The Energy Revolution: How Humans Became Metabolic Outliers in Evolution

A Harvard study reveals humans’ uniquely high metabolic rates as a key driver of our evolution, brain development, and reproductive success.

Redefining Human Energy

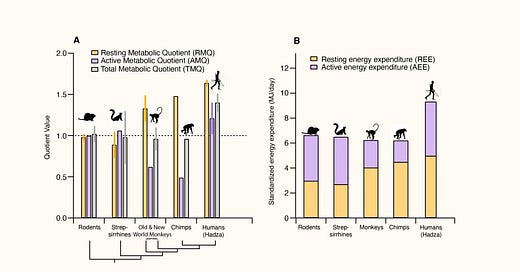

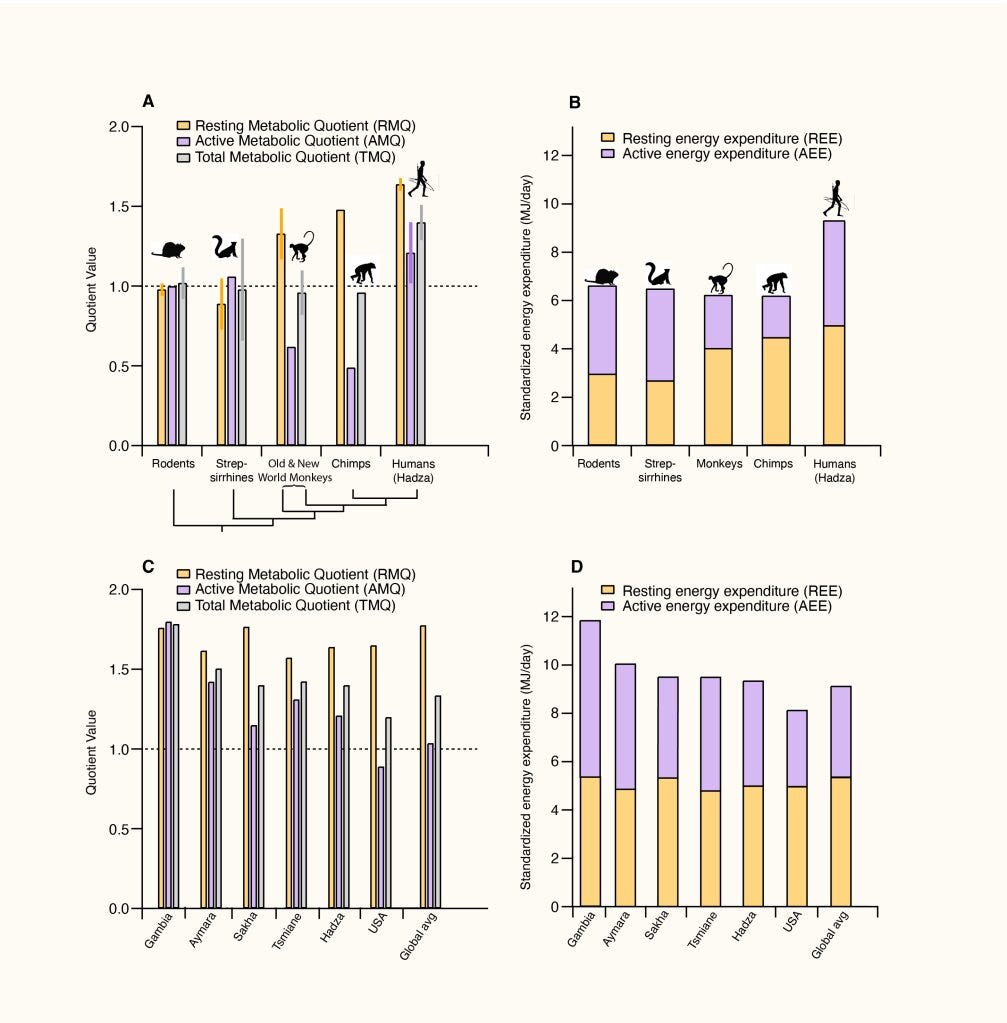

Humans are remarkably different from other mammals, including our closest relatives like chimpanzees, when it comes to energy use. A groundbreaking study by Harvard researchers, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences1, finds that humans exhibit exceptionally high metabolic rates—both at rest and during physical activity. This unique energy expenditure played a pivotal role in enabling the evolution of larger brains, extended lifespans, and greater reproductive success, setting humans apart in the animal kingdom.

Metabolism as an Evolutionary Driver

Metabolism is the process through which organisms convert food into energy to fuel vital functions. In most animals, this energy is allocated between two primary categories: resting metabolic rate (RMR) and active metabolic rate (AMR). However, a distinct tradeoff exists—species that allocate more energy to resting functions, such as maintaining body heat and supporting the brain, tend to exhibit lower physical activity levels.

Chimpanzees, for example, expend significant energy on their large brains and long lifespans, resulting in high RMR. However, this comes at the cost of reduced physical activity.

“Chimpanzees, with their large brains, costly reproductive strategies, and lifespans, are couch potatoes who spend much of their day eating,” explained Daniel Lieberman, co-author and paleoanthropologist at Harvard.

Humans, by contrast, have evolved a striking ability to escape this tradeoff.

Humans Break the Rules of Energy Allocation

Unlike other primates and mammals, humans have increased both resting and active metabolic rates. This remarkable adaptation allows humans to sustain high-energy activities without compromising vital resting functions.

“Humans have increased not only our resting metabolisms beyond what even chimpanzees and monkeys have,” said co-author Andrew Yegian, “but—thanks to our unique ability to dump heat by sweating—we’ve also been able to increase our physical activity levels without lowering our resting metabolic rates.”

This heat-dumping ability, enabled by our specialized sweat glands, is a critical factor in allowing humans to remain active in warm environments. This combination of elevated RMR and AMR makes humans an “energetically unique species.”

Quantifying the Human Metabolic Edge

Using advanced analytical methods that correct for body size, environmental temperature, and body fat, the research team discovered:

Non-human primates, such as chimpanzees, invest 30–50% more calories in their RMR compared to other mammals of similar size.

Humans take this to the extreme, expending 60% more calories than comparable mammals.

“We started off questioning if it was possible that humans and other primates could have comparatively low total metabolic rates,” Yegian noted. “That’s when we hit the accelerator.”

This elevated caloric investment in RMR supported the development of large brains and extended lifespans, allowing early humans to thrive in diverse environments.

The Evolutionary Advantage of Activity

In other mammals, high resting metabolism often limits physical activity due to the challenges of heat dissipation. For instance, chimpanzees, living in tropical climates, reduce activity to avoid overheating.

Humans overcame this limitation by evolving a more efficient thermoregulation system, which allows for high levels of physical activity while maintaining elevated resting metabolic functions. This adaptation was essential for early hunter-gatherers, who needed the energy for tasks like long-distance foraging, tool-making, and social cooperation.

Metabolism Across Human Populations

While humans share a baseline of elevated RMR, variations exist in activity levels between populations. For example, subsistence farmers, who grow their food without mechanized tools, demonstrate higher physical activity levels than hunter-gatherers or industrialized populations. Despite this, their RMR remains consistent with other humans.

“What we’re really interested in is variation among humans in metabolic rates,” said Yegian, “especially in today’s world of increasing technology and lower levels of physical activity.”

The study raises questions about how modern sedentary lifestyles, characterized by desk jobs and minimal physical exertion, impact metabolism and overall health.

Implications for Modern Health

Humans evolved to be active, with high metabolic rates supporting both physical and cognitive demands. As modern technology reduces the need for physical activity, the mismatch between our evolutionary biology and contemporary lifestyles poses significant health risks. Sedentary habits could disrupt metabolic balance, potentially leading to issues such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic disorders.

Further research into metabolic variation among human populations may offer insights into optimizing health in a rapidly changing world.

Yegian, A. K., Heymsfield, S. B., Castillo, E. R., Müller, M. J., Redman, L. M., & Lieberman, D. E. (2024). Metabolic scaling, energy allocation tradeoffs, and the evolution of humans’ unique metabolism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 121(48). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2409674121