A Jawbone from the Edge of the Map

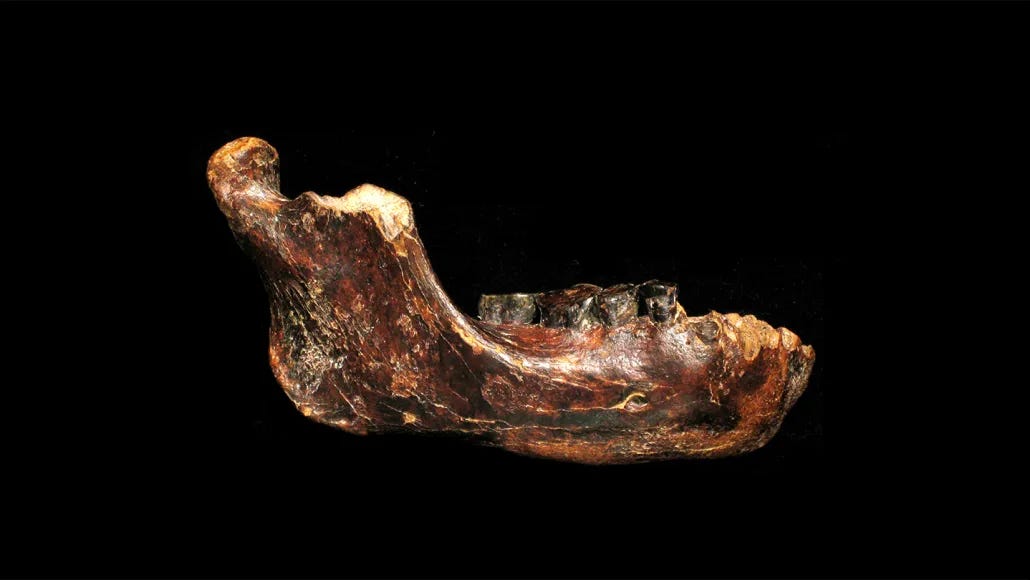

Long before shipping lanes crossed the Taiwan Strait, and long before Taiwan was an island at all, an archaic human jawbone settled into the mud of the ancient seabed. There it rested for tens of thousands of years — until a fishing net hauled it back into daylight.

Today, that jawbone, known as Penghu 11, is reshaping ideas about the Denisovans, a shadowy population of archaic humans whose genetic echoes still linger in modern people across Asia and Oceania.

“Penghu 1 shows Denisovans were not just mountain specialists or cold-adapted northerners,” said Takumi Tsutaya, a biological anthropologist and lead author of the new study. “They lived across a much wider range than anyone expected.”

The Most Elusive of Human Relatives

The Denisovans have always been strange occupants of the human family tree. They were first identified not from their faces or skeletons, but from their DNA — extracted from a finger bone and a few teeth found in Siberia’s Denisova Cave.

It was only later that a few scattered fossils from Tibet and China hinted at what Denisovans might have looked like. Thick-boned jaws. Massive molars. A distinctive anatomy built for endurance.

But until now, the Denisovans seemed a population defined by the mountains and cold — known from Siberia and the Tibetan Plateau.

Then came Penghu 1.

Protein Clues in the Absence of DNA

Pulled from a fishing net and eventually donated to Taiwan’s National Museum of Natural Science, the Penghu 1 jaw retained no usable DNA. But researchers turned to another molecular witness: ancient proteins.

From the tooth enamel of the jaw, scientists extracted over 4,200 protein fragments. Two of those fragments carried distinctive Denisovan signatures — chemical variants rarely seen in humans or Neanderthals.

“Retrieving this kind of molecular evidence from a fossil recovered from the sea floor — that would have been impossible even a decade ago,” noted Sheela Athreya, a paleoanthropologist not involved in the research.

Anatomy that Speaks of Asia, Not Siberia

Alongside the molecular evidence, the physical features of Penghu 1 add to the story. The jaw’s robust structure and the shape of its tooth roots closely resemble a Denisovan jaw from Xiahe, China, discovered high on the Tibetan Plateau.

But Taiwan is 4,000 kilometers from Denisova Cave. Its climate could hardly be more different.

Tsutaya and his colleagues suggest that Denisovans were astonishingly adaptable — capable of thriving in the cold of Siberia, the thin air of Tibet, and the humid lowlands of what is now Taiwan.

“It’s a level of ecological flexibility we don’t often credit archaic humans with having,” Tsutaya said.

How Old is the Jaw? Nobody Knows — Yet.

The fossil defies easy dating. Seawater had long since stripped away its collagen, eliminating possibilities for radiocarbon analysis.

Still, the geography offers clues. During Ice Age glacial periods, sea levels dropped, and Taiwan was connected to mainland Asia. The researchers suggest Penghu 1 likely dates to either 70,000–10,000 years ago, or perhaps an earlier window between 190,000 and 130,000 years ago.

That range overlaps with the known Denisovan timeline — but also leaves room for other possibilities.

A Species or a Population?

The question of who exactly the Denisovans were remains unsettled. Some researchers, including paleoanthropologist Xiujie Wu, propose that fossils like Penghu 1 belong to a distinct species: Homo juluensis. But others urge caution.

“Until we know who the fossils called Denisovans were, we can’t know their fate or their relationship to Homo sapiens,” Athreya cautioned.

For now, Penghu 1 joins a small but growing collection of Denisovan fossils stretching across Asia — from Tibet to Taiwan, from Siberia to the South China Sea.

If Denisovans were as widespread and ecologically versatile as this latest find suggests, the story of human evolution in Asia may be due for a rewrite.

Suggested Related Research

Chen, F., et al. (2019). A late Middle Pleistocene Denisovan mandible from the Tibetan Plateau. Nature, 569, 409–412. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1139-x

Slon, V., et al. (2017). The genome of the offspring of a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father. Nature, 561, 113–116. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0455-x

Massilani, D., et al. (2020). Denisovan ancestry and population history of early East Asians. Science, 370(6516), 579–583. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba0909

Tsutaya, T., Sawafuji, R., Taurozzi, A. J., Fagernäs, Z., Patramanis, I., Troché, G., Mackie, M., Gakuhari, T., Oota, H., Tsai, C.-H., Olsen, J. V., Kaifu, Y., Chang, C.-H., Cappellini, E., & Welker, F. (2025). A male Denisovan mandible from Pleistocene Taiwan. Science (New York, N.Y.), 388(6743), 176–180. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.ads3888

Share this post