Neanderthals are often recognized for their distinct facial features—large, forward-projecting midfaces, prominent brow ridges, and wide nasal openings. In contrast, modern humans have relatively smaller, flatter faces with retracted midfaces and more delicate bone structures. For decades, researchers have debated the evolutionary forces behind these differences.

Was Neanderthal facial anatomy an adaptation to cold climates?

A byproduct of powerful biting forces?

Or was it simply the result of genetic drift?

A recent study published in the Journal of Human Evolution1 examines these questions from a new angle—by tracking how facial growth unfolds from infancy to adulthood in Neanderthals, modern humans (Homo sapiens), and chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus). Using a combination of 3D geometric morphometrics and microscopic bone analysis, the study explores how these species differ not just in their final adult form, but in the developmental pathways that get them there.

How Faces Grow: A Comparative Approach

At birth, Neanderthals already have larger midfaces than modern humans. That gap widens over time, but not in the way many might expect. Instead of growing at a steady rate like humans, Neanderthal midfaces expand dramatically during childhood and adolescence. By contrast, modern human faces reach their adult size much earlier—often by adolescence—before slowing or stopping entirely.

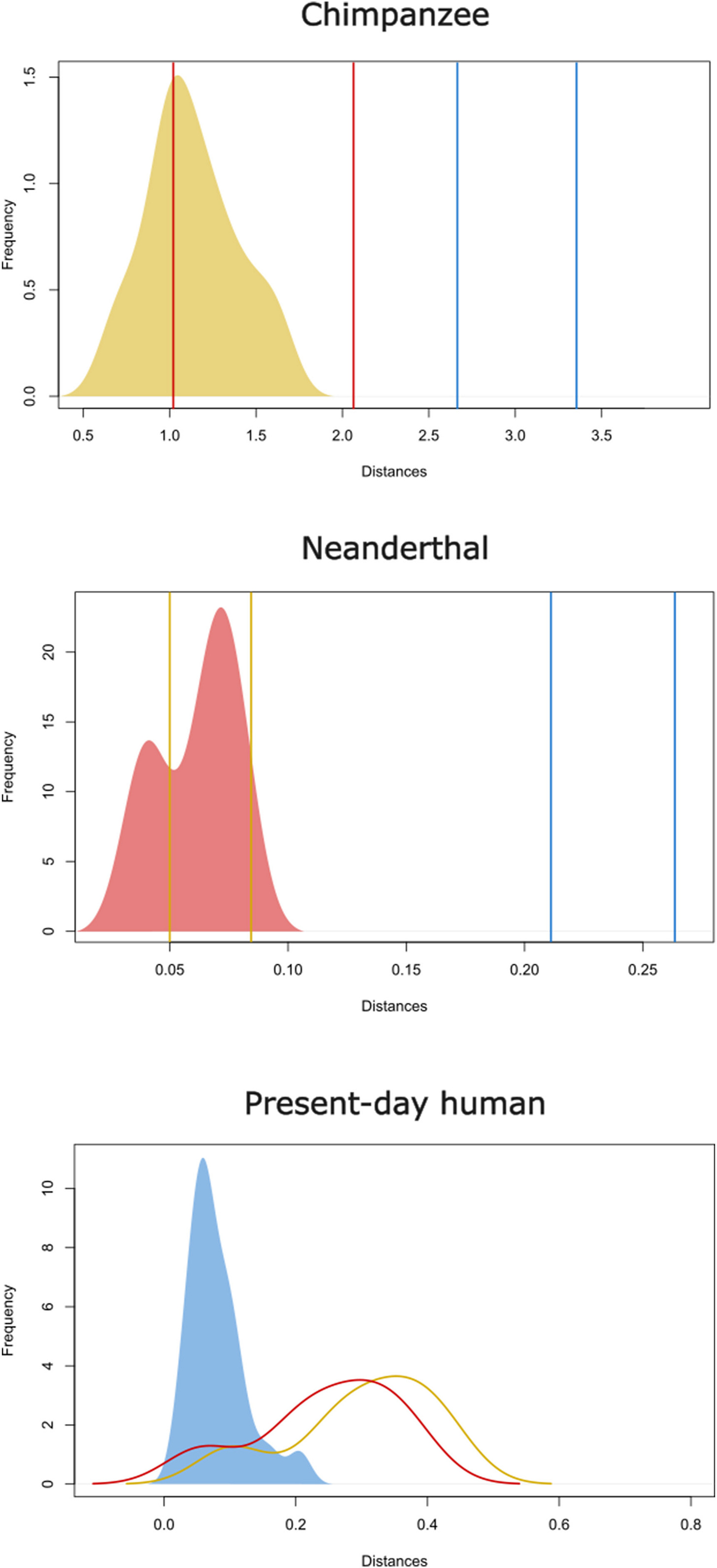

To track these changes, researchers compared skulls from 128 modern humans, 13 Neanderthals, and 33 chimpanzees. Using 3D surface scans and microscopic bone modeling, they analyzed how each species' maxilla—the central bone of the midface—changed shape and size throughout life.

The results show that Neanderthals exhibit prolonged growth compared to modern humans, which contributes to their robust, projecting facial structure. Modern humans, on the other hand, experience earlier cessation of facial growth, contributing to their smaller, flatter midfaces. Chimpanzees, though distinct from both groups, exhibit a growth trajectory more similar to Neanderthals, further supporting the idea that modern human facial development is an evolutionary outlier.

"The midfaces of Neanderthals are on average already larger at birth than those of modern humans and continue growing for a longer period, contributing to their distinctive facial projection," explains lead author Alexandra Schuh of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

Bone Remodeling and Facial Shape

What causes these growth differences? At a microscopic level, bones grow and change shape through a process called remodeling, which involves both bone formation and resorption (the breakdown of bone tissue). The study found that modern humans have higher levels of bone resorption in the midface than Neanderthals, leading to a retracted, flatter facial structure.

Neanderthals, by contrast, show greater bone formation in the nasal and infraorbital regions, which helps maintain their large, projecting midfaces throughout development. In other words, the way bone is added or removed during growth plays a major role in determining the final shape of the face.

"Our findings highlight how the balance between bone formation and resorption shapes the distinct facial morphologies of Neanderthals and modern humans," says co-author Philipp Gunz.

Interestingly, these patterns differ from those seen in chimpanzees. While Neanderthals and modern humans share some similarities in their facial remodeling processes, chimpanzees exhibit distinct bone growth patterns, particularly in the development of their prominent canine region. This suggests that the unique growth trajectory of modern humans is not just an extension of our evolutionary past but a departure from it.

Why Do These Differences Matter?

The distinct facial growth patterns observed in modern humans may be linked to broader evolutionary changes, including shifts in diet, social structure, and even cognition. Some researchers argue that the reduction in facial size and projection in Homo sapiens is connected to changes in dietary habits—particularly the advent of cooking and tool use, which reduced the need for powerful biting and chewing.

Others propose that these facial changes are part of a broader trend toward "self-domestication" in humans—a process in which social selection favors individuals with more juvenile, less aggressive facial traits.

"Facial gracilization in modern humans may be linked to behavioral changes, such as increased social cooperation and reduced aggression," says co-author Sarah Freidline.

Additionally, differences in facial growth could have played a role in speech and communication. Some researchers suggest that the retraction of the modern human midface may have altered vocal tract anatomy, contributing to our ability to produce a wider range of speech sounds.

Neanderthals: A Different Developmental Path

While Neanderthals and modern humans share a common ancestor, their distinct growth trajectories suggest that they evolved along different developmental paths. The prolonged facial growth in Neanderthals may have been an adaptation to high-energy lifestyles, cold climates, or unique social behaviors.

By contrast, the early cessation of facial growth in modern humans may have set the stage for the unique physical and cognitive traits that define our species today.

Final Thoughts

This study sheds light on the fundamental differences in how Neanderthal and modern human faces grow and develop. Rather than focusing solely on their adult differences, it highlights the underlying developmental processes that shaped their evolutionary paths.

Understanding these growth patterns not only helps explain why Neanderthals looked the way they did but also offers insight into the evolutionary forces that shaped our own species. And while Neanderthals may be gone, the echoes of their biology live on in the DNA of modern humans—reminding us that our evolutionary story is still being written.

Related Research

Neanderthal Facial Growth and Adaptation

Bastir, M., & Rosas, A. (2016). Craniofacial levels and the morphological maturation of the human skull. Journal of Anatomy, 228(5), 784-797. https://doi.org/10.1111/joa.12455

The Role of Diet in Human Facial Evolution

Lieberman, D. E. (2008). Speculations about the selective basis for modern human cranial form. Evolutionary Anthropology, 17(1), 55-68. https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.20169

Self-Domestication and Facial Gracilization

Cieri, R. L., et al. (2014). Craniofacial feminization in modern humans: Self-domestication or sexual selection? Current Anthropology, 55(4), 419-443. https://doi.org/10.1086/677209

The Impact of Growth on Craniofacial Form

Ponce de León, M. S., & Zollikofer, C. P. (2001). Neanderthal cranial ontogeny and its implications for late hominid diversity. Nature, 412(6846), 534-538. https://doi.org/10.1038/35087578

Schuh, A., Gunz, P., Villa, C., Maureille, B., Toussaint, M., Abrams, G., Hublin, J.-J., & Freidline, S. E. (2025). Human midfacial growth pattern differs from that of Neanderthals and chimpanzees. Journal of Human Evolution, 202(103667), 103667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2025.103667

Share this post