our model demonstrates that environmental instability may also have been crucial in shaping collective behavior.”

When the Weather Doesn’t Hold, the Group Must

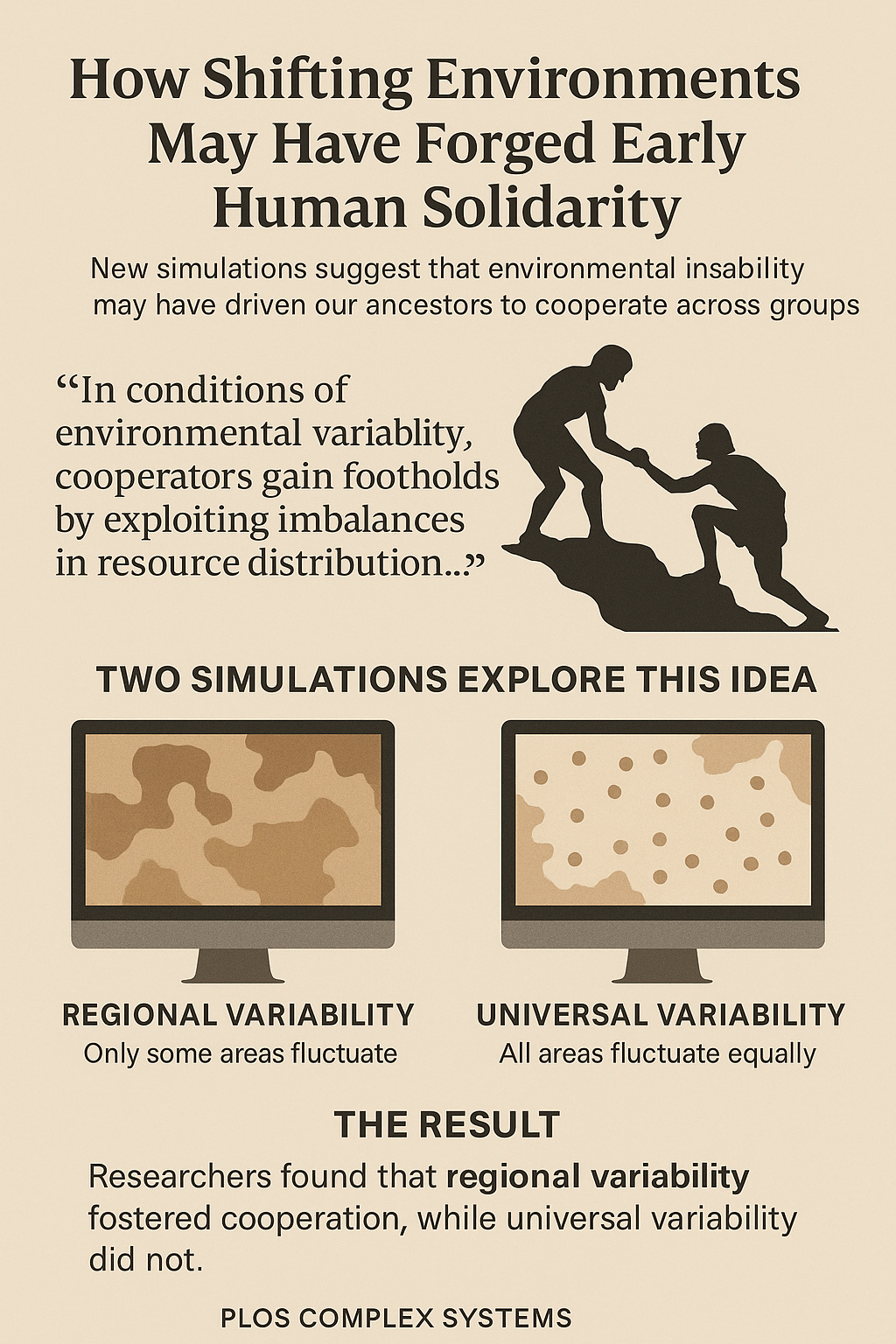

Using multi-agent simulations set across virtual regions experiencing differing degrees of environmental volatility, the researchers constructed two key models:

Regional variability – where some areas were stable while others were unpredictable.

Universal variability – where all areas experienced similar shifts.

Their results point to a striking conclusion. When different regions varied independently—when some were flush with resources and others were destitute—cooperation thrived. This allowed individuals or groups in harsher regions to form cooperative strategies to survive, often gaining from indirect reciprocity or inter-group sharing.

“In conditions of regional environmental variability,” the authors note, “cooperators gain footholds by exploiting imbalances in resource distribution, establishing niches in areas where defection would otherwise dominate.”

In contrast, when environmental stress hit all areas equally (universal variability), cooperation floundered. With no safe zones and no favorable gradients, cooperation provided few immediate benefits and no long-term security.

This nuanced conclusion reframes how archaeologists might look at the social behavior of early humans, especially in Africa between 300,000 and 50,000 years ago—a period marked by extreme climate swings, as seen in geological records from Lake Malawi and marine cores from the Horn of Africa.

Implications for the Evolution of Sociality

The authors connect their findings to a broader theoretical framework: cooperation isn't a luxury of abundance; it’s a strategy for managing scarcity. In contexts where risk and resource unpredictability are unevenly distributed across space, sociality can be a hedge against extinction.

That idea fits with archaeological observations from the African MSA. Artifacts from sites like Blombos Cave in South Africa and Olorgesailie in Kenya suggest complex behaviors—ochre use, shell bead production, long-distance obsidian transport—that imply trust, planning, and collaboration across groups.

This aligns with the growing body of work tying environmental instability to behavioral innovation. In periods of environmental stress, humans didn’t just react—they adapted socially. They may have shared tools, joined forces on hunting expeditions, or formed kin networks across landscapes fragmented by climate oscillations.From Prehistory to Policy

Although grounded in deep time, the implications extend to the present. Inaba and Akiyama suggest that modern societies facing global-scale variability—climate change, pandemics, geopolitical shifts—could benefit from understanding how cooperation emerged in the past. Instead of viewing large-scale crises as times of fragmentation, their model implies such moments might enable collaborative behavior, given the right structural incentives.

“Our findings,” the researchers write, “highlight the importance of asymmetries in risk and opportunity in fostering cooperative strategies—not just in prehistory, but in contemporary policy contexts.”

The takeaway? Cooperation is not an evolutionary accident that emerged during tranquil times. It may be one of the most durable legacies of chaos.

Related Research

Potts, R. (1996). Evolution and environmental change in early human prehistory. Current Anthropology, 37(S1), S1–S38.

https://doi.org/10.1086/204472Brooks, A. S., Yellen, J. E., et al. (2018). Long-distance stone transport and pigment use in the Middle Stone Age of southern Africa. Science, 360(6384), 90–94.

https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao2646Foley, R. (1999). The evolutionary consequences of lateral and temporal variation in climatic and ecological conditions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 354(1379), 1957–1965.

https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1999.0537Stiner, M. C., & Kuhn, S. L. (2006). Changes in the "connectedness" and resilience of Paleolithic societies in Mediterranean ecosystems. Human Ecology, 34(4), 693–712.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-006-9029-0Wadley, L. (2015). Those marvellous millennia: the Middle Stone Age of southern Africa. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa, 50(2), 155–226.

https://doi.org/10.1080/0067270X.2015.1039236

Inaba, M., & Akiyama, E. (2025). Environmental variability promotes the evolution of cooperation among geographically dispersed groups on dynamic networks. PLOS Complex Systems, 2(4), e0000038. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcsy.0000038

Share this post