In the shadows of the Beni-Snassen Mountains, tucked into a cave called Taforalt, archaeologists have been piecing together an unexpected story about the rituals of late Pleistocene humans. Not just about who they buried—but what they buried with them. Among the artifacts and bones of those interred are the carefully butchered remains of Otis tarda, the great bustard, a bird that once roamed the open plains of North Africa in numbers.

Now, researchers say1, those bones tell a story not just about a species in decline, but about a species—our own—trying to make meaning of life and death.

A Bird of Ceremony

The great bustard is not an easy bird to ignore. Males can weigh up to 18 kilograms, placing them among the heaviest animals capable of flight. Their courtship displays are as elaborate as their plumage, and their preferred habitat—open grasslands—makes them conspicuous. Today, only a handful survive in Morocco, their population isolated and critically endangered.

But 15,000 years ago, the bird was more than just a presence on the plains. In the archaeological layers of Taforalt, also known as Grotte des Pigeons, researchers have unearthed not only bustard bones, but strong evidence of their ritual use.

“The repeated presence of butchered bustard remains in the graves suggests a deliberate and symbolic act,” said ornithologist Joanne Cooper of the Natural History Museum in London. “It wasn’t casual consumption. These birds were selected and prepared for something more meaningful.”

Ritual Feasting in a Cemetery Cave

The burials at Taforalt are some of the oldest known in Africa, dating back nearly 15,000 years. Dozens of human skeletons have been found there, some seated, some accompanied by grave goods—and, in certain cases, pieces of great bustards.

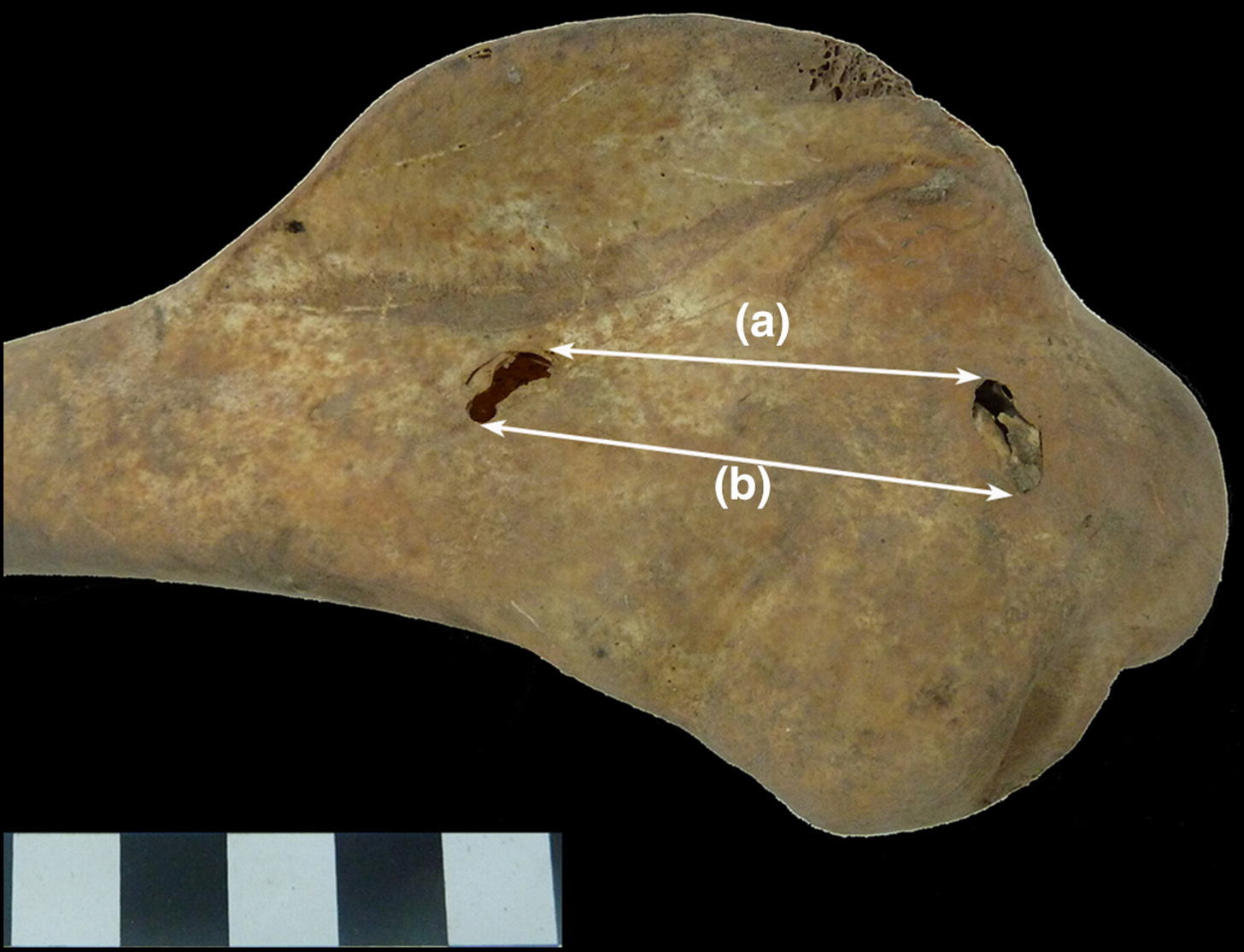

One such grave, identified as Individual 14, contained a large male bustard's sternum, bearing precise cut marks. It was laid beside the human’s legs, likely placed there with intention. Another bustard bone from the cave carries what appears to be a human bite mark—puncture wounds made by upper canines, with no matching indent from the incisors, a detail consistent with the local cultural practice of tooth evulsion.

“The positioning of these remains, and the anatomical locations of the cuts, point to a specific way of processing and consuming the birds,” said Cooper. “It resembles the kind of structured feasting we associate with ritual contexts.”

The birds were not abundant in the mountains surrounding the cave. Early humans would have had to travel across the plains to hunt them, then haul their massive carcasses back up to the burial site. That effort suggests intentionality—a ceremonial behavior involving food, memory, and perhaps, offerings to the dead.

A Cultural Link That Spans Millennia

The evidence from Taforalt does more than document the diet of early North Africans. It helps resolve a long-standing question about the great bustard’s status in the region. Some researchers had argued that the species was a relatively recent arrival in Morocco, perhaps crossing over from Iberia in historic times.

Radiocarbon dating of the bustard bones—many with signs of juvenile development, indicating year-round hunting—places them squarely within the Late Pleistocene. The birds were not only present but breeding locally, and they appear to have been a familiar part of the landscape and cultural imagination.

“This assemblage confirms that great bustards were a long-term, native part of Morocco’s fauna,” Cooper noted. “They weren’t just hunted. They were known.”

Extinction, Memory, and the Future

Today, the Moroccan population of great bustards numbers fewer than 80 individuals, confined to a tiny range near Tangier. While the birds have survived for millennia, human pressures—habitat loss, hunting, and more recently, collisions with power lines—are pushing them toward disappearance.

Ironically, their oldest known interaction with humans was one of reverence.

“Understanding that these birds held cultural and possibly spiritual meaning for our ancestors might help build modern conservation support,” said Cooper. “They were part of people’s identity, not just their subsistence.”

If early humans could expend energy to transport and prepare these birds for burial feasts, perhaps today’s societies can mobilize to protect the last of them.

Related Research

Munro, N.D. & Grosman, L. (2010).

Early evidence (ca. 12,000 B.P.) for feasting at a burial cave in Israel. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(35), 15362–15366.

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1001809107Alonso, J.C., et al. (2009).

Genetic diversity of the great bustard in Iberia and Morocco: risks from current population fragmentation. Conservation Genetics, 10, 379–390.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10592-008-9580-9Humphrey, L.T., et al. (2012).

Iberomaurusian funerary behaviour: Evidence from Grotte des Pigeons, Taforalt, Morocco. Journal of Human Evolution, 62(2), 261–273.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.11.001

Cooper, J. H., Collar, N. J., Bouzouggar, A., Barton, N., & Humphrey, L. (2025). Late Pleistocene Great Bustards Otis tarda from the Maghreb, eastern Morocco. The Ibis. https://doi.org/10.1111/ibi.13404

Share this post