Roughly 41,000 years ago, Earth’s magnetic field—our planet’s protective shield—flickered and faltered. The magnetic poles drifted from their usual places, the field weakened to a tenth of its modern strength, and aurorae flared over continents that rarely see them. This episode, known as the Laschamps excursion, did not just create celestial fireworks. According to new research, it may have also reshaped the evolutionary story of humans in Europe and beyond.

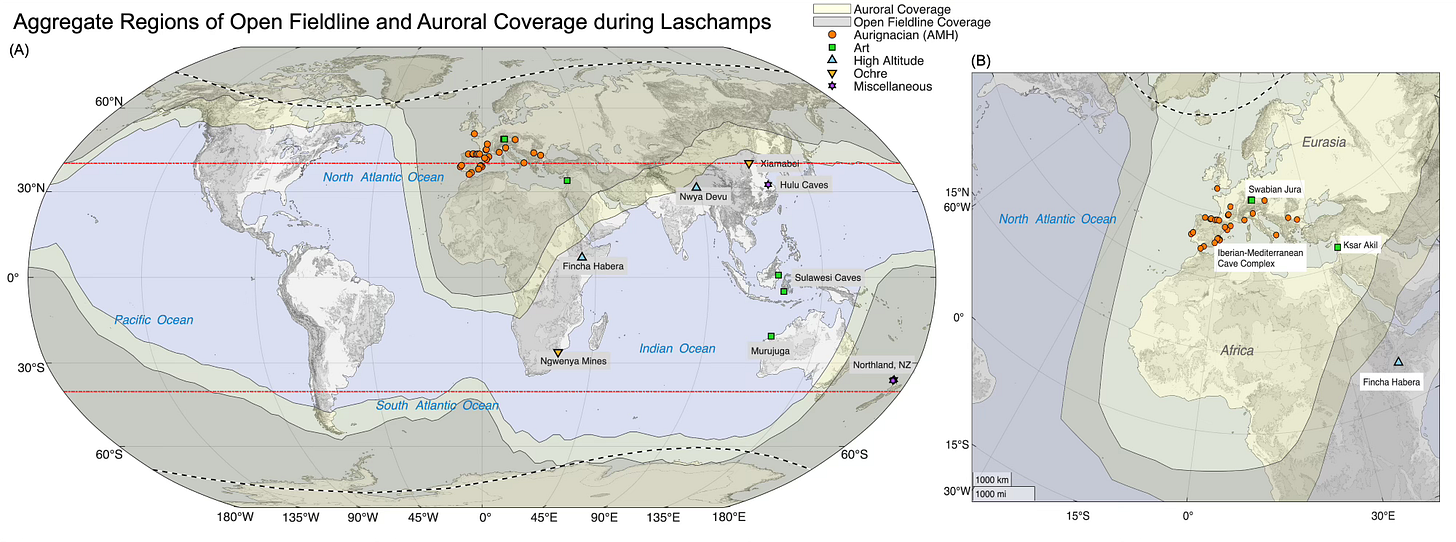

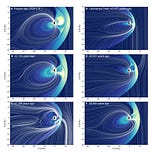

A study1 led by Agnit Mukhopadhyay and colleagues at the University of Michigan has reconstructed Earth’s geospace system during the Laschamps event with unprecedented detail. Their three-dimensional models show a planet bathed in increased ultraviolet and cosmic radiation—especially across Europe and northern Africa—at precisely the moment when Homo sapiens was expanding and Homo neanderthalensis was fading from the archaeological record.

A Planet Under Radiative Siege

The Earth’s magnetic field is more than a compass guide; it is a dynamic structure, sculpted by molten currents in the planet’s outer core. This geomagnetic engine typically keeps high-energy particles from the sun and beyond at bay. But every so often, it stumbles. During the Laschamps excursion, that stumble was dramatic.

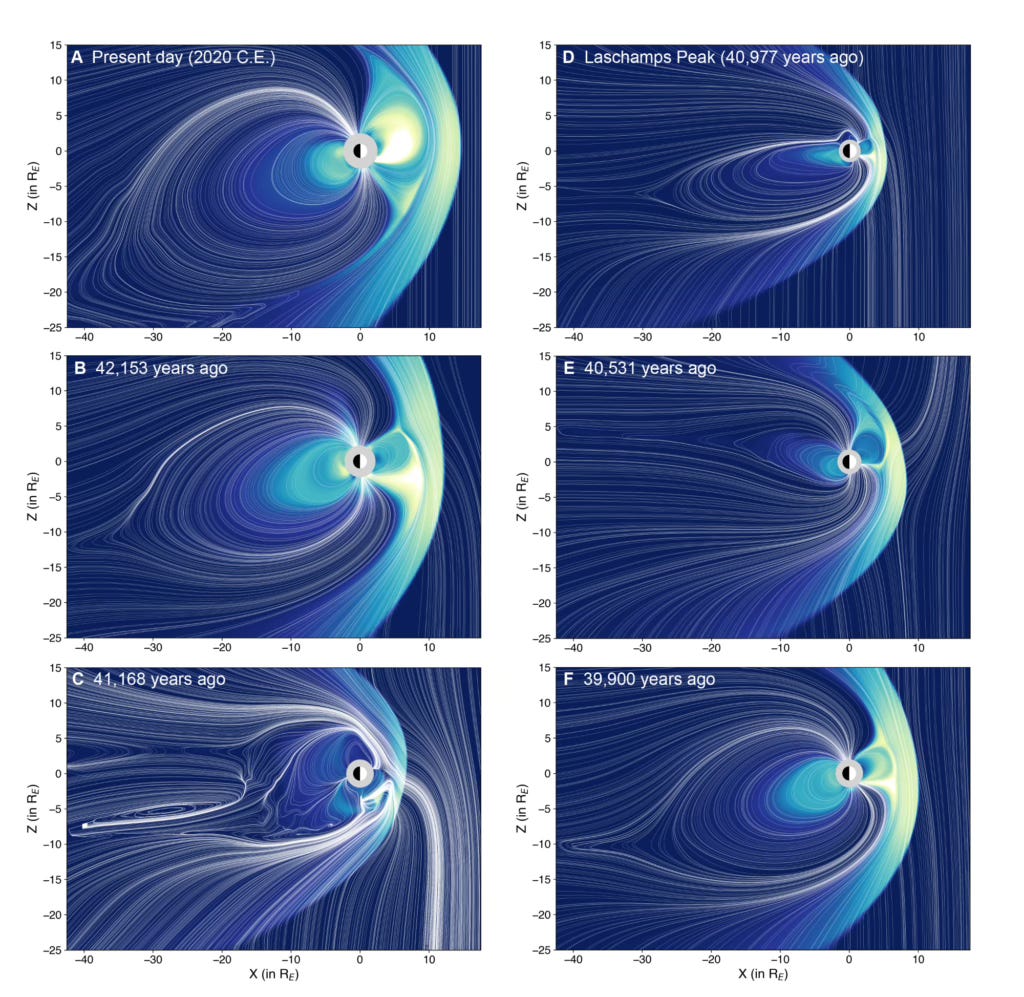

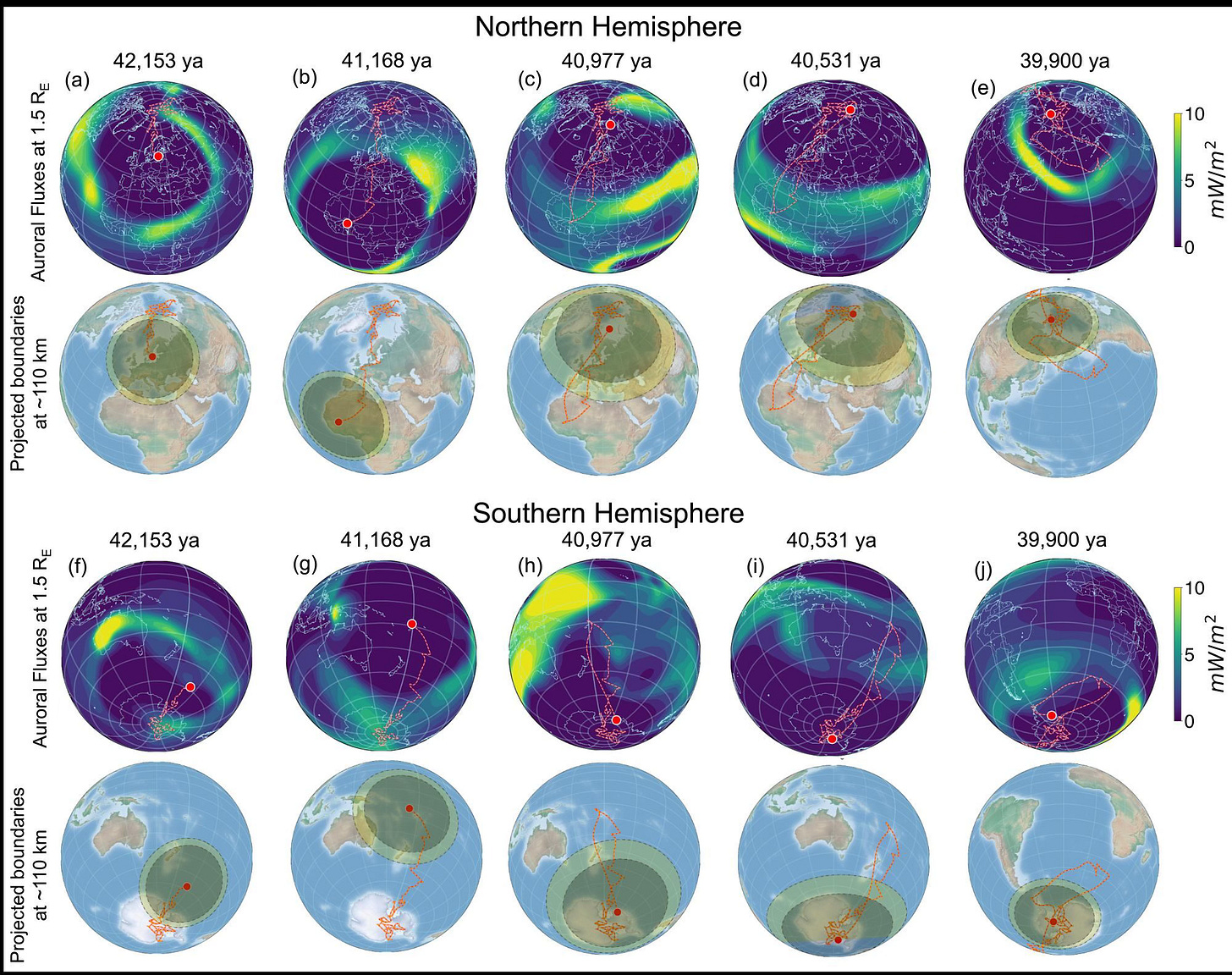

“The field dropped to about 10% of its current strength and the poles tilted more than 75 degrees from their typical positions,” said Mukhopadhyay, whose team modeled the resulting distortions in the magnetosphere and auroral zones.

This collapse caused the auroral oval—the region where solar particles enter the atmosphere and cause polar lights—to balloon in size and drift equatorward. In modern times, auroras flicker over polar skies. During Laschamps, they lit up places like France and the Sahara.

More concerning than the view was the fallout: these auroras marked regions where harmful radiation could reach the ground.

Caves, Clothes, and Ochre: A Human Strategy for Survival

As the magnetic field declined, the effects on Earth’s surface intensified. Ozone depletion, increased ultraviolet radiation (UVR), and heightened cosmic ray exposure would have been especially hazardous to early humans. Ocular damage, folate depletion, and immune suppression are all possible outcomes of such exposure.

Yet archaeological evidence suggests Homo sapiens didn’t just survive this celestial hazard—they adapted. According to co-author Raven Garvey, an anthropologist at the University of Michigan, modern humans likely used a suite of cultural technologies to mitigate UV exposure.

“Tailored clothing, for instance, may have provided both thermal insulation and photoprotection,” Garvey explained. “And ochre, which is frequently found at Aurignacian sites, has demonstrated sunscreen-like properties.”

Unlike Neanderthals, who probably wore simpler, draped garments, Homo sapiens left behind tools such as bone awls and needles—strong indicators of sewn, form-fitting clothing. These innovations would have allowed longer forays away from shelters and greater exposure to irradiated landscapes, without the same risk.

The study also points to a spike in cave use during this period. While caves served many purposes—shelter, ritual, art—they also shielded inhabitants from solar exposure. It is plausible, Garvey noted, that some caves were used not just for their cultural or symbolic significance but as literal refuges from a more dangerous atmosphere.

The Disappearance of Neanderthals, Revisited

Neanderthals had persisted in Europe for hundreds of thousands of years, enduring multiple glacial cycles. But by about 40,000 years ago, they vanish from the fossil record. The timing aligns closely with the Laschamps excursion.

“What distinguished anatomically modern humans from Neanderthals wasn’t just biology, but behavior,” said Mukhopadhyay. “This study suggests that environmental challenges—like a weakened magnetic shield—may have amplified the advantages of innovation and adaptation.”

This is not to say the Laschamps excursion alone caused Neanderthal extinction. Their decline was almost certainly due to multiple factors, including demographic pressures, climatic variability, and competition. But the added stress of global radiation, combined with a lack of protective technologies, may have tipped the scales.

Implications for the Search for Life (and for Our Own Future)

The study’s models don’t just illuminate the past. They also cast a wary eye forward. Earth’s magnetic field is currently weakening at a rate of about 1% every two decades. If another excursion were to occur, the consequences could be catastrophic—not for survival per se, but for technology.

“Satellite systems, communication networks, even air travel would all be at risk during such an event,” said Mukhopadhyay. “But there’s another lesson here, too. Life found a way through one of Earth’s most volatile episodes.”

The research may also inform the search for life on exoplanets. Planets lacking strong magnetic fields are often dismissed as poor candidates for life. But Earth’s own history tells a more nuanced story.

“If early humans could survive an event like Laschamps,” Garvey added, “then life might find a foothold even on worlds where radiation levels are high—given the right behaviors or biotechnologies.”

Further Reading & Related Research

Cooper, A. et al. (2021).

A global environmental crisis 42,000 years ago. Science, 371(6527), 811–818.

https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb8677Nilsson, A. et al. (2022).

Recurrent ancient geomagnetic field anomalies and the South Atlantic Anomaly. PNAS, 119(25), e2200749119.

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2200749119Gao, J. et al. (2022).

Effects of the Laschamps excursion on geomagnetic cutoff rigidities. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 23(10).

https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GC010261Brown, M. et al. (2018).

Earth’s magnetic field is probably not reversing. PNAS, 115(20), 5111–5116.

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1722110115

Agnit Mukhopadhyay et al., Wandering of the auroral oval 41,000 years ago.Sci. Adv.11,eadq7275(2025).DOI:10.1126/sciadv.adq7275

Share this post