At first glance, Tel Shiqmona appears unassuming—a rocky outcrop overlooking the Mediterranean just south of modern-day Haifa. But beneath its surface, archaeologists have found what may be the most robust evidence yet of a long-standing, industrial-scale dye production facility operating between 1100 and 600 BCE. Not for clay, copper, or olive oil, but for something far more elusive: color.

And not just any color.

Purple, long a marker of prestige in the ancient Mediterranean, wasn’t merely an aesthetic choice. In the Iron Age, wearing Tyrian purple was often a sign of political power, spiritual authority, or dynastic wealth. Now, a team of archaeologists, chemists, and historians has traced that power to a gritty workshop where craftspeople crushed marine snails, fermented their innards, and produced one of the most expensive pigments of the ancient world.

“This is the first time we’ve been able to document half a millennium of continuous, large-scale production of mollusk-based purple dye in a single place,”

said Golan Shalvi, lead author of the study and director of excavations at the University of Haifa’s Zinman Institute of Archaeology.

The findings, published in PLOS ONE1, reframe how archaeologists understand Iron Age economies—not just as agricultural or military engines, but as specialized manufacturing hubs deeply embedded in regional politics and global trade.

A Color Born from Rot

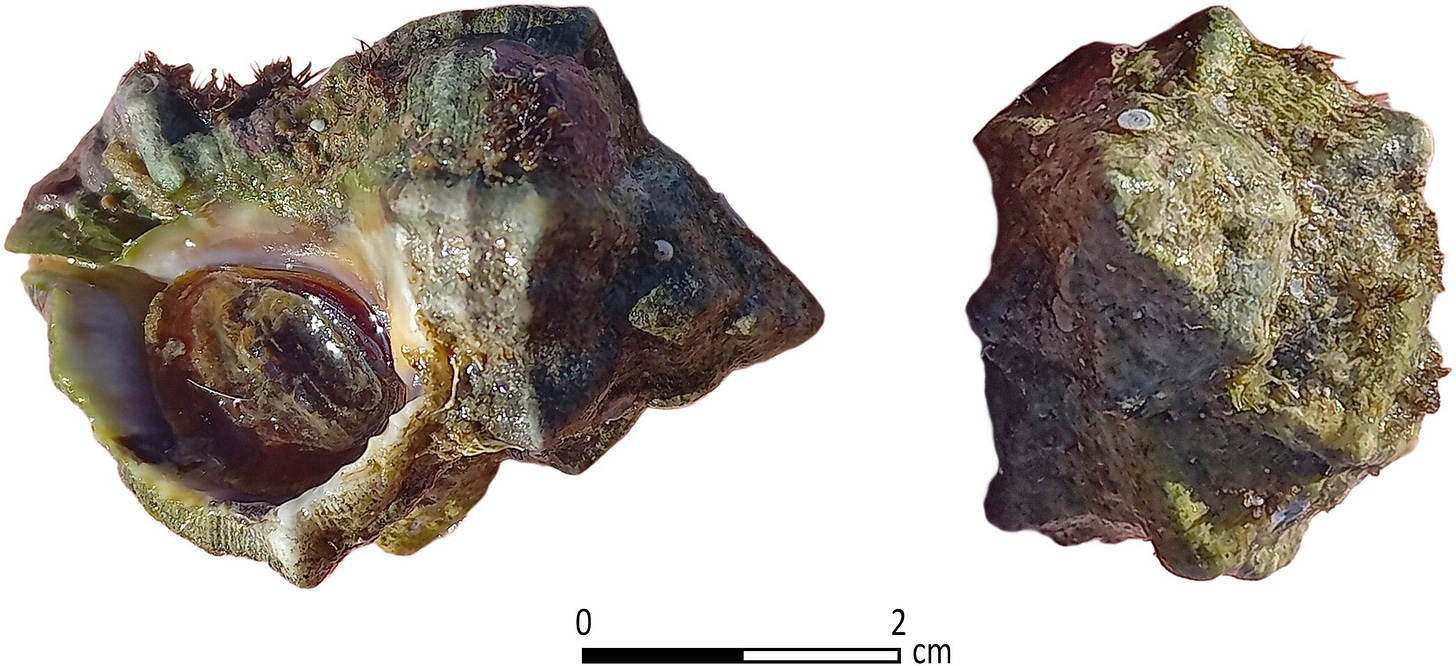

Tyrian purple doesn’t come easily. The dye is made from the hypobranchial gland of several Mediterranean sea snails—Hexaplex trunculus, Bolinus brandaris, and Stramonita haemastoma. Extracting the dye requires not only killing hundreds of snails per gram of pigment, but also a precise fermentation process that includes controlled exposure to air and, sometimes, heat. The gland’s secretion starts off green and only turns purple upon oxidation, a transformation as magical as it is malodorous.

Despite its historical fame, few sites have offered clear evidence of where and how this dye was produced. Shell middens and colored sherds have turned up sporadically across the Levant and Aegean, but Shiqmona is the first place where an entire purple dye facility—vats, tools, architecture, and residue—has been found and contextualized within a diachronic archaeological record.

“What we see at Shiqmona is more than sporadic shell processing. It’s a vertically integrated dye production complex, sustained over centuries,” said Ayelet Gilboa, co-author and senior archaeologist at the University of Haifa.

A City That Smelled of Snails

Shiqmona was no sleepy fishing village. Excavations show the site housed a series of workshops, each with massive clay vats, some over 70 centimeters wide, many stained with a deep purple band where oxidized dye once sloshed. Chemical analyses confirmed the pigment’s origin from Hexaplex trunculus.

The site yielded over 175 artifacts connected to dye manufacture: vat fragments, crushed shells, grinding stones, and purple-streaked potsherds. Many of these were found inside buildings—contrary to long-held assumptions that the smell of rotting snails would have pushed production outside settlement walls.

“There’s been a myth in the literature that these dye facilities were remote or hidden. But Shiqmona shows the opposite. The industry was part of the built environment,” said Shalvi. “This was a place of work, noise, and probably a lot of smell—but also expertise.”

Some of the vats were large enough to hold 350 liters of fluid. Based on ceramic petrography, they were made locally with coastal clay rich in foraminiferal chalk and marine microfauna—fabrics specific to the Carmel coast.

Craft and Power in the Iron Age Levant

Shiqmona’s industrial output waxed and waned with political fortunes. Production ramped up in the 9th century BCE, coinciding with the rise of the northern Kingdom of Israel. Later, during Assyrian occupation, the site flourished again. When the Babylonians sacked the region in the 6th century BCE, production stopped—and so did the occupation of Shiqmona.

The site’s stratigraphy mirrors larger historical arcs, suggesting that purple dye wasn't merely a luxury good but also a node in a larger economic and symbolic system.

“This dye wasn’t just for elites—it helped create elites,” said Naama Sukenik, an Israel Antiquities Authority expert on ancient textiles. “Access to and control over this kind of production would have reinforced status in both secular and ritual spheres.”

What the Snails Still Tell Us

Today, the same rocky reef that once hosted abundant Muricidae is a marine nature preserve. The mollusks have declined across the Mediterranean, stressed by pollution and warming seas. But on calm days, divers still spot them clinging to the rocks near Shiqmona—biological ghosts of an industry that shaped empires.

Modern analysts aren’t just mining color from the past. They’re reconstructing how ancient people organized labor, managed marine resources, and produced craft knowledge over generations. In the process, they're sketching a more complete picture of what it meant to be a node in the ancient global economy—not just for kings, but for craftspeople.

Related Research

Sukenik, N., et al. (2021). “Late Bronze and Iron Age textiles from the Southern Levant and the dyeing technologies they reflect.” Antiquity, 95(383), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2021.30

Mylona, D. (2013). “Purple-dye production in the Aegean: archaeological, historical and ethnographic approaches.” In The Aegean and its Cultures (eds. Galanaki et al.). INSTAP Academic Press.

Koren, Z. C. (2005). “High-performance liquid chromatography of royal purple dye in ancient textiles.” Journal of Archaeological Science, 32(3), 417–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2004.11.005

Shalvi, G., et al. (2025). “Tel Shiqmona during the Iron Age: A first glimpse into an ancient Mediterranean purple dye ‘factory.’” PLOS ONE, 20(4), e0321082. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0321082

Shalvi, G., Sukenik, N., Waiman-Barak, P., Dunseth, Z. C., Bar, S., Pinsky, S., Iluz, D., Amar, Z., & Gilboa, A. (2025). Tel Shiqmona during the Iron Age: A first glimpse into an ancient Mediterranean purple dye ‘factory.’ PloS One, 20(4), e0321082. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0321082

Share this post