The Neolithic Decline: The Role of Ancient Plague in Northern Europe's Population Collapse

New Genetic Evidence Links Early Plague Outbreaks to Demographic Shifts in Prehistoric Scandinavia

A recent study1 has provided new insights into the mysterious population collapse that occurred in Northern Europe over 5,000 years ago. This event, known as the Scandinavian "Neolithic decline," saw the abandonment of large settlements and the cessation of megalith construction. Traditionally, this decline was attributed to agricultural crises, but new genetic analysis suggests another culprit: an early form of plague.

The Enigmatic Neolithic Decline

The Neolithic decline in Scandinavia has puzzled archaeologists for years. The large-scale abandonment of flourishing settlements in prehistory raised questions about the causes of this demographic collapse. Previously, it was assumed that a crisis in early agricultural practices led to this decline. However, this theory lacked concrete evidence, as no clear correlation was found between the decline and climatic changes.

Discovery of Ancient Plague Bacteria

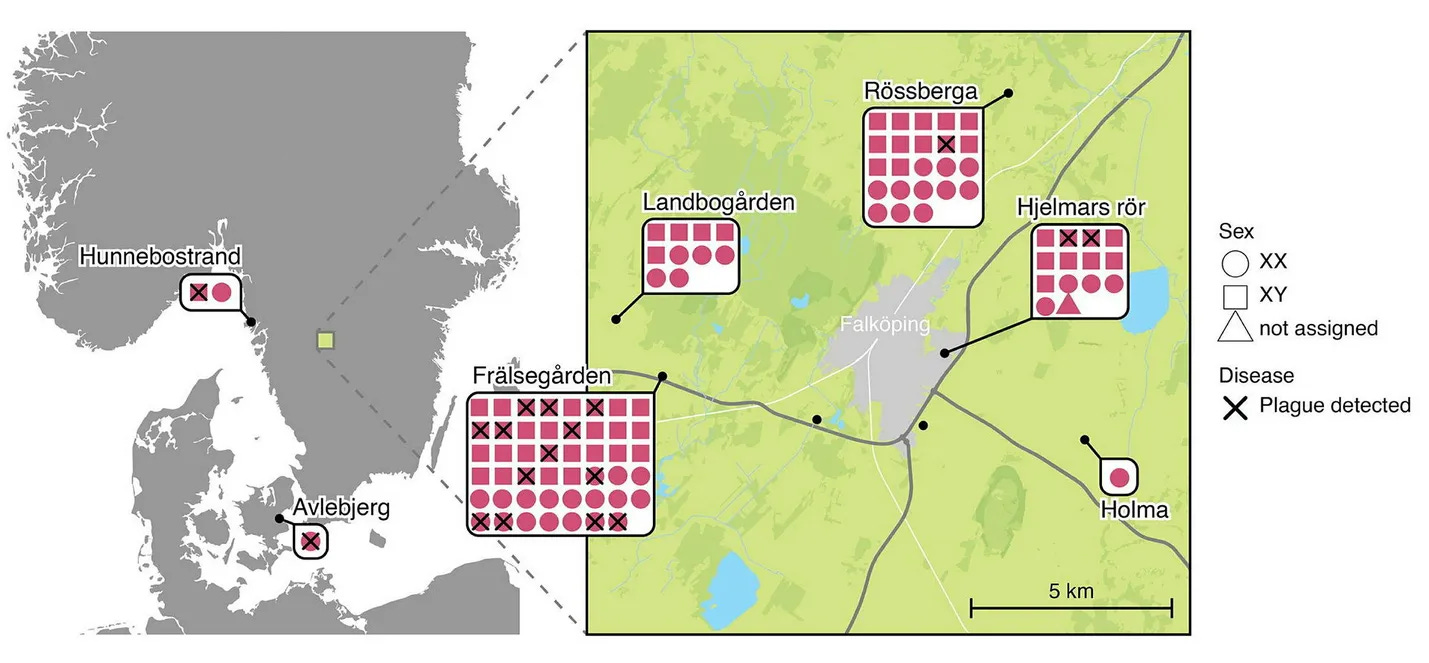

A groundbreaking study published in Nature sheds light on this ancient mystery. Frederik Valeur Seersholm of the University of Copenhagen and his team conducted genetic testing on 108 ancient bodies from eight graves and one stone cist across Neolithic Scandinavia. They discovered an ancestral form of the plague bacterium, Yersinia pestis, in 17% of the tested bodies. This finding suggests that an early form of plague was rampant at the time, potentially contributing to the population collapse.

Prevalence and Impact of the Plague

Although 17% might seem insufficient to cause a population collapse, the study explains that this percentage does not reflect the true prevalence of the disease. The sample only represents those who received ritual burials. Many individuals who died far from settlements or whose remains were not well-preserved may have also succumbed to the plague. Therefore, the actual infection rate could have been much higher, indicating that the plague played a significant role in the Neolithic decline.

The Archaeological Evidence

The theory of the Neolithic decline originated from archaeological evidence showing large-scale abandonment of settlements. Before the downturn, Europe's population was increasing due to the spread of agriculture. The sudden collapse of these burgeoning populations came as a surprise, leading to various theories, including agricultural crises and climatic changes. However, with the discovery of ancient plague bacteria, the disease emerged as a new suspect.

Waves of Plague

The new study suggests that Scandinavia experienced three distinguishable waves of plague during the Neolithic period, spanning about 120 years. The first two waves were relatively minor, similar to the strains found in Latvia and Britain. However, the third wave was more widespread and virulent, possibly acting as the key factor in the Neolithic decline.

Mortuary Practices and Social Structure

The study also shed light on mortuary practices and social structure in prehistoric Scandinavia. By analyzing the burials, the researchers deduced that family members were often buried together, suggesting a patrilineal society where male relatives formed the core. Women were typically buried in different locations, indicating exogamy, or marrying outside their immediate community. This practice likely helped prevent inbreeding, although some evidence of inbreeding was found.

Genetic Insights

The genetic analysis revealed that the majority of the 108 bodies descended from European hunter-gatherers and early farmers from Anatolia. A smaller group featured ancestry from the central Asian steppes. In one tomb, 38 members of a single family spanning six generations were identified, highlighting the importance of family and kinship in Neolithic societies.

Conclusion

This study supports the theory that an ancient form of plague significantly contributed to the Neolithic decline in Northern Europe around 5,000 years ago. The disease likely spread human-to-human, rather than through fleas as in later plagues, indicating that rats cannot be blamed for this ancient epidemic. Additionally, the research provides valuable insights into the social structure and mortuary practices of Neolithic Scandinavia, revealing a complex and interconnected society.

By uncovering these ancient secrets, the study not only deepens our understanding of the Neolithic decline but also highlights the importance of genetic analysis in unraveling the mysteries of human history.

Seersholm, F. V., Sjögren, K.-G., Koelman, J., Blank, M., Svensson, E. M., Staring, J., Fraser, M., Pinotti, T., McColl, H., Gaunitz, C., Ruiz-Bedoya, T., Granehäll, L., Villegas-Ramirez, B., Fischer, A., Price, T. D., Allentoft, M. E., Iversen, A. K. N., Axelsson, T., Ahlström, T., … Sikora, M. (2024). Repeated plague infections across six generations of Neolithic Farmers. Nature, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07651-2