When archaeologists sift through the remains of ancient settlements, they are not just uncovering lost homes—they are mapping the roots of inequality. Long before pharaohs ruled and scribes recorded human affairs, the seeds of economic disparity had already taken hold.

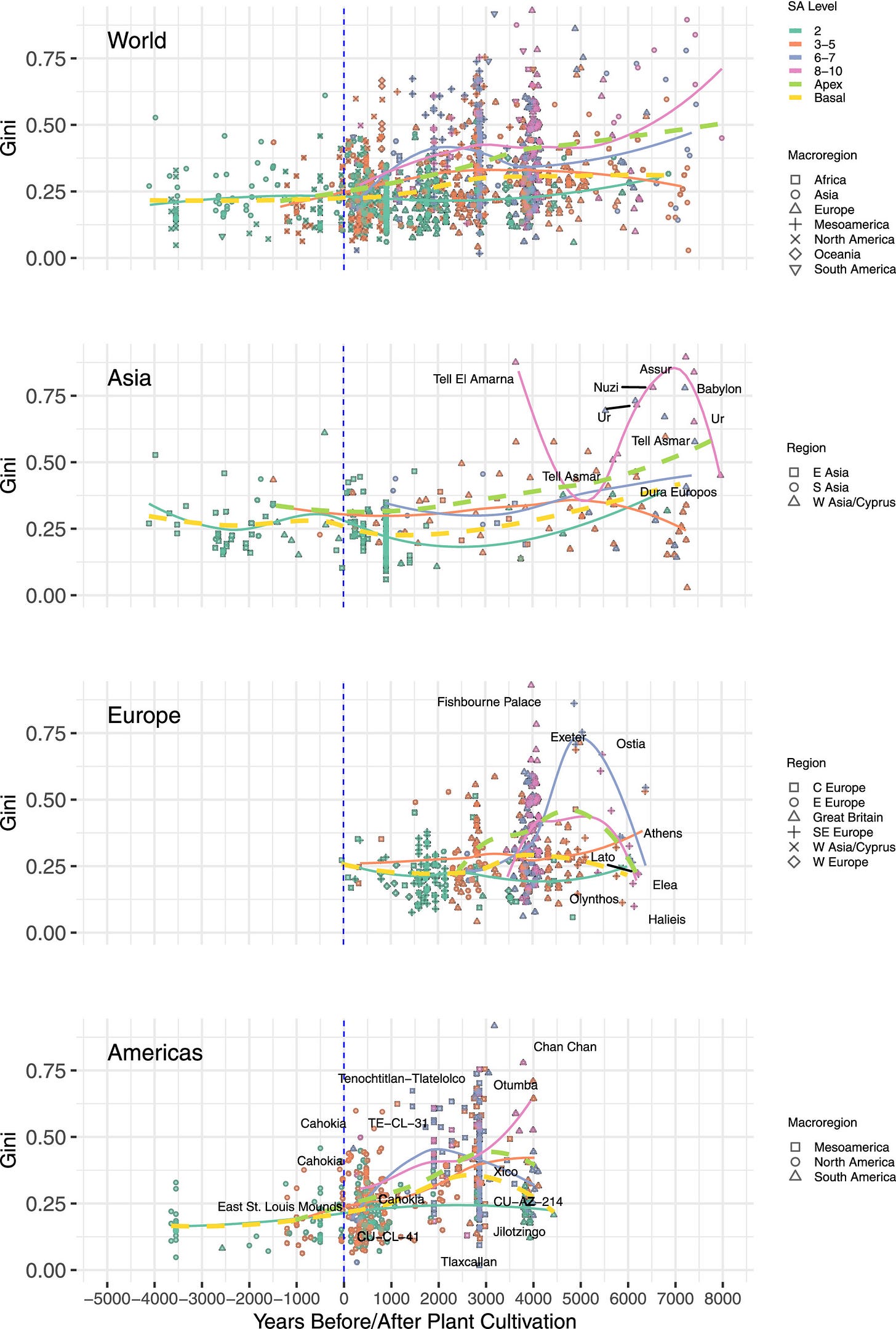

In a sweeping new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences1, an international team analyzed the size of more than 47,000 houses across 1,100 archaeological sites. Their conclusion is clear: wealth inequality is not a modern invention, nor did it arise only with the rise of kings or written law. It grew slowly, subtly, and globally alongside agriculture.

“Many people imagine early societies as egalitarian,” notes archaeologist Tim Kohler of Washington State University.

“But the data show that wealth inequality took root surprisingly early.”

Measuring Inequality in Mudbrick and Stone

The researchers turned to one of the most consistent archaeological indicators of wealth: house size. Larger houses, they argue, reflect not only more living space but also access to better materials, skilled labor, and prime land. By applying the Gini coefficient—a widely used metric for measuring inequality—to house sizes, the study created a cross-cultural snapshot of economic disparity over 10,000 years.

The results were nuanced. Small farming communities that emerged shortly after the advent of agriculture tended to be more equal. But as populations grew and settlements became more complex, disparities widened.

“The shift wasn’t instantaneous,” says Kohler.

“It grew gradually as societies expanded, populations increased, and resources became more constrained.”

When Land Becomes Power

Agriculture brought abundance, but it also brought limits. Once people stopped moving and began farming fixed plots of land, ownership and inheritance began to matter. In densely populated settlements, the competition for arable land likely created winners and losers.

Some families built terraces or dug irrigation canals to make the most of their land—innovations that increased productivity but also required labor, tools, and cooperation. Over time, these advantages accumulated, and so did inequality.

The emergence of hierarchical settlements, where elites lived in larger, more elaborate dwellings near central public buildings, reflected not just economic advantage but also political power. Inequality, the study suggests, was both a product and a driver of early social complexity.

Technology: A Double-Edged Trowel

Not all innovations favored the powerful. Iron tools, for example, often had an equalizing effect. By making high-quality implements more widely available, iron smelting may have helped reduce inequality in some societies. This contradicts the common belief that technological change always benefits elites first.

Governance also played a role. In some regions, communal institutions or redistribution systems may have dampened inequality, allowing large societies to grow without extreme economic disparity.

“There are factors that may increase inequality,” Kohler notes.

“But these factors can be leveled off or modified by different human decisions and institutions.”

A Prehistory of Possibilities

The study’s findings challenge the assumption that inequality is inevitable once societies become large and complex. The archaeological record, stretching across six continents and 10 millennia, shows otherwise. Inequality is not a default state of civilization—it is a historical process shaped by choices, constraints, and cultural norms.

This research, conducted in collaboration with 27 scholars and the Coalition for Archaeological Synthesis, offers more than historical insight. It reminds us that inequality has always been negotiable.

“Although history has shown us that technology and population growth can raise the potential for inequality,” Kohler says,

“people have implemented systems that mute that potential.”

In a world where economic divides continue to widen, the past may hold not only cautionary tales but also strategies for balance.

Related Research

Here are additional studies that connect or expand on this research:

Feinman, G. M., et al. (2025).

Assessing grand narratives of economic inequality across time.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 122(16).

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2400698121Kohler, T. A., et al. (2017).

Greater post-Neolithic wealth disparities in Eurasia than in North America and Mesoamerica.

Nature, 551(7682), 619–622.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nature24646Scheidel, W. (2017).

The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century.

Princeton University Press.

Link to publisherSmith, M. E., & Peregrine, P. N. (2012).

Comparative Archaeology: A Framework for Analysis.

Springer.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-6520-0

Kohler, T. A., Bogaard, A., Ortman, S. G., Crema, E. R., Chirikure, S., Cruz, P., Green, A., Kerig, T., McCoy, M. D., Munson, J., Petrie, C., Thompson, A. E., Birch, J., Cervantes Quequezana, G., Feinman, G. M., Fochesato, M., Gronenborn, D., Hamerow, H., Jin, G., … Pailes, M. (2025). Economic inequality is fueled by population scale, land-limited production, and settlement hierarchies across the archaeological record. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 122(16). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2400691122

Share this post