An Ancient Practice, Revisited Through Code

Knots are one of humanity’s oldest tools—so ancient, in fact, that they predate agriculture, metallurgy, and written language. But beyond their everyday function of fastening and securing, knots hold something deeper: a story about the evolution of human cognition, the flow of culture, and the quiet persistence of shared technique across continents and millennia.

In a new study published in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal1, researchers from institutions across Europe compiled the most comprehensive cross-cultural knot database to date. By analyzing 338 distinct knots from archaeological archives and museum collections, they discovered a surprisingly stable repertoire. Despite differences in time, geography, and material culture, many human groups developed the same set of knots—again and again.

“The world over, people tend to make the same set,”

— Felix Riede, Aarhus University

This consistency raises important questions: Are these knots the result of cultural diffusion, convergent evolution, or something even more fundamental—like the shape of human cognition?

Encoding Entanglement—How Math Helped Map Knots

Knots rarely survive in the archaeological record. Cordage decays, and with it, the chance to observe how ancient people tied, bundled, or carried their world. Yet the challenge wasn't just finding knots—it was categorizing them in a way that could reveal patterns across space and time. For that, the team borrowed a technique from an unexpected source: knot theory.

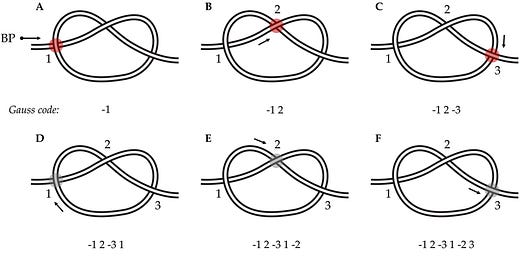

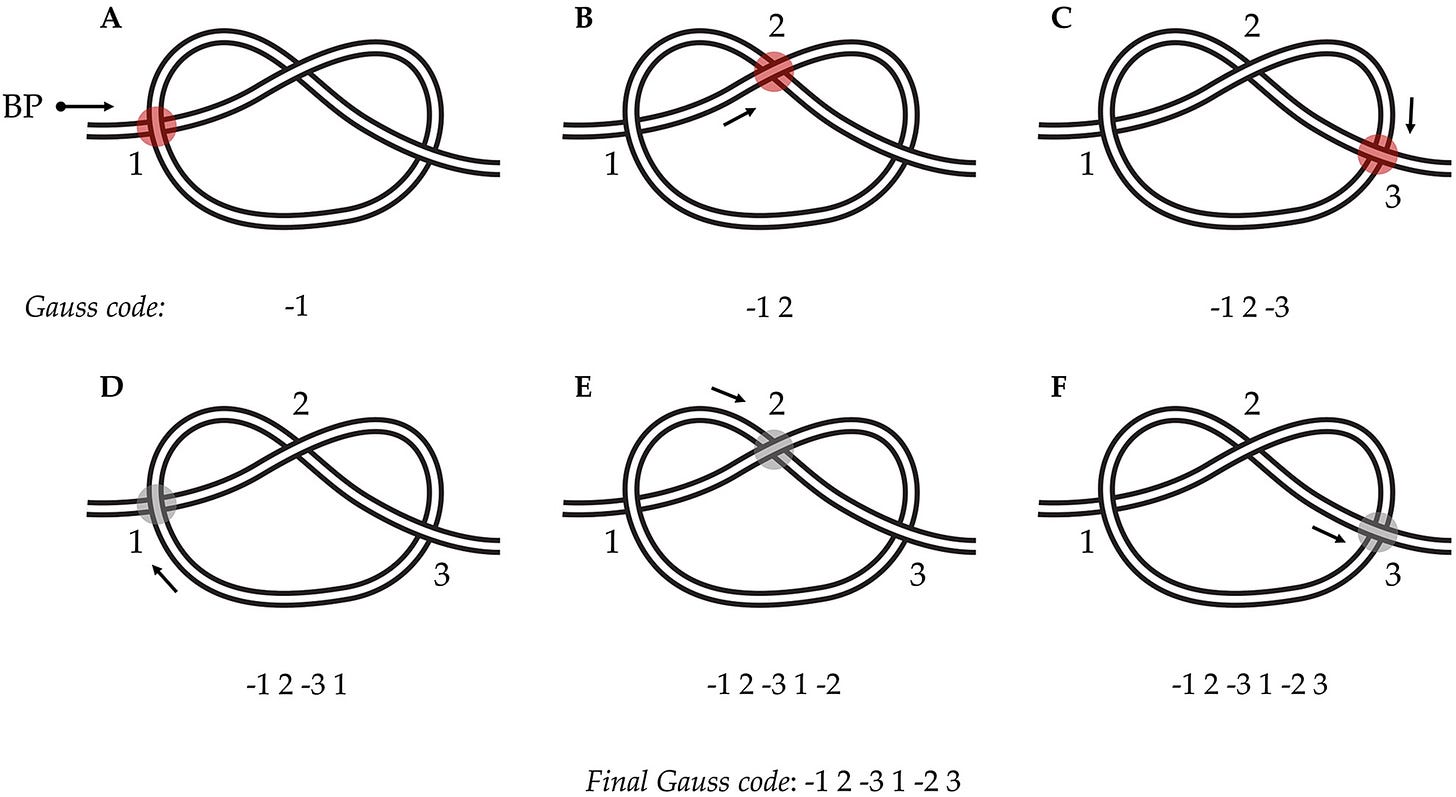

Using a mathematical approach known as Gauss coding, the researchers created a digital fingerprint for each knot. This code maps the crossing points of the rope—labeling over-crossings as positive and under-crossings as negative—allowing each knot to be represented as a sequence of integers.

“We simply recorded all knots we could find,”

— Roope Kaaronen, University of Helsinki

Once coded, the team used clustering algorithms to group similar knots based on shared sub-sequences—akin to comparing DNA by the similarity of gene sequences. The result was a phylogenetic-style tree, revealing which knots had common structural "ancestors" and where certain forms independently reemerged.

From Fiji to Finland—The Global Life of the Sheet Bend

One of the most striking findings was the recurrence of the same knot—the sheet bend—in dozens of contexts. This versatile knot, still used in modern fishing nets and volleyball courts, appeared in the archaeological records of Pacific islands, South America, and even northern Europe.

“The ability to tie them may have been passed between cultures, or more likely through shared ancestry,”

— Roope Kaaronen

But cultural transmission can’t explain everything. In some cases, such as identical knots from South America and Russia, the likelihood of direct interaction is negligible. Instead, the recurrence of the same form points toward convergent innovation—different groups solving the same physical problem in the same way.

This supports a growing hypothesis in cognitive archaeology: that human hands and minds, when faced with similar materials and constraints, tend to arrive at a limited set of functional solutions.

Cognitive Implications—The Algorithm in the Palm

Beyond their utility, knots may tell us something about how early humans thought. The study’s authors suggest that tying a knot requires a kind of "manual algorithm"—a sequence of intentional steps that mirrors abstract reasoning. This could place knotting among the earliest examples of procedural thinking.

“Tying a knot is finger math, if you will,”

— Felix Riede

Evidence from sites like Blombos Cave in South Africa—where 70,000-year-old beads show wear patterns consistent with being strung—suggests that knotting may predate symbolic language and even number systems.

If so, then the act of knotting may have served as a cognitive scaffold, training early humans in the kind of stepwise logic that would later support arithmetic, weaving, and even the syntax of language.

Looking Ahead—A Digital Rosetta Stone for Cordage

This new database doesn’t just rewrite what’s known about prehistoric technology—it gives museums and researchers a digital toolkit to reexamine existing collections. Many knotted artifacts remain tucked away in storage, undocumented and undigitized.

“There are lots of knotted items buried deep in museum archives that we haven’t had any access to,”

— Roope Kaaronen

With Gauss-coded comparisons, curators could match a knot from Fiji to one in Norway and begin to trace networks of influence or independent problem-solving across the globe.

For mathematicians, too, the implications are tantalizing. The study introduces new applications for analyzing so-called "tangles"—knots with loose ends—opening up avenues in both topology and applied computation.

The Knot as Legacy

Knots may be small, but they bind together vast ideas: migration, cognition, and the quiet engineering of daily life. Their persistence across cultures may reflect not just shared ancestry or interaction, but the constraints—and genius—of the human hand.

If early humans puzzled over loops and tension, if they practiced and passed along techniques refined over generations, then perhaps tying a knot wasn’t just a practical act. Perhaps it was also the beginning of something else: abstraction, memory, and meaning made tangible.

Related Research

Tehrani, J. J. (2013). The phylogeny of Little Red Riding Hood. PLOS ONE, 8(11), e78871. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0078871

— Explores cultural phylogenetics through folk narratives, analogous to the methods applied to knot histories.Riede, F. (2011). Adaptation and niche construction in human prehistory: A case study from the southern Scandinavian Late Glacial. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 366(1566), 793–808. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0266

— Discusses how prehistoric humans adapted to environmental pressures, linking cognitive plasticity with technological responses.Henrich, J. (2015). The Secret of Our Success: How Culture Is Driving Human Evolution, Domesticating Our Species, and Making Us Smarter. Princeton University Press.

— Though not a paper, this book provides key theoretical underpinnings about cumulative cultural evolution, relevant to understanding knot standardization.Coolidge, F. L., & Wynn, T. (2009). The Rise of Homo Sapiens: The Evolution of Modern Thinking. Wiley-Blackwell.

— Addresses the cognitive evolution of Homo sapiens, including procedural and spatial reasoning—skills integral to knotting.

Kaaronen, R. O., Henrich, A. K., Manninen, M. A., Walsh, M. J., Wisher, I., Eronen, J. T., & Riede, F. (2025). The ties that bind: Computational, cross-cultural analyses of knots reveal their cultural evolutionary history and significance. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0959774325000071

Share this post