When the last Ice Age released its grip on northern Europe, vast landscapes emerged from the ice. Among them was a rugged, newly exposed frontier—the British Isles. While the southern lowlands began to host reindeer hunters and mobile foragers, the highlands and islands of Scotland remained largely uncharted in the archaeological record. Until now.

A new study in the Journal of Quaternary Science1 suggests that at least one band of Late Upper Paleolithic foragers made their way to the windswept tip of the Isle of Skye, a place so remote it has long been considered beyond the reach of early postglacial settlement. Their toolstone traces—small but significant—point toward a likely Ahrensburgian presence in northwestern Scotland around 11,000 years ago.

A surprising find on the edge of Europe

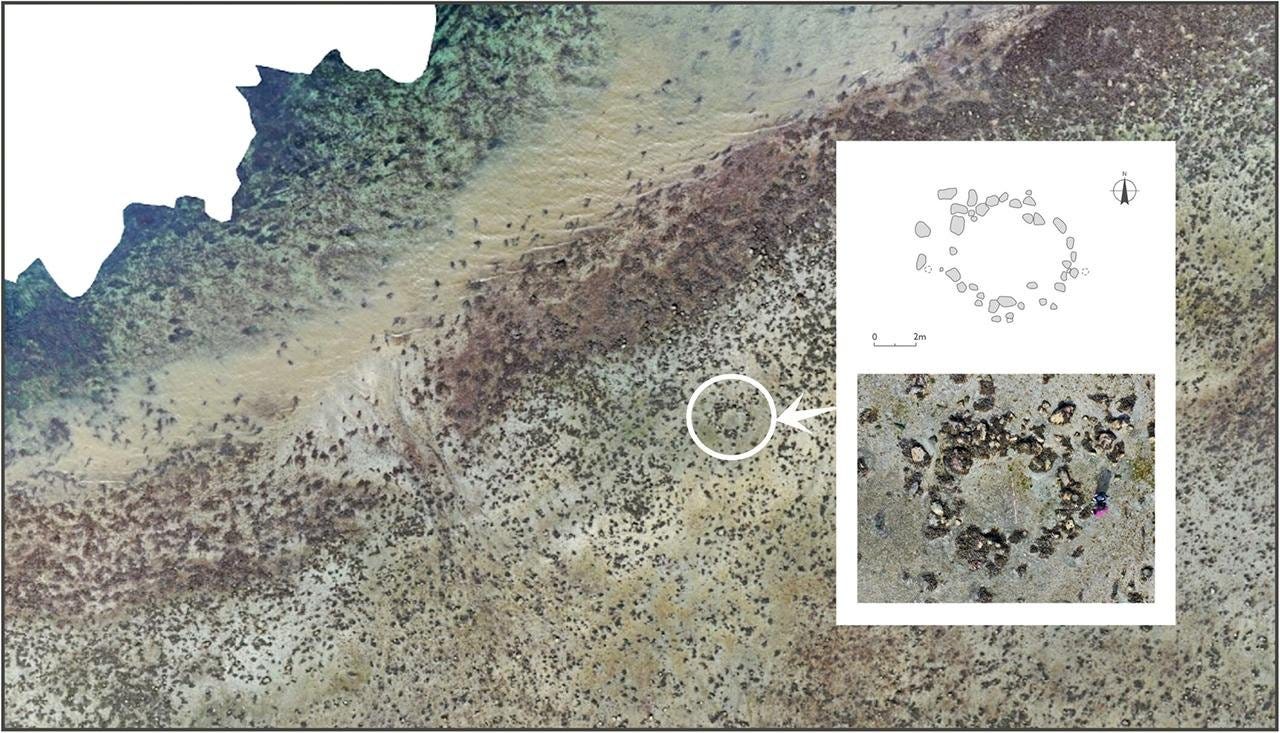

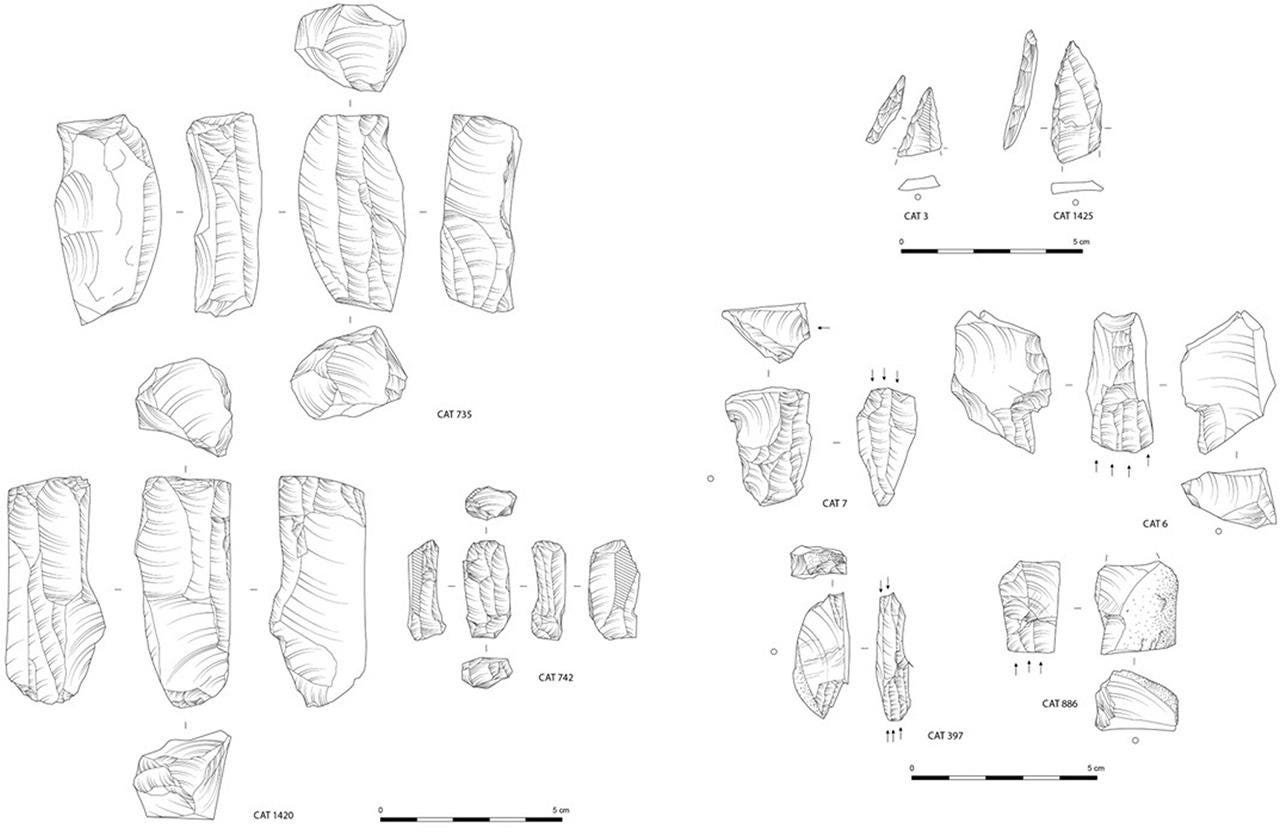

The site in question lies at the far northern end of Skye, in a landscape carved by retreating glaciers and shaped by Atlantic storms. Lithic artifacts recovered during recent surveys—specifically tanged points, backed bladelets, and other microliths—match the technological signature of the Ahrensburgian tradition, which spread across northern Europe in the terminal Pleistocene.

The Ahrensburgian culture is best known from the North European Plain, where hunter-gatherers adapted to the cold, open tundra with a specialized hunting toolkit aimed at reindeer. Their presence in mainland Britain has long been debated. Evidence has trickled in from sites in Yorkshire and Kent, but Skye, until now, was off the archaeological map.

“These are not Mesolithic microliths,” says Karen Hardy, lead author of the study. “They’re tanged points, indicative of an Ahrensburgian horizon, likely brought by groups moving along the coast as the ice retreated and sea levels changed.”

The timing aligns with a narrow climatic window at the end of the Younger Dryas, when cold adapted species—and the humans who followed them—had a brief final foothold in northern Britain before Holocene warming and sea-level rise transformed the landscape.

A land bridge lost to the sea

One of the study’s most compelling arguments rests on the paleogeography of the North Atlantic shelf. During the Late Glacial period, sea levels were much lower than today. The Inner Hebrides, including Skye, were not isolated islands, but part of an expansive coastal plain that extended far west into what is now submerged under the sea.

These conditions would have made coastal migration possible—and even practical—for reindeer and humans alike. As glaciers receded, herbivores expanded into new pastures, drawing hunters behind them.

“We must consider not only what is visible today,” Hardy notes, “but also what has been lost to the sea. The edge of everything then was not where it is now.”

As sea levels rose in the early Holocene, these low-lying corridors were gradually drowned, erasing a vital chapter of human movement. What remains are scattered clues—like the artifacts on Skye—that hint at deeper stories.

Minimal evidence, maximal implications

Skepticism is natural when dealing with such fragmentary finds. The lithic assemblage from Skye is small, and no bone or organic remains have survived to provide radiocarbon dates. But the tool forms and stratigraphic context match known Late Glacial typologies. The study leans on comparative typology, technological analysis, and landscape modeling to build its case.

Importantly, this site adds to a growing body of evidence that Late Upper Paleolithic peoples were more mobile and more widespread in Britain than previously assumed. And it reinforces the idea that coastal and insular zones—often marginalized in reconstructions of early prehistory—may have played pivotal roles in human dispersals.

Rewriting Britain’s Late Glacial map

The suggestion of an Ahrensburgian presence in Skye challenges longstanding narratives that confine Late Upper Paleolithic activity to southern England. Instead, it points to dynamic forager lifeways adapted not only to the continent's interior but also to its shifting coasts and island fringes.

This discovery, modest in size but bold in implication, helps reframe the final chapters of Ice Age human history in the British Isles.

“At the far end of everything,” the study’s authors write, “there were people.”

And they left behind not grandeur, but fragments—a chipped blade here, a broken tang there. Enough to glimpse the long-forgotten routes taken by the hunters who ventured, briefly, to the cold margins of the world.

Suggested Related Research

Grimm, S. B., & Weber, M.-J. (2008). The chronostratigraphy of the Late Paleolithic Federmesser-Gruppen complex: A re-evaluation. Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt, 38(1), 1–28.

Barton, R. N. E., Roberts, A. J., & Roe, D. A. (1991). The Late Glacial in north-west Europe: Human adaptation and environmental change at the end of the Pleistocene. CBA Research Report 77. https://doi.org/10.5284/1000335

Conneller, C., & Schadla-Hall, R. (2003). Beyond Star Carr: The Vale of Pickering in the tenth millennium BP. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 69, 85–105. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0079497X00001128

Hardy, K., Barlow, N. L. M., Taylor, E., Bradley, S. L., McCarthy, J., & Rush, G. (2025). At the far end of everything: A likely Ahrensburgian presence in the far north of the Isle of Skye, Scotland. Journal of Quaternary Science. https://doi.org/10.1002/jqs.3718

Share this post