A Puzzle in the Permafrost

In the quiet hills near Medzhybizh, a small Ukrainian town nestled along the Southern Bug River, something unexpected has emerged from the deep past: splintered ivory fragments, unmistakably shaped by ancient hands. These are not the ornamental carvings of Ice Age artists. They are tools—fashioned from mammoth tusk, weathered by time, and dating back roughly 400,000 years.

That age alone would be noteworthy. But what sets these artifacts apart is what they reveal: that some of our distant hominin ancestors were not just using stone—they were thinking beyond it.

“What we’re seeing here is early evidence of cognitive flexibility,” said a researcher familiar with the findings.

“These hominins weren’t just surviving. They were choosing, experimenting, maybe even teaching.”

Published in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, the study by Ukrainian archaeologists Vadim Stepanchuk and Oleksandr O. Naumenko pushes back the timeline for intentional ivory working by nearly 300,000 years. The implications are hard to overstate. Until now, the earliest known examples of ivory modification dated to about 120,000 years ago, attributed to Homo sapiens and possibly Neanderthals. This new find opens the possibility that Homo heidelbergensis, or another archaic hominin species, may have pioneered these techniques.

The Site: Medzhibozh A

First identified in 2011 and excavated over several field seasons through 2018, the site known as Medzhibozh A lies within a deeply stratified Pleistocene terrace. Based on a suite of sedimentological and electron spin resonance (ESR) dating, the ivory-bearing layer has been placed within Marine Isotope Stage 11—a warm interglacial period approximately 400,000 years ago.

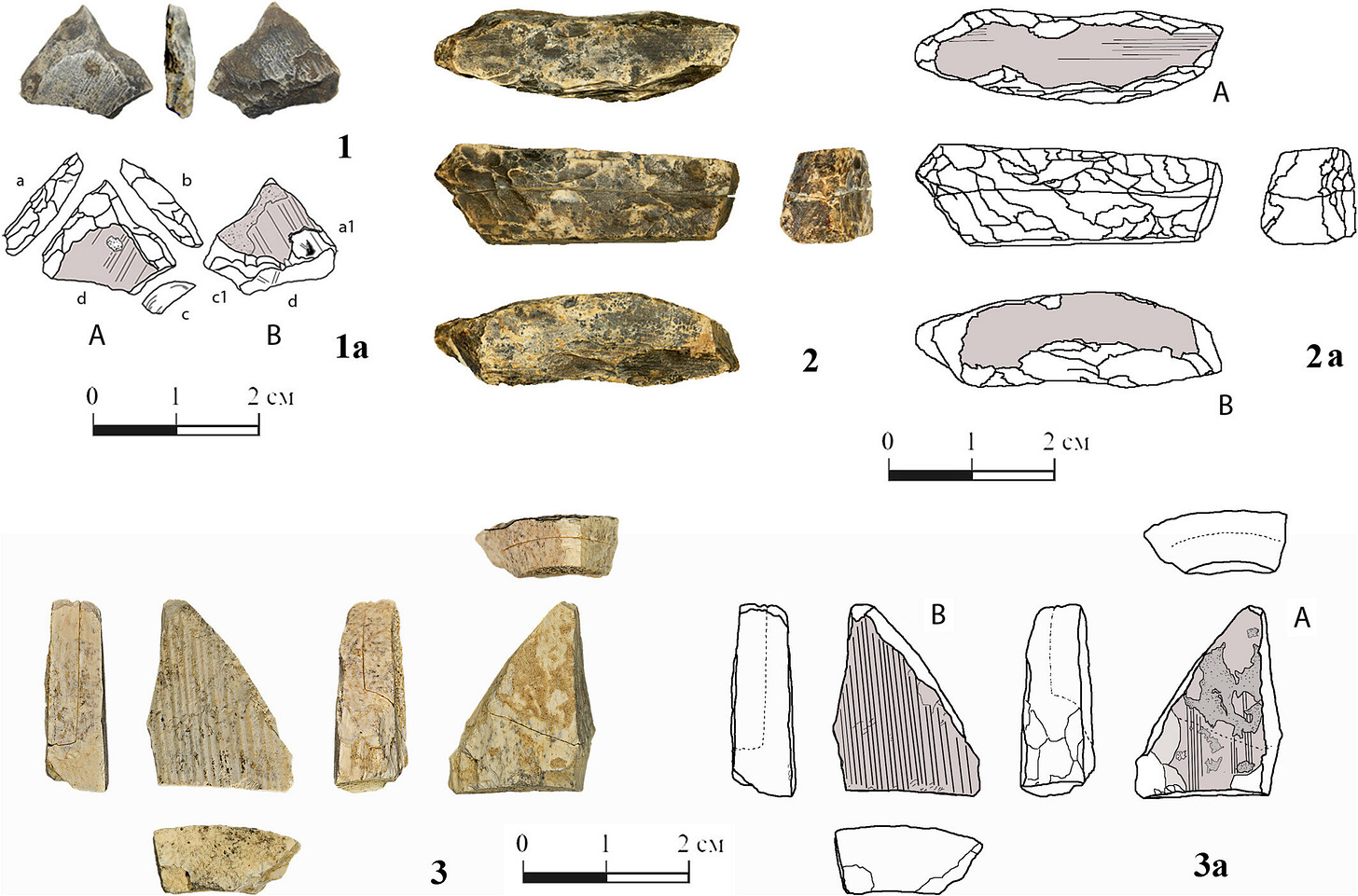

From that ancient layer, archaeologists recovered 24 ivory fragments. Eleven of them bore unmistakable marks of human manipulation: flake scars, trimmed edges, and signs of deliberate shaping using techniques otherwise seen in lithic technology.

One fragment stood out—a pointed implement fashioned with enough precision to suggest a specific, possibly repeated function. Another appeared to be a core, from which other pieces had been struck.

“The presence of bipolar-on-anvil flaking—a technique known from stone tool assemblages—on ivory is especially significant,” said an independent analyst reviewing the material.

“It implies a transfer of learned behaviors across materials.”

Material Matters: Why Ivory?

Ivory is not the easiest material to work with. Unlike stone, it behaves less predictably under force. It splits, splinters, resists control. Which makes its presence here even more intriguing.

Was ivory simply a substitute for stone in a resource-poor landscape? Or was it chosen deliberately for its properties—or even its symbolism?

Stepanchuk and Naumenko propose several scenarios: necessity in an environment lacking quality flint; curiosity-driven experimentation; or pedagogical use in teaching tool-making skills. All suggest a degree of intentionality and foresight.

“What matters isn’t just that they made tools,” one researcher commented,

“but that they chose an unconventional material to do so. That speaks to adaptability—and imagination.”

Beyond Survival: Teaching and Learning?

The notion that these early humans were experimenting with ivory also implies something else: that knowledge was being shared. Skill passed from hand to hand, perhaps from elder to youth.

This may be the earliest archaeological hint of social learning in technological contexts. In other words, these tools could be fossils of ideas—evidence that cognition was moving from instinct to instruction.

“If these were practice pieces, as some suggest, then they are not just tools—they are textbooks,” said one paleoanthropologist not involved in the study.

“That would place culture, in its earliest form, hundreds of thousands of years deeper into our past.”

Interpreting the Evidence

Caution is warranted. Dating can be tricky, especially in open-air sites. Post-depositional processes can move artifacts, and distinguishing deliberate human marks from natural damage is notoriously difficult. But the authors argue that the consistency of the modifications, the presence of multiple flaking techniques, and the recurrence of similar tool forms make a purely natural origin unlikely.

This isn't a one-off anomaly. It appears to be a pattern.

Rethinking the Hominin Mind

What emerges from the Medzhibozh fragments is not just a new archaeological data point—it’s a narrative shift. The stereotypical image of early humans as strictly reactive, opportunistic beings—shaping stone and little else—is giving way to a more dynamic portrait: one of experimentation, abstraction, and cultural transmission.

And all of it was happening long before Homo sapiens walked onto the stage.

Related Research

To better understand the context of these findings, the following studies offer complementary insights into early material culture and cognitive evolution:

Wynn, T., & Coolidge, F. L. (2011). The implications of the working memory model for the evolution of modern cognition. International Journal of Evolutionary Biology.

https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/741357Joordens, J. C. A., et al. (2015). Homo erectus at Trinil on Java used shells for tool production and engraving. Nature, 518, 228–231.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13962Backwell, L., d’Errico, F., & Wadley, L. (2008). Middle Stone Age bone tools from the Howiesons Poort layers, Sibudu Cave, South Africa. Journal of Archaeological Science, 35(6), 1566–1580.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2007.11.006Nowell, A., & Davidson, I. (2010). Stone Tools and the Evolution of Human Cognition. University Press of Colorado.

(Book – no DOI, but widely cited for comparative discussions.

Share this post