For decades, archaeologists have puzzled over one of humanity’s most crucial technological leaps—when and how early humans began making sharp stone tools. A new study proposes an unexpected answer: before hominins ever struck two rocks together, they may have been using naturally occurring sharp stones to butcher meat and process plants.

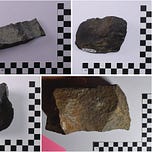

The research, published in Archaeometry1, suggests that before the first intentional toolmakers, hominins may have relied on "naturaliths"—sharp rock fragments created by natural geological or biological processes. These early humans may have used these naturally occurring cutting tools long before they figured out how to produce them deliberately.

“The idea that early hominins just suddenly ‘invented’ knapping as a technological breakthrough doesn’t quite fit,” said Metin I. Eren, co-author of the study and an archaeologist at Kent State University. “There had to be an existing demand for sharp edges before anyone bothered to make them.”

Nature as the First Toolmaker

Stone tool production, or knapping, has long been considered one of the defining skills that set early humans apart from other primates. But Eren and his colleagues suggest that for hundreds of thousands of years before hominins learned to manufacture stone flakes, they simply collected and used ones already lying around. These naturaliths may have been produced in a variety of ways—rockfalls, erosion, wave action, glacial activity, and even trampling by large animals like elephants.

“In some places, nature makes hundreds or even thousands of these naturally sharp stones,” said co-author Michelle R. Bebber, an archaeologist at Kent State University. “Early hominins probably had access to an abundant supply of cutting tools without needing to make them.”

The researchers conducted fieldwork at multiple locations—including Kenya, South Africa, and Antarctica—to document how natural processes produce sharp-edged stones. They found that in many environments, these fragments were not rare at all. Some sites had thousands of sharp stone pieces scattered across the landscape, indistinguishable from early hominin-made tools.

The Missing Link Between Stone and Bone

The study argues that before the first knappers, hominins were already using sharp objects to process food. This likely started with bone flakes created during marrow extraction. Experiments with modern tools suggest that bone fragments can be used effectively to cut meat, but stone flakes are significantly sharper. If hominins were already using bone flakes, it’s not hard to imagine them picking up a naturalith and recognizing its advantage.

“Once you start using sharp-edged materials, you eventually start looking for ways to get more of them,” Eren said. “If you’re in an area with no naturaliths, you have a problem. That’s where knapping becomes useful.”

The researchers suggest that naturaliths served as a bridge between using bone flakes and intentionally striking rocks together to make sharp stone tools. This gradual shift—from opportunistic use to controlled production—may have set the stage for the technological explosion of the Oldowan industry around 2.6 million years ago.

Not a "Eureka!" Moment, But a Slow Discovery

The traditional view of early toolmaking suggests that one particularly clever hominin, perhaps while cracking a nut or smashing a bone, accidentally broke a rock and discovered the sharp edges it produced. But the new hypothesis suggests that knapping wasn’t an accident—it was an imitation of nature.

“Rather than being a sudden breakthrough, early knapping was likely an attempt to copy something that already existed,” said Eren. “Hominins weren’t inventing something new, they were figuring out how to make more of what they already used.”

This changes how archaeologists might interpret the earliest evidence of stone tool use. If early hominins were using naturaliths, then traces of tool use—cut marks on bones, for example—might predate the oldest known knapped tools. Future research will need to look for signs that early hominins collected and carried naturaliths before they mastered making their own.

Implications for Early Human Evolution

If early humans relied on naturaliths before learning to knap, it raises new questions about how our ancestors thought about technology. The ability to recognize and select useful objects in the environment is a key cognitive step in human evolution.

The findings also suggest that archaeologists should reconsider the definition of tool use in the fossil record. If a sharp stone was used by a hominin but not modified, does it still count as a tool?

“If naturaliths were being used extensively, then the history of tool use is likely much older than we think,” Bebber said. “And that means the origins of human technology are more complex than a single moment of invention.”

The Next Steps

To test the hypothesis, archaeologists will need to analyze ancient sites for patterns suggesting naturalith use. This could involve examining sites older than 3.3 million years—the age of the earliest known stone tools—to look for cut marks on bones that may have been made with unmodified rocks. Experimental archaeology could also help determine whether naturally occurring flakes are sharp enough to leave distinct traces that can be identified in the fossil record.

For now, the study challenges long-standing assumptions about the origins of tool use. Rather than a single discovery that launched the Stone Age, early hominins may have been cutting with sharp rocks for millennia before they ever struck two stones together with purpose.

Related Research:

Harmand, S., Lewis, J. E., Feibel, C. S., et al. (2015). 3.3-million-year-old stone tools from Lomekwi 3, West Turkana, Kenya. Nature, 521(7552), 310-315. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14464

Plummer, T. W., Finestone, E. M., et al. (2023). Expanded geographic and taxonomic evidence for early butchery in the Oldowan. Science, 379(6628), 561-566. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adf4234

Key, A. J. M., Lycett, S. J. (2023). The evolution of hominin tool use: A functional perspective on early stone tools. Quaternary Science Reviews, 314, 107963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2023.107963

Eren, M. I., Lycett, S. J., Bebber, M. R., Key, A., Buchanan, B., Finestone, E., Benson, J., Gürbüz, R. B., Cebeiro, A., Garba, R., Grunow, A., Lovejoy, C. O., MacDonald, D., Maletic, E., Miller, G. L., Ortiz, J. D., Paige, J., Pargeter, J., Proffitt, T., … Walker, R. S. (2025). What can lithics tell us about hominin technology’s ‘primordial soup’? An origin of stone knapping via the emulation of Mother Nature. Archaeometry. https://doi.org/10.1111/arcm.13075