Tombs Without Thrones

High on the grassy ridgelines of Neolithic Ireland, where fog slips across stone like whispered memory, early farmers raised monuments that still loom over the living. Passage tombs like Newgrange and Knowth, older than the pyramids, have long been cast as the burial vaults of prehistoric kings and queens. But new genetic evidence is unsettling that tale.

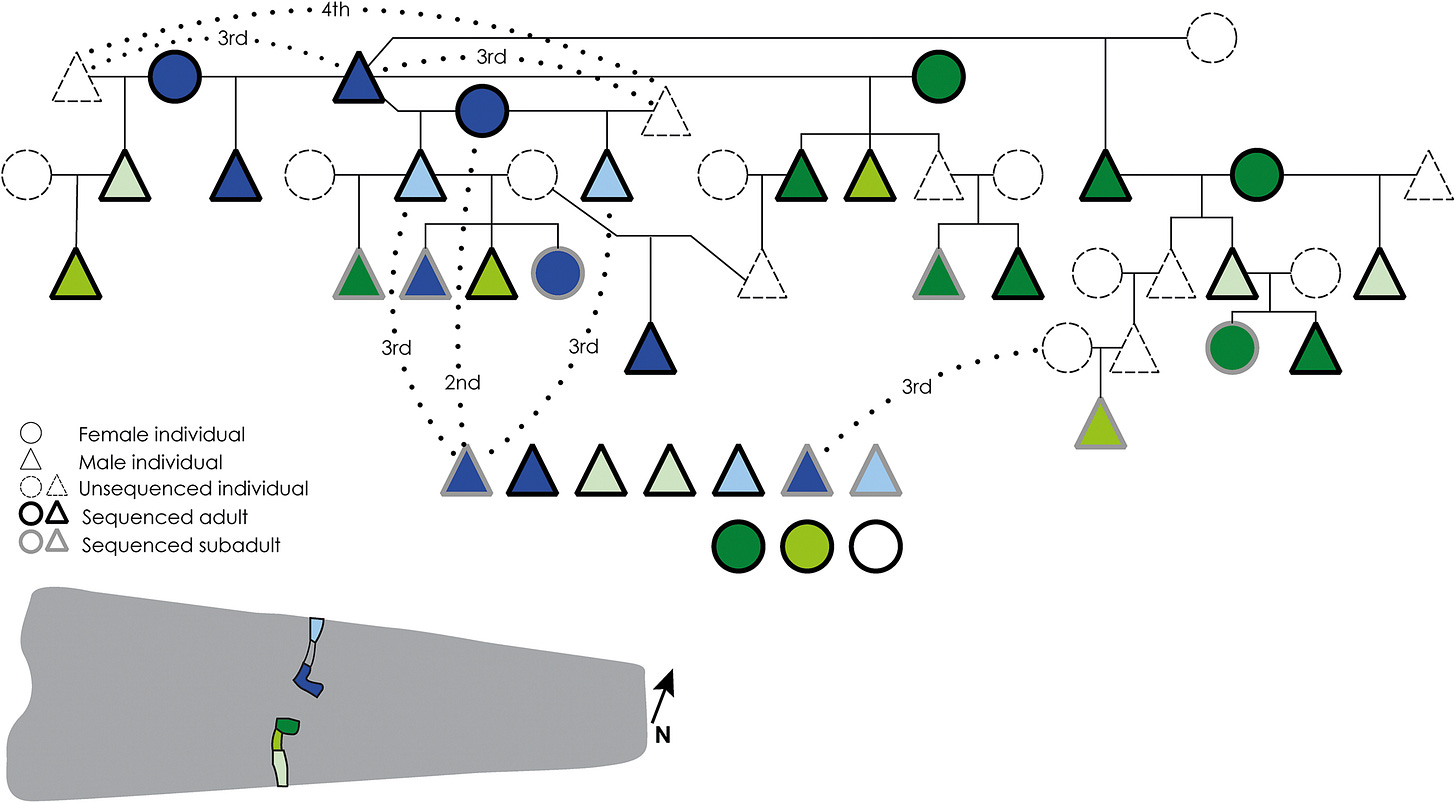

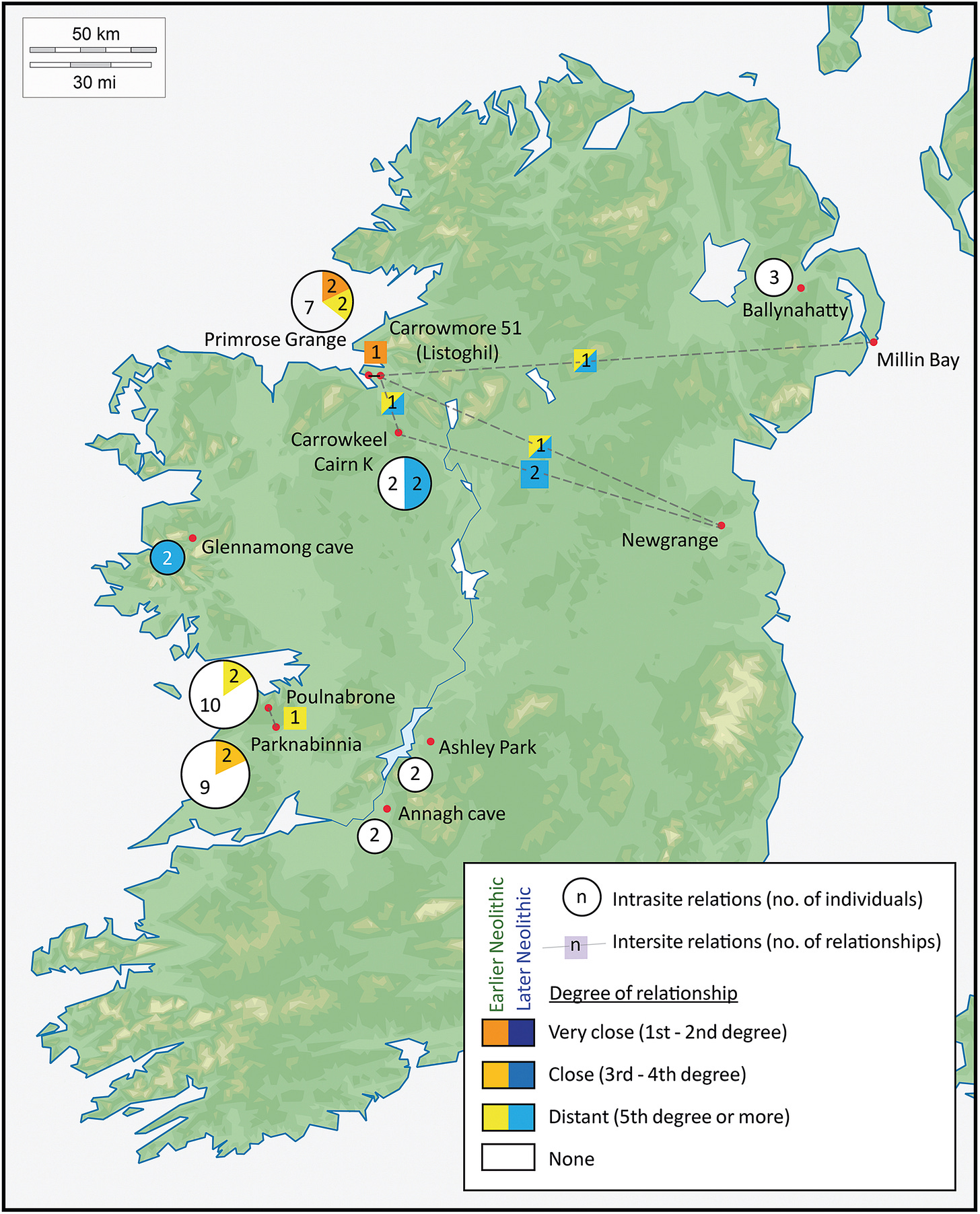

A recent study published in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal1 led by Neil Carlin of University College Dublin peels back the earth not just from bones, but from assumptions. The analysis of ancient DNA from 55 individuals buried across multiple Irish tombs suggests that these were not family mausoleums for ruling elites, as once believed. Instead, they may have been gathering points for scattered communities—communal resting places for a far more complex, cooperative society.

“We cannot say that these tombs were the final resting places of a dynastic lineage who restricted access to ‘burial’ within these tombs to their relatives,” the researchers write.

From Hearth to Monument

The Irish Neolithic (c. 3900–2500 BCE) began with modest tombs—court tombs, portal tombs, and simple stone chambers that mirrored the small, genetically tight-knit communities that built them. But by 3300 BCE, something changed. People began constructing passage tombs: large, carefully engineered burial mounds accessed by stone corridors. These tombs often housed dozens of individuals—and genetic data now suggests they were anything but close family.

Carlin and his colleagues combed through both genetic profiles and archaeological context. They found that while earlier tombs reflect intimate kinship networks, later megalithic monuments show a marked rise in genetic diversity. Few of the buried individuals shared immediate ancestry.

“This reflects how the kin groups using these tombs were interacting on a larger scale and more frequently choosing to have children with others from within these extended communities,” the team concluded.

Rather than entombing their bloodlines, these people were memorializing their collectives.

Rethinking Ritual, Kinship, and Power

Earlier interpretations of Irish passage tombs leaned heavily on hierarchy. Previous DNA work had even proposed elite lineages with incestuous ties, invoking images of Neolithic dynasties. But Carlin’s study reframes these sites not as symbols of dominance, but of diplomacy.

This wasn’t a society where power flowed from blood. It was one where participation mattered more than pedigree. Passage tombs, it seems, became ceremonial gathering places—perhaps visited cyclically for ritual feasts, monument maintenance, and the burial of the recently dead. A sort of sacred commons, where belonging was marked by shared effort, not shared genes.

The idea finds echoes elsewhere in Neolithic Europe. From the Orkney Islands to Brittany, megalithic architecture often suggests collective building, with few signs of hierarchy. The Irish case adds genetic substance to that architectural reading.

“Instead of seeing the Neolithic period as one ruled by powerful dynasties,” Carlin suggests, “we should view it as a more equal society.”

The researchers stop short of calling it egalitarian in the modern sense. But the data strongly suggest that authority—if it existed—was more horizontal than vertical.

After Four Centuries, a Shift

For nearly 400 years, Ireland’s early farmers buried their dead simply. But by the time passage tombs appeared around 3300 BCE, societies had grown in scale and complexity. With this came a shift in how kinship was understood—not just genetically, but socially and politically.

What triggered this change? The study doesn’t pin it to a single cause, but hints at wider transformations: population growth, expanding trade networks, and the forging of new regional identities. Burial, once a private act, became public performance. And tombs became the stage.

“These were times when the past was being materially constructed in stone, in acts of commemoration that helped shape social memory and identity,” the authors write.

DNA, Stone, and What Comes Next

The implications ripple beyond Ireland. For archaeologists, this study is a reminder to reconsider assumptions about ancestry, authority, and architecture. For anthropologists, it’s an invitation to explore how social bonds form and function beyond bloodlines.

As Carlin and colleagues note, more work is needed—new ancient genomes, deeper contextual analysis, and better integration of material culture and biology. But the shift in perspective is already underway.

Neolithic Ireland wasn’t just a land of farmers and tomb builders. It was a place where people reimagined community—where identity may have been measured not by lineage, but by shared lives and collective memory etched in stone.

Further Reading & Related Research

Booth, T. J., & Brück, J. (2020). Death is not the end: Secondary burial in Neolithic Britain. Antiquity, 94(373), 1111–1129. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2020.129

Sánchez-Quinto, F., et al. (2019). Megalithic tombs in western and northern Neolithic Europe were linked to a kindred society. PNAS, 116(19), 9469–9474. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1818037116

Furholt, M. (2021). Mobility and social differentiation in the European Neolithic. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 62, 101294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2021.101294

Skoglund, P., & Mathieson, I. (2018). Ancient genomics and the peopling of the Americas. Science, 362(6419), eaav5447. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aav5447

Carlin, N., Smyth, J., Frieman, C. J., Hofmann, D., Bickle, P., Cleary, K., Greaney, S., & Pope, R. (2025). Social and genetic relations in Neolithic Ireland: Re-evaluating kinship. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0959774325000058

Share this post