The Forgotten Migrant

When thinking about humanity’s migrations across continents, yeast is probably the last traveler that comes to mind. Yet new research led by Jacqueline Peña and her colleagues at the University of Georgia has revealed that wild strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae—the same species that leavens bread and ferments wine—carry silent records of ancient human journeys.

By examining over 300 genomes from yeast living quietly on the bark of oak and other trees, the team found that these seemingly wild populations are anything but untouched by human history. The patterns etched into their DNA trace events that stretch back to the last Ice Age, reflecting the ways humans moved, farmed, traded, and reshaped their environments.

“We are seeing distinct subpopulations within continents,” notes Jacqueline Peña, lead author of the study. “Even though these wild populations appear separate, they're not completely isolated from human activity.”

The study, published in Molecular Ecology1, provides a rare look at how microorganisms have shadowed humanity’s expansion—and sometimes, how they’ve quietly rebelled against it.

A Wild Companion to Civilization

Although domesticated yeast has been shaping bread, beer, and wine since at least 7000 BCE, wild S. cerevisiae continued to live on trees, largely out of sight. Genetically, these forest populations are distinct from their domesticated cousins—but they also show unexpected scars and seams hinting at shared histories.

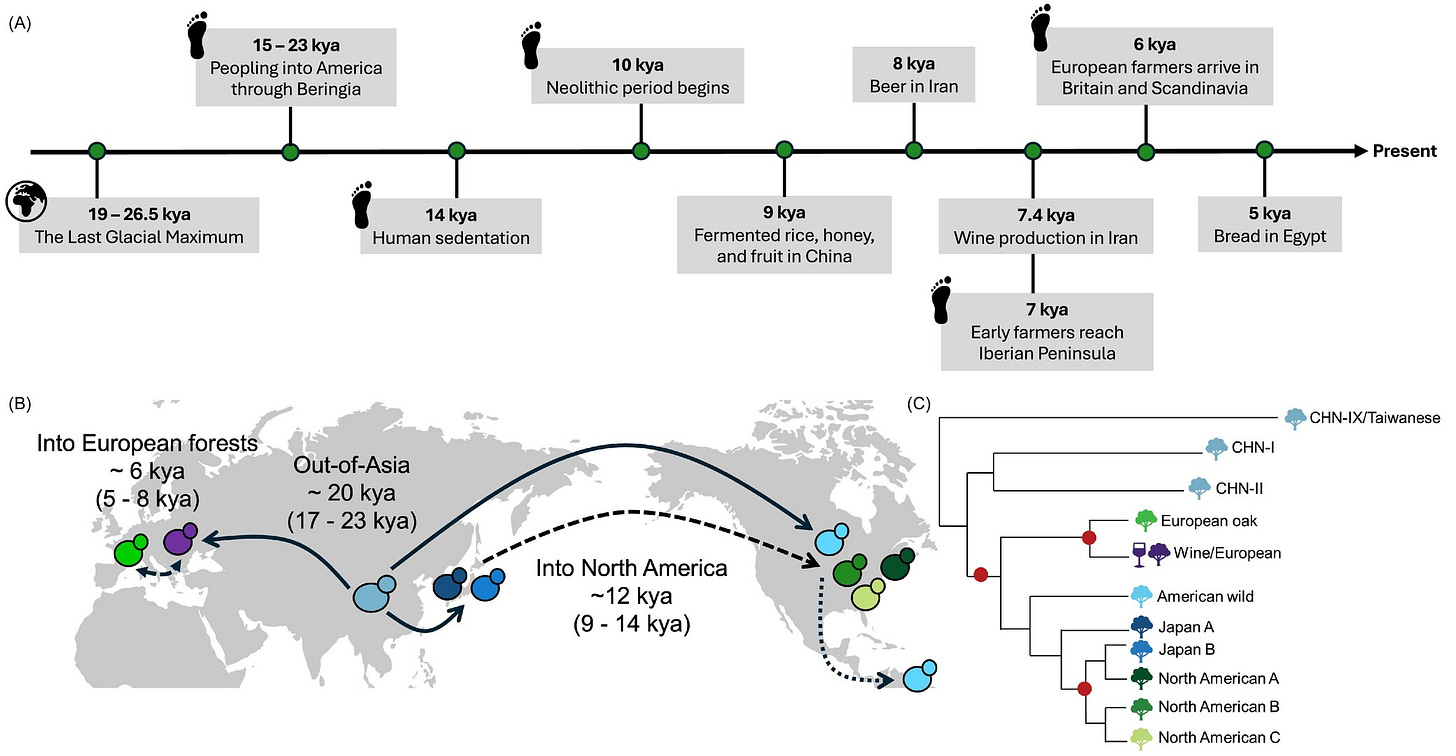

Through extensive genome analysis, researchers found that wild yeast populations in North America, Europe, and Japan likely originated from East Asia, diverging around 20,000 years ago—roughly when ice sheets were retreating and early humans began to domesticate plants.

“Approximate estimates of when forest lineages diverged coincide with the end of the last Ice Age, the spread of agriculture, and the onset of fermentation by humans,” the study explains.

The DNA of these treeside yeasts carries echoes of the very transformations that reshaped human societies.

Migration, Mixing, and the Great Wine Blight

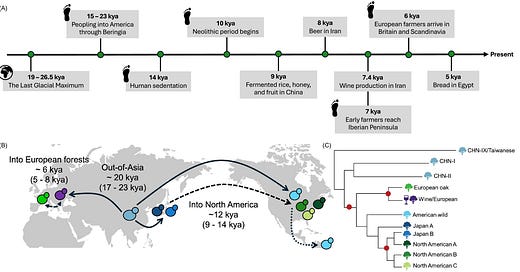

One of the most surprising findings emerged when researchers noticed that yeast strains clinging to trees in southern Europe closely resembled those from the southeastern United States. The genetic link traces back to the 19th century, during the Great French Wine Blight.

When an invasive insect from North America devastated European vineyards, desperate vintners imported resistant grapevines from the American South. Along with the vines came stowaways—wild yeast, unknowingly grafted onto Europe's ancient soil.

“The imported American grapevines could have harbored North American yeast,” the team writes, noting that strains from Portugal and Slovenia now carry telltale genetic fingerprints from across the Atlantic.

In this way, human intervention inadvertently transported not just crops, but entire microbial lineages across oceans.

The Human Footprint in the Microscopic World

The research underscores a subtle but profound truth: even ancient and “wild” ecosystems bear the imprint of human action. Some wild yeast populations show clear signs of intermingling with domesticated strains—likely due to centuries of trade, farming, and migration.

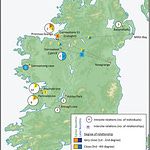

Yet forest-dwelling S. cerevisiae have also maintained strong regional identities. In North America, researchers found several distinct lineages confined to different parts of the eastern United States. In Europe, finer substructures mapped closely to Iberia, Italy, Montenegro, and Greece.

This local diversity suggests that while human influence has been significant, it has not erased the natural evolutionary paths of these populations.

“Forests harbor many isolated yeast populations that are distinct from human-associated lineages,” the authors observe.

Understanding how these microorganisms navigate human-altered environments may offer clues not just to our past, but to how future ecosystems will respond to an increasingly globalized world.

A Microscopic Mirror of Human History

As studies like this deepen, they challenge the neat categories we often use to separate “natural” and “human-influenced” worlds. Just as language, crops, and livestock moved with migrating peoples, so too did tiny, unseen fellow travelers—altering landscapes in ways we are only beginning to recognize.

“If humans, without intending to, were moving microbes around thousands of years ago, just think about all the stuff that we are doing now,” remarks Douda Bensasson, senior author of the study. “We may be changing all kinds of things without knowing it.”

In the grooves of bark and the genetic twists of yeast, the story of humanity unfolds once again—not just in monuments of stone and bone, but in the living, breathing fabric of the forests themselves.

Additional Related Research

Here are some related studies you may want to explore:

Wang, Q.-M., et al. (2012). "Surprisingly diverged populations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in natural environments remote from human activity." Molecular Ecology, 21(22), 5404–5417. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05732.x

Peter, J., et al. (2018). "Genome evolution across 1,011 Saccharomyces cerevisiae isolates." Nature, 556(7701), 339–344. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0030-5

Almeida, P., et al. (2015). "A population genomics insight into the Mediterranean origins of wine yeast domestication." Molecular Ecology, 24(21), 5412–5427. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.13341

Gayevskiy, V., Lee, S., & Goddard, M. R. (2016). "Saccharomyces eubayanus and the origin of lager beer yeast species Saccharomyces pastorianus." FEMS Yeast Research, 16(8). https://doi.org/10.1093/femsyr/fow076

Peña, J. J., Scopel, E. F. C., Ward, A. K., & Bensasson, D. (2025). Footprints of human migration in the population structure of wild baker’s yeast. Molecular Ecology, e17669. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.17669

Share this post