The Evolutionary Puzzle of Sexual Dimorphism in Early Hominins

How Male and Female Differences Complicate the Hominin Fossil Record

Sexual dimorphism—the physical differences between males and females of a species—has long been a defining feature of primates, shaping their social structures, reproductive strategies, and even survival tactics. But for paleoanthropologists trying to sort out the tangled branches of the human family tree, these differences can cause major taxonomic headaches.

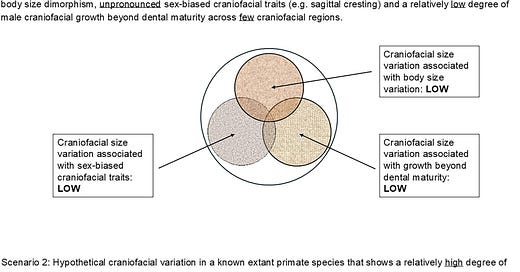

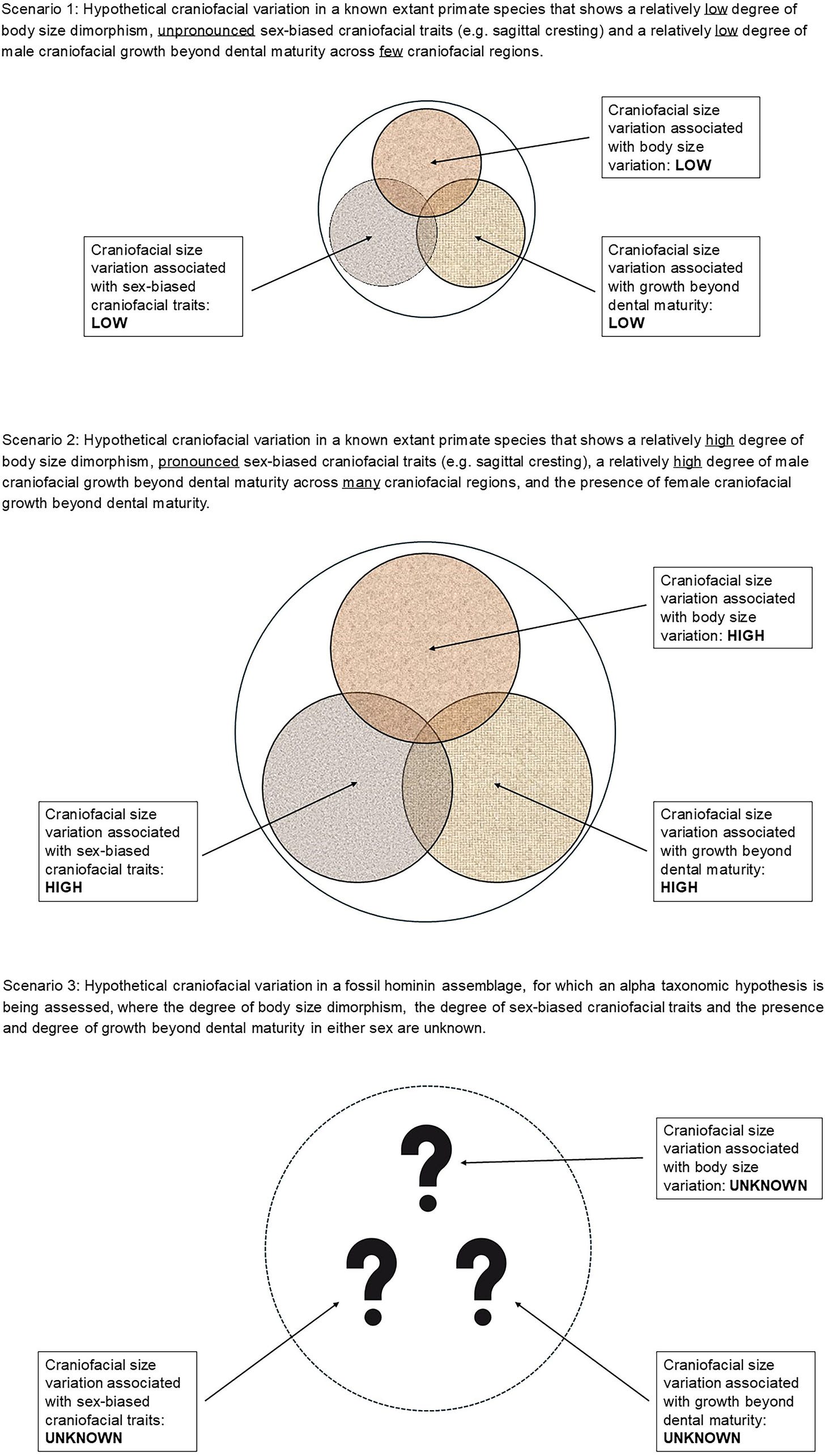

A new study published in Evolutionary Anthropology1 examines how skeletal dimorphism in early hominins, particularly in the genus Paranthropus, may be distorting species classification. The authors argue that traits shaped by sexual selection—such as body size, facial structure, and cranial crests—should be carefully scrutinized before being used to define new species.

"High levels of sexual dimorphism, and the associated intra-specific variation, render certain skeletal regions especially unreliable for generating alpha taxonomic hypotheses," the study states.

These findings challenge some long-standing assumptions about the diversity of early hominins and suggest that what may look like different species could, in some cases, be just male and female variants of the same species.

The Challenge of Identifying Species in the Fossil Record

Fossils do not come with a label indicating whether they belonged to a male or a female, making it difficult to determine whether variations within a set of fossils represent different species or simply the natural differences between sexes.

For instance, Paranthropus boisei, one of the most robust hominins known from the Pleistocene, exhibits extreme craniofacial variation. Some skulls, like the famous OH 5 specimen, have massive jaws and prominent sagittal crests, while others have smaller, less pronounced features. Some researchers have suggested that this variation reflects separate species, but others argue it is simply sexual dimorphism at play.

The study authors caution against using certain skeletal traits, particularly those influenced by sexual selection, to define new species. These include brow ridges, sagittal crests, and facial prognathism—features that are known to vary dramatically between males and females in many primate species.

"Regions of the skeleton that are hypothesized to vary in response to sexual or social selection among hominins should be avoided when generating alpha taxonomic hypotheses," the researchers note.

What Drives Sexual Dimorphism in Primates?

In modern primates, sexual dimorphism is closely tied to social structures. In species where males compete intensely for mates, such as gorillas, males tend to be much larger than females and develop secondary sexual characteristics, like sagittal crests and enlarged canines, that serve as signals of dominance.

The same pattern is seen in the fossil record of early hominins. For example, some researchers argue that Australopithecus afarensis—the species that includes the famous "Lucy" skeleton—shows a level of size dimorphism comparable to modern gorillas. If true, this suggests a mating system where dominant males had access to multiple females, similar to gorilla harems today.

However, not all hominins followed this pattern. Homo species, including Homo erectus, show a reduction in sexual dimorphism, suggesting a shift toward more cooperative social structures. This transition may have coincided with changes in diet, tool use, and the development of pair-bonding behaviors.

Rethinking the Hominin Family Tree

The implications of this research extend beyond classification. If some species have been misidentified due to sexual dimorphism, then our understanding of hominin diversity may need revision. Some taxa that have been considered separate species could, in fact, be male and female versions of the same group.

This is particularly relevant for the Paranthropus lineage. The study suggests that fossils attributed to P. boisei and P. robustus may not represent two separate species, but instead reflect regional or sex-based differences within a single lineage.

The debate over how to classify early hominins is unlikely to be settled anytime soon. But by refining methods for distinguishing between species and individual variation, paleoanthropologists are taking steps toward a clearer picture of human evolutionary history.

"Appreciating the nature and extent of sexual dimorphism in the hominin fossil record is essential if we are to generate sound alpha taxonomic hypotheses," the study concludes.

Related Research

If you're interested in exploring this topic further, here are some additional studies on sexual dimorphism and hominin taxonomy:

Lieberman, D. E., Pilbeam, D. R., & Wood, B. A. (1988). "A Probabilistic Approach to the Problem of Sexual Dimorphism in Homo habilis: A Comparison of KNM‐ER 1470 and KNM‐ER 1813." Journal of Human Evolution, 17(5), 503–511.

Plavcan, J. M. (2000). "Inferring Social Behavior From Sexual Dimorphism in the Fossil Record." Journal of Human Evolution, 39, 327–344.

Wood, B., & Constantino, P. (2007). "Paranthropus boisei: Fifty Years of Evidence and Analysis." American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 134, 106–132.

Balolia, K. L., & Wood, B. (2025). "Comparative Context of Hard‐Tissue Sexual Dimorphism in Early Hominins: Implications for Alpha Taxonomy." Evolutionary Anthropology, 34(1), e22052.

Balolia, K. L., & Wood, B. (2025). Comparative context of hard-tissue sexual dimorphism in early hominins: Implications for alpha taxonomy. Evolutionary Anthropology, 34(1), e22052. https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.22052